Godforsaken Gulo

Why wolverines need Wilderness.

Somewhere high in the remote Rocky Mountains, an unfortunate mountain goat has been killed by an avalanche. Buried deep in hard-packed snow, its body waits for a lucky scavenger. Only one animal is capable of finding and digging out this mid-winter protein bonanza—Gulo gulo, the wolverine.

This rare and elusive carnivore is the largest terrestrial member of the family Mustelidae, topping out at about 55 pounds of pure muscle and fury. Wolverines are related to badgers, weasels, martens, otters, and mink. In the Lower 48, they are much rarer than any of their cousins, likely numbering fewer than three hundred. These stocky, powerful creatures, armed with strong jaws and stout claws, are capable of amazing feats of climbing, traveling, and crossing snow-covered mountain ranges with ease. One wolverine was tracked climbing Mount Cleveland, Glacier National Park’s highest peak, in 90 minutes, in winter.

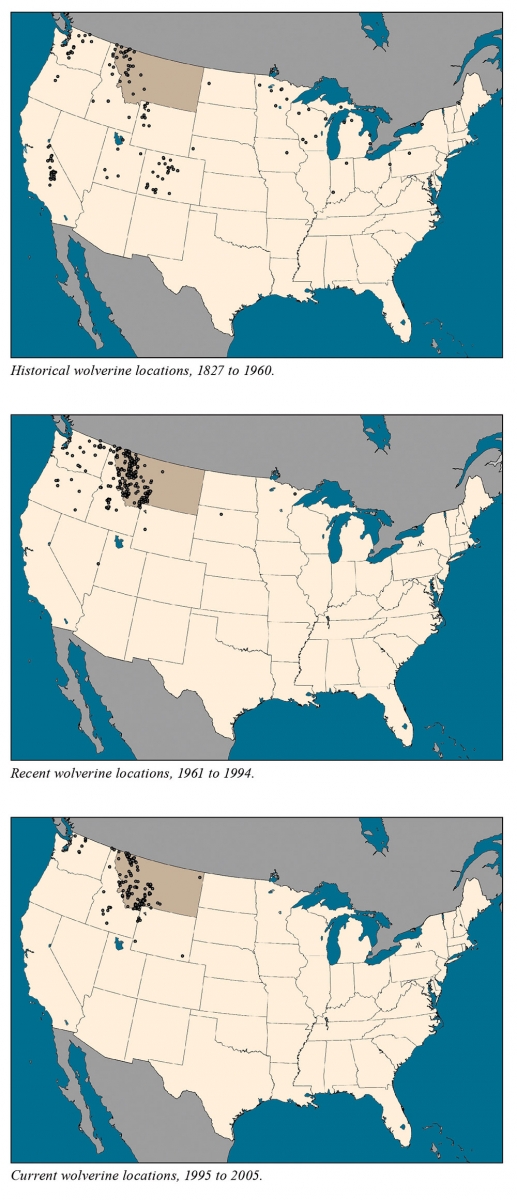

The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) appears dead-set on letting these spectacular creatures go extinct. Driven to minimal numbers by trapping and habitat loss, wolverines were proposed for listing under the Endangered Species Act 20 years ago and still have not received formal protection. The federal government twice issued a “warranted but precluded” decision, meaning the wolverine deserved to be listed—they just didn’t have time to deal with it.

The USFWS did propose to list the animal as Threatened under the ESA in 2013, but withdrew the proposal in 2014 after state governments objected, claiming that climate change is not a threat to the wolverine’s survival. Conservation groups have sued the federal government five times seeking meaningful protection for wolverines. The latest lawsuit, filed in December 2020 by eight conservation groups including Earthjustice, Cottonwood Law, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, and the Center for Biological Diversity, seeks to overturn the 2014 decision to not list the wolverine.

Wolverines seek out the snowiest, most remote habitats, partly for access to tasty frozen entrees like the mountain goat. They also require deep spring snowpack to raise their kits. Wolverine mothers will tunnel deep into the spring snow to create a natal den where their pups are safe, leaving adults free to forage. Deep spring snowpack is diminishing in the Rockies due to warmer winters. This could spell big trouble for remaining wolverine populations.

Remoteness is another quality wolverines crave. Travel into distant cirques by skiers and snowmobilers looking to play may drive a wolverine to take its pups and abandon its den, threatening the entire litter’s survival.

In January 2021, a wolverine was captured on an automatic camera in Yellowstone National Park for the first time. Researchers estimate only seven wolverines roam the vast expanse of Yellowstone. Of course, they also travel into surrounding national forests, where they face a variety of challenges to their survival. Designated Wilderness provides what may be the most secure wolverine habitat outside of national parks, since human access is limited to foot or horse travel.

Listing wolverines as Threatened or Endangered could help protect the remaining populations in Montana, Wyoming, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. Trapping wolverines, part of what led to their near demise, is illegal in the Lower 48, but other threats like habitat loss and climate change remain.

These wily weasels may not be as solitary as once thought. Though males have a large home range—up to 240 square miles—and will mate with several females if possible, some will actually help with raising the pups. Fortunately, wolverines are found all across Canada, Alaska, Scandinavia, and Russia, but their status in many areas is unknown, and in Europe they are considered endangered.

Protecting these honey badgers of the North will require maintaining large areas of remote, wild country, such as the Gallatin Range and the Beartooths, with minimal human disturbance. Wilderness proposals such as the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act and the newly proposed Gallatin Yellowstone Wilderness Act hold promise of setting aside enough undisturbed land to give Gulo gulo a fighting chance.

Species Scrutiny: Wolverines

by Molly Robinson

Subjects of much folklore, wolverines are esteemed and elusive. And while they’re not likely to present themselves at the trailhead, a decent number of these critters call Montana home. So when you’re up in the high country, keep your eyes peeled—for the skunk bear itself, or more likely, sign that it passed through.

Species: Gulo gulo (means “glutton” in Latin)

Closest relative: Weasel

Primary habitat: Cold, snowy landscapes & high-elevation terrain

Primary food: Carrion & small prey

Nicknames: Carcajou, devil bear, quickhatch, devil beast, skunk bear

250-300

Population in Lower 48

Over 50%

Lower 48 population that live in Montana

26-40 pounds

Average weight of adult male

17-26 pounds

Average weight of adult female

3.5-6 inches

Average paw/track size, front to back

200%

Paw expansion when weighted, to aid in over-snow travel

350 square miles

Average range in Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (males)

172 square miles

Average range in Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (females)

2-4

Average size of yearly litter

7-12 years

Average lifespan