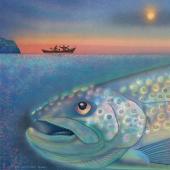

Fishing for Answers

Trout behavior explained.

Ever wonder how trout mange to stay put in the rivers and creeks of southwest Montana during spring runoff? So did I, so I recently sat down with FWP’s regional fisheries manager Travis Horton to find out. What he told me changed my understanding of fish and the complexity of their behavior.

Andrea Jones: What’s happening with fish during winter?

Travis Horton: Like lizards and snakes and other cold-blooded animals, fish body temperatures are dictated by their environment. With ice overhead and colder water, their metabolism slows. With that, they don’t have the same caloric needs as the rest of the year. So, they’re not moving a lot and eating rather passively. You might see most of them hanging out in slower waters and only eating aquatic macroinvertebrates (bugs) that float past their mouth. They probably aren’t chasing food in any way.

AJ: And when the ice starts to break up?

TH: That certainly sets things in motion with many species being spring spawners. Rainbow trout spawning peaks sometime in late March to early April. Arctic grayling start to spawn when valley snow is melting (usually April). And cutthroat spawning peaks at the end of the runoff period in late June to July.

AJ: What about the runoff itself? When it’s super high, why don’t fish get swept away?

TH: Most move to the shoreline out of the main current and wait for things to calm down. At the same time, it’s important to understand that runoff flows serve an important purpose for fish habitat. It’s basically free channel maintenance, depositing fresh gravel, cleaning up silt deposits, and creating places for the fish to deposit their eggs.

AJ: How does that work?

TH: Trout look for pools and riffles with areas of upwelling (or cooler water coming in from underneath the ground). When the time is right, female trout dig their redds (nests) with their tails. Even more fascinating is the fact that trout might travel a couple hundred miles to spawn.

AJ: On that note, you mentioned that people may have misconceptions about fish behavior…

TH: I think it’s a common misperception that fish just randomly swim around in a river, but there’s more to it than that. Fish know their way around a stream like you know how to drive on the street to your house. They have home ranges and they know where they prefer to go. They make complicated spawning migrations and return to the same areas afterwards, often returning to the tributary where they hatched. A lot of times, fish might use olfactory cues to find their way around.

AJ: Fish have noses?

TH: Yes, in a way. Studies have shown that blinded fish could find their way back to where they hatched using just their olfactory senses.

AJ: What’s the general outlook for fry (baby fish)?

TH: It’s a tough go. In rainbows for example, mortality rates from egg to adult is in the 90% range some years. In other words, it takes a lot of eggs to make a fish population. And environmental conditions dictate—through fish growth—to a large degree how many eggs individual trout produce. In terms of egg production, in some smaller streams, which don’t have much food, a single rainbow may reach only a few ounces and produce only 200 eggs. But in a reservoir, which is loaded with food and nutrients, a trout can reach five pounds or more and produce thousands of eggs.

AJ: So there’s more to fish than we thought… rivers too.

TH: Looking down at a stream, everything might look the same, but you get underneath and there are lots of complexities there. Walk a dry stream bed. It’s fascinating. It can help you understand the importance of the bends and the gravel bars, and how they play a part of a fish’s life.

Andrea Jones is the FWP Region 3 Information and Education Program Manager.