Bear in Mind

Understanding pepper spray.

Dr. Chuck Jonkel of the University of Montana had tried everything: flashing projectiles, boat horns, even synthetic skunk spray. Then, in the early 1980s, in a triumphant moment of inspiration that would change the dynamic of human/bear relationships for all time, a clumsy student accidentally shot pepper spray at a captive grizzly. The study found its new focus.

Eventually, graduate student Dr. Carrie Hunt took over the study and began to develop a prototype repellent/deterrent device designed to be portable, inexpensive, and effective. Though it repelled bears 100% of the time and generated no aggressive responses, the spray had considerable disadvantages: it was unpredictable, it required the user to be within six feet of a bear, and its stream was only pencil-thin.

Then, in 1982, Bill Pounds (who would go on to found Counter Assault bear deterrent) contacted Dr. Hunt about her study. He wanted to help by developing a canister with longer spray duration and distance, and a megaphone-shaped cloud to cover a more area. During these studies, the recommendations for bear spray performance standards were set; today the EPA regulates those standards, both for effectiveness and humaneness. After years of work, modern bear spray was born.

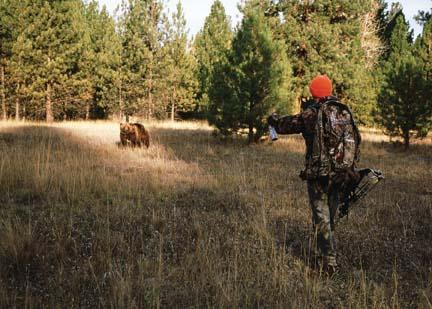

But as the saying goes, “this stuff ain’t brains in a can.” Bear spray should be used as a last resort—without the proper safety techniques to avoid an attack in the first place, you might as well strap a New York strip to your forehead. That’s not to say that bears want to attack you; on the contrary, bears are normally shy and only act aggressively as a last resort.

Bottom line: if you want to live, do your research and don’t be dumb. Here are some FAQs to help you understand that peppery potion.

Q: What exactly is bear spray?

A: The active ingredient in bear spray is capsaicin, an oily substance derived from the same peppers used in spicy foods. When inhaled or touched, it temporarily restricts breathing, causes nausea, tearing, burning, and eye swelling. EPA standards require that the spray contain 1%-2% capsaicin, weigh at least 7.9 ounces, be in a shotgun-cloud pattern, deliver a minimum range of 25 feet, spray for at least six seconds, and be derived from OC.

Q: Is it safe?

A: Yes—it’s EPA-approved to be nonlethal. The effects usually diminish within an hour of contact for both humans and bears, and it causes no permanent damage; plus, the canisters are free of ozone-depleting chemicals. However, people with asthma have a higher risk of death, and repeated use (or misuse) can permanently damage the eyes. If you do come into contact with bear spray, submerge the affected areas in water, relax, and just wait it out—believe me, it’s not gonna be fun.

Q: How do I use it?

A: As with any other weapon, practice makes perfect. First-timers should give it a couple test sprays to practice control; just remember that every test spray reduces that canister’s remaining spray time. Keep it in an easily accessible place, like a chest or hip holster, and keep it next to a flashlight in your tent at night. Use it only as a deterrent, not as a repellent (not as obvious to some as it may seem…), and carefully read the instructions on the canister. Keep an eye on the expiration date, and buy another can right away—better safe than sorry.

There’s a lot more you need to know about bear spray before you’re not dumb. Here are some good resources:

fwp.mt.gov/fishAndWildlife/livingWithWildlife/beBearAware

fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/grizzly/fact_sheets.htm

centerforwildlifeinformation.org

igbconline.org