When Galaxies Collide

The long view in autumn.

The cool, crisp evenings of autumn can be invigorating for stargazing, even if the sky isn’t scattered with bright stars as it will be this winter. There are still distinctive patterns to find, and the fall sky offers an opportunity for the “long view”—all the way to the nearest large galaxy from our own. So grab your binoculars and begin the hunt.

Look up on autumn mid-evenings to find a large square of stars sailing just south of overhead. This pattern forms the front half of the body of Pegasus, the flying horse. Since Pegasus lies upside-down and faces west, the upper-left-hand star of the Great Square, named Alpheratz, marks his belly button. The star, doing double-duty, also marks the head of the constellation Andromeda the princess.

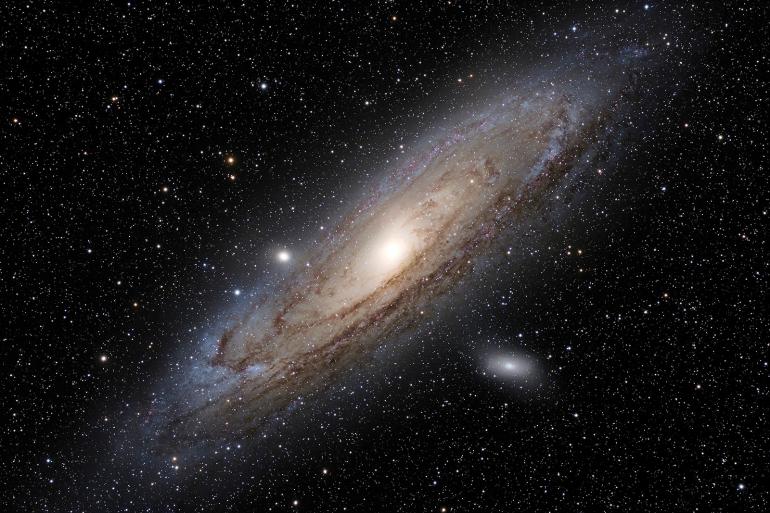

Named for the constellation in whose direction it lies, the Andromeda Galaxy is one of the few galaxies beyond our own that we can see with the naked eye.

Alpheratz marks the tip of the cow-horn pattern forming Andromeda’s body. This star and two of similar brightness make a gently curving string of stars sweeping up and left of the Great Square, marking the lower side of the horn; a curve of fainter stars marks the upper side. Halfway along and just above the upper curve of stars lies an oblong smudge of faint light—readily glimpsed on a clear, moonless night away from city lights. It’s no mere smudge; it’s the Andromeda Galaxy. Binoculars will show it better.

Named for the constellation in whose direction it lies, the Andromeda Galaxy is one of the few galaxies beyond our own that we can see with the naked eye. It’s oblong because its spiral shape, a little bigger than our Milky Way’s, is seen nearly edge-on from our perspective. When past observers began to describe it, they called it the “Little Cloud,” presuming it to be within our own system of stars—which was at the time synonymous with the universe. Its extra-galactic nature began to be suspected—and debated—as early as the 1750s, but was not confirmed until 1925 when Edwin Hubble calculated the distance to certain variable stars in the galaxy, proving it to be a distant and separate “island universe” from our own Milky Way.

And from there, the universe only got bigger.

Current best estimates place the Andromeda Galaxy at about 2.5 million light years away—the farthest we can see something in space with our naked eyes. It also means that when we eyeball it or look at it through binoculars, we’re not seeing it as it is at that moment, but as it was 2.5 million years ago when the light we’re seeing left its stars—back when mammoths and mastodons roamed the Earth.

If our distant descendants are going to witness the galactic mash-up, they’re going to have to do it from a much younger, habitable planet, or a spaceborne colony.

Yet, as vast as our perspective of the universe has become thanks to the investigations of modern science, scientists have calculated that our relationship with the Andromeda Galaxy is going to get a good deal cozier in the future. It turns out that the galaxy is moving toward us, and in four to five billion years, is predicted to collide with the Milky Way. The two galaxies will gravitationally shred each other and combine their stars to form a giant lenticular (disk) galaxy or an elliptical (oval or spherical) galaxy.

What will that mean for Earth? Well, not a lot actually, for by that time, our aging sun will be expanding to its red giant phase, roasting Earth to a lifeless “well-done” status like a burned steak, which the sun will then likely engulf. If our distant descendants are going to witness the galactic mash-up, they’re going to have to do it from a much younger, habitable planet, or a spaceborne colony.

Both of these tumultuous events lie so far in the future that there’s certainly no point in losing any sleep over them. Better to lose sleep by staying up and going out to find the Andromeda Galaxy in the sky while it’s still far away—a smudgy counterpoint to our own Milky Way Galaxy, which wraps its twinkling stars around us on every clear night.

Jim Manning is the former executive director of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. He lives in Bozeman.