Ski Search

My Alpine Education, Part 5: Avalanche Rescue.

Editor’s note: This is part five of a six-part series on learning about avalanches and how to keep oneself—and one’s partners—safe while ski-touring in the backcountry. Read part four here.

After attending a three-day Level 1 avalanche course, the conclusion I came to is this: we can study snowpack, conditions, and weather reports until we’re blue in the face, but knowing how to perform a proper rescue can really only come from practice in the field. So I signed up for a companion rescue course put on by Friends of the Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center. The course lasts two days and consists of an indoor classroom session followed by an outdoor field session. It’s designed to familiarize attendees with rescue gear, techniques, and first aid.

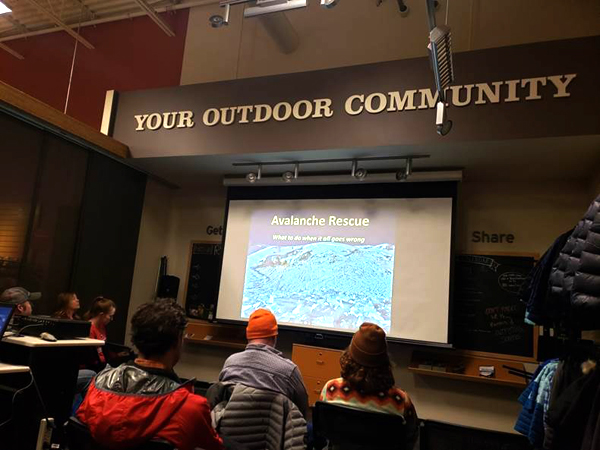

REI hosted the classroom session, where the first topic was gear. What to keep in our packs ranged from the basics—beacon, shovel, probe—to extras such as snow saw, inclinometer, compass, firestarter, a way to boil water, and extra layers. Where you’re headed determines how many extras you need. During this discussion, many folks wondered about the efficacy of airbag packs, which increase a person’s overall size, thus increasing the chances of staying afloat during an avalanche. The instructor said the packs can be great tools, depending on the circumstances, but the number-one reason they fail is user error. Bottom line: our gear does nothing for us if we don’t know how to use it.

Next, we watched videos of live avalanche-rescue situations and evaluated what went wrong and what went right. A few of the slides resulted in fatalities and took place right here in southwest Montana—it hit close to home. Improper rescue protocol was common in the videos: the skiers or snowmobilers were either traveling with inadequate gear or didn’t execute a rescue quickly enough to save their companions. But the most common mistake was “beacon tunnel-vision,” which I would experience during the field session the next day. I’d be very thankful I made the mistake during a practice scenario and not in real life.

The next morning I left my house early and drove up the snow-packed road to History Rock in Hyalite Canyon. The first thing we did was a beacon check. We ran up and down, back and forth, and side to side in the parking lot, watching the arrows and numbers on our beacons. Then we searched for two "victims" buried deep in a parking-lot snowbank. Digging into the side of a plowed-up snowbank pretty accurately replicates the challenge of avalanche debris: it’s clumpy and full of ice chunks that can be hard to move around.

After a couple hours, we moved out into the field and ran several scenarios. With each one, I became more familiar and efficient with my gear. Every time I dove into my backpack to break out my shovel and probe, I fumbled around a little less and got a little faster. Single-burial searches became a breeze, but multiple-burial searches were much more complicated and took constant communication and organization among searchers. Multiple-burial searches are the most critical to practice in advance. Each scenario is different and no one can predict exactly how it will unravel; but the more you practice, the more confident you’ll be in a real situation.

During the last scenario of the day, I was feeling confident and in-tune with my gear. I started my beacon search. I zigzagged across the field, and soon my beacon was within five meters. Only then did I look up to see gloves, poles, and a backpack strap sticking up out of the snow—I had forgotten to do a visual search before diving into my beacon search. As I wound my way across the field focused on my device, I missed the bigger picture, and I committed the most common avalanche-rescue offense: beacon tunnel-vision. If I had looked up and done a proper visual search, I would have completed the rescue much more quickly. Luckily, it was just practice.

As William Butler Yeats said, "Education is not the filling of a pail, but the lighting of a fire." After spending so much time practicing and still making mistakes, I understand how important it is to keep learning and keep training. The fire has been lit.

Next up in the series: after putting her newfound knowledge and experience to use in the mountains, the author reflects on her avalanche education and how it has informed her attitude and conduct while touring the backcountry.