Looking for Ghosts

A weekend road-trip to southwest Montana’s abandoned boom towns.

Not being a bow-hunter, my schedule in the early fall is typically wide open—open as the prairies of eastern Montana. So, rather than twiddling my thumbs until rifle season, I and my girlfriend decided to visit several Montana state parks we hadn’t seen before. Given the time of year and impending holiday season, our destination of choice should come as no surprise. It was time to roll back the clock. We were looking for ghosts.

The plan was simple. Montana’s three premier ghost towns—Bannack, Elkhorn, and Granite—can all be visited in the span of one weekend, so why not visit them all? The route connecting them doesn’t exactly create a perfect loop, but a little backtracking never hurts, and the country connecting them is gorgeous.

Friday was a blur (as most Fridays are, especially before a highly anticipated weekend). As soon as the clock struck five, I sped over to Maggie’s house. She was waiting in the driveway, a big grin on her face. It’d been a hectic summer—much too full of work, deadlines, and entertaining visiting family—and a weekend away was a welcome change. We loaded our bikes and set out for Bannack State Park. Following a friend’s advice, we took the scenic route, passing through Butte before exiting at I-15 to drive along the Big Hole River.

Finding camping on-site was a breeze, as tourist season was behind us. Though staying in a teepee would’ve been neat, the bed of the truck would have to do. We prepared the last of my antelope brats on the tailgate before settling in, knowing we’d need a full night’s rest for the long day ahead. We woke to the sound of birdsong just as the sun began to crest above the Pioneer Mountains and set off to explore the once-bustling mining town of Bannack.

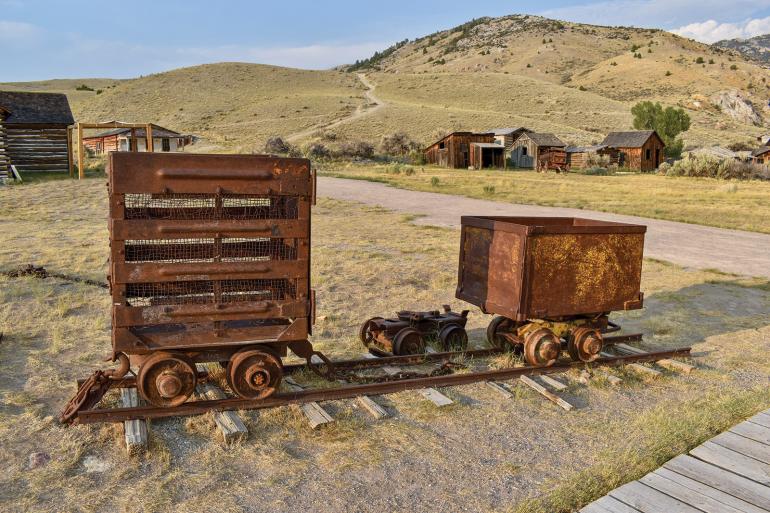

Bannack was the largest town we’d visit on our trek, with over 60 original buildings constructed of weathered timber and stone. It’s a time portal back to the Old West.

Strangely enough, I’d never been to Bannack, as my fourth-grade trip was cancelled due to torrential rain. But the significance of Montana’s first territorial capital would likely have been lost on my ten-year-old self anyway. Being a history buff—and a near history major in college—it was difficult not to feel foolish, having long believed Virginia City to have been Montana’s original boomtown.

We walked along the wooden boardwalks, entered and investigated the now-abandoned taverns, banks, and shops, and solemnly observed the West’s traditional bulwark against bad behavior—the gallows, where Montana’s most (in)famous lawman and outlaw, Henry Plummer, met his end. Bannack was the largest town we’d visit on our trek, with over 60 original buildings constructed of weathered timber and brick. It’s a time portal back to the Old West, so much so that we felt somewhat out of place dressed in our Gore-Tex jackets and sneakers.

Once we’d gotten our fill, we hustled back to the truck and hit the road, as time was of the essence. We pointed the wheels northward and made haste to Philipsburg. Being rather thirsty upon our arrival, we stopped by the brewery for a quick lunch and cold libations. Once the tab was paid, we drove up the treacherous road to Granite Ghost Town State Park.

Unlike Bannack, much of what remains of Granite is in various states of disrepair, and some in absolute ruins—piles of timber, brick, and stone, collapsed after years of neglect and abandonment.

Thankfully, we didn’t encounter any other motorists on our way up the hill, allowing us to stay comfortably in the middle of the one-and-a-half lane road. In typical western fashion, Granite had once been home to 18 saloons & bars to quench the thirst of its 3,000 residents. The population shrank to a scant 140 within a year following the repeal of the Sherman Purchase Silver Act in 1893, which slashed the price of silver and forced most to desert the town. Unlike Bannack, much of what remains of Granite is in various states of disrepair, and some in absolute ruins—piles of timber, brick, and stone, collapsed after years of neglect and abandonment. Fully intact, however, is the Superintendent’s House, which is maintained by the state.

From the forested streets, we could see across the mountains to Discovery Bike Park—our next stop come morning. But light was fading fast, so again we hustled back to the truck and made our way down the mountain and over to our campsite alongside Flint Creek. We nestled into our sleeping bags and turned on our headlamps, hoping to do some reading before bed. But it had been such a long day that sleep came almost instantly.

The drive from our site to Georgetown Lake was stunning, with the brilliant orange of the rising sun painting each side of the winding mountain pass. We walked the shore for a couple hours, took a hasty “shower,” and enjoyed our coffee before meandering over to Disco. We unpacked our bikes and set about on a thrilling morning of lift-accessed downhill riding. After several hours, we’d had our fill, at which point it was time to make our way to our final stop: Elkhorn State Park, the least ghastly of all the ghost towns we were to encounter, which, as of 2020, still boasts a whopping 12 residents.

I appreciated the diminutive size of Elkhorn State Park, as it allowed me to read each plaque, speculate on the history, and more carefully explore the well-preserved Fraternity & Gillian halls.

Elkhorn is the smallest state park in Montana, as only two buildings—Fraternity Hall and Gillian Hall—are preserved and maintained by the state. (The rest of the town is privately owned.) Like Granite, Elkhorn was once a bustling silver-mining community with a peak population of 2,500 residents, though the repeal of the Sherman Act—coupled with a diphtheria epidemic and halted railroad service—greatly diminished the population. While there was less to observe and explore compared to Bannack and Granite, it was nonetheless an interesting place, especially since a handful of folks still live there. In an odd sense, I appreciated the diminutive size of the park, as it allowed me to read each plaque, speculate on the history, and more carefully explore the well-preserved Fraternity & Gillian halls—the former being the host of several fraternal organizations, as well as prize fights, dances, theater productions, and social gatherings.

Having exhausted all the opportunities in Elkhorn, Maggie and I reluctantly loaded ourselves into the truck and headed for home. It had been a weekend for the books, and one that truly impressed each of us. Once again, Montana’s State Parks and the Montana State Park Foundation had provided us with the fodder for a fantastic road-trip and an excuse to explore more of what our great state has to offer. It was a lot of driving, but I’ll take that over sitting around waiting for elk season, any day of the week.