Paradise Watched

First light in the Paradise Valley.

This early in the day, the road is home only to the deer, the antelope, and me. In the dim, dewy calm, they graze along the cutbanks and sandbars of the Yellowstone River under the attentive eyes of red-tailed hawks perched on fenceposts along the road. As my truck lumbers by, they raise their delicate heads and run, bounding through the lush grasses and rich, muddy meanders that led settlers to call this place Paradise Valley.

I have watched this valley and its mountains change, day by day, dawn by dawn for months now. Rising before light, driving my route from Livingston to Gardiner, throughout Yellowstone Park and back home, I have seen the shifting seasons and the fickle moods of a place bigger than time.

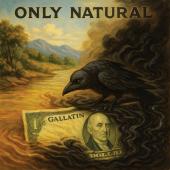

I watch these changes from behind the two-inch-thick windshield of an armored truck. My job is to collect and protect the wealth of Yellowstone National Park. But these quiet mornings beneath the summits yet striped with snow—Black Mountain, Mount Cowen, Emigrant and Electric Peak—are more than passing scenery. They connect me with the place I am fortunate to call home.

From the black mornings of May, when snow spits across the windshield and headlights struggle to pierce the thick, lingering night, to the sweltering furnace blast of August, when RVs and drift boats clog the road, and dust rises from distant lanes to mix with the smoky tangerine dawn, my mornings melt together like the pages of a flip book. The same drive. The same valley. The same deer and antelope and hawks. But it’s never the same.

In the early months, the road is empty and gray. Ranchers' pickups, splattered with mud and manure and bits of grass and hay contrast sharply against the immaculate foreign SUVs of the privileged new generation of Paradise Valley settler. The mountains lie quietly buried beneath winter’s snow; smooth and clean and bright against the dark thunderheads of spring. In the valley, still speckled with dirty drifts, wide-eyed calves buck alongside small herds of white-tailed deer grazing belly-deep in aromatic pastures.

Week by week, the mountains streak with ocher and brown, and so too does the river, running high and fast and murky. It carries entire trees down its channel, entire fences and sheds and cars and dead animals and a world of debris unknown to all but the current. The Yellowstone has run this way forever, a wild river as there ever was, a slave only to the earthly sirens of snow and rain and sun.

The tourists have not yet arrived, for this is not the Montana advertised in movies or on postcards or in glossy magazines. This turbid river, these ragged mountains, the valley heavy with the damp scents of life and death and dirt, it’s all shown to me in bits and pieces each morning as I pass. My picture of the whole becomes clearer.

It’s strange, some days, to look through the windshield, through the empty coffee cups and greasy food wrappers and dented aluminum clipboards wedged on the dash, at the land and the river and sky. I sit in my climate-controlled, bullet-proof box day after day, still and silent, watching as the world changes all around, always moving, but never going anywhere.

Then one day summer arrives. The Yellowstone sinks comfortably below its banks, running clear and lazy once more, and the insects—mayflies, stoneflies, caddis, and eventually hoppers—hatch. They fill the air so thickly that the windshield of my truck becomes opaque with carnage. An organic macramé of legs and wings and thoraxes and gore plasters the grille and clogs the air filter and streaks the fenders with unlikely color. And following the hatch, in similarly sudden fashion, come the tourists.

The sticky-hot mornings are no longer shared with the deer and the antelope. They disappear into the cottonwoods and canyons as the road swells with traffic. Eager fishermen and photographers vie for first light and first bite, and the lanes constrict under a tide of out-of-state license plates towing campers and boats and motorcycles. They pass me on the dotted lines, always in a hurry to get somewhere else, and I wonder if they see these mornings as I do. For all of their looking, do they see this place at all?

But like the river’s current, this outpouring, too, will diminish. The days will grow shorter. The dawn air will begin to bite with a familiar chill, and the mountains will again be dusted with white. The deer and the antelope will return, under the watchful eye of the red tailed hawk. The road will empty, and I will rise each day to drive and watch and wonder once more.