Headwaters History

Exploring the past of our meandering rivers.

The Missouri Headwaters, a lush and beautiful area lying on the northern edge of a vast, mountain-rimmed basin, is one of the key sites in western history, particularly in the fields of Indian intertribal relations, exploration, and the fur trade. Notable figures who were prominently associated with the place include Lewis, Clark, Sacagawea, John Colter, George Drouillard, and Cols. Pierre Menard and Andrew Henry. At this “essential point in the geography of this western part of the continent,” as Lewis termed it, the Gallatin flows into the Missouri approximately half a mile northeast of the Jefferson-Madison confluence.

Lewis and Clark, the first documented white men to visit the locale, found it teeming with wildlife. For this reason, it was a meeting place and disputed hunting ground—often a dark and bloody no-man’s land—for various Indian tribes. In this region, the Blackfeet and Minitaris raided the Shoshonis and Flatheads when they ventured eastward over the mountains to hunt. In fact, Sacagawea’s village of Shoshonis camped at the same place as the expedition, near the confluence of the Jefferson and Madison, about five years earlier when she was about 12 years old. The Minitaris attacked the village and captured her about four miles farther up the Jefferson.

The Lewis & Clark Expedition, eagerly seeking the Shoshonis, who could help in crossing the mountains to the west, arrived at Three Forks not long after completing the arduous portage of the Great Falls of the Missouri. Clark and an advance element of four men reached the forks on July 25, 1805, and explored the lower 32 and 20 miles, respectively, of the Jefferson and Madison. The boat party made its appearance two days later, set up a base camp on the south bank of the Jefferson a short distance from its juncture with the Madison, and reunited with the Clark group. The next day, some men probed a ways up the Gallatin. Nursing the ailing Clark and trying to decide which of the three streams led westward, the expedition stayed at the forks until July 30. A crucial decision was easily reached to follow the Jefferson, which the commanders named along with the other two rivers.

On the return trip from the Pacific, the Clark contingent arrived at Three Forks on July 13, 1806. That same day, Sergeant Ordway and nine men headed down the Missouri to join Sergeant Patrick Gass and his detachment of the Lewis party at the Great Falls; Clark and the 12 people in his group headed eastward overland to explore the Yellowstone River.

In the spate of fur-trade activity that occurred in the years immediately following the expedition’s return to St. Louis, the Three Forks area was heavily trapped. Three of the participants were erstwhile members of the Lewis & Clark Expedition: John Colter, George Drouillard, and John Potts. They experienced some hair-raising adventures with the Blackfeet, which resulted in the death of the latter two.

Probably in 1808, a few months after he had become the white discoverer of the present Yellowstone National Park while on another venture, Colter was wounded in a battle near Three Forks between a large party of Crows and Flatheads and hundreds of Blackfeet. The latter were repulsed. Colter, who was leading the Crows and Flatheads to trade at Manuel Lisa’s Fort Raymond, on the Yellowstone River at the mouth of the Bighorn, had no choice but to join them in the fight. Nevertheless, his participation apparently was one of the major reasons for subsequent Blackfeet hatred of American traders and trappers.

No sooner had Colter recovered from his wounds than he and John Potts, operating out of Fort Raymond, were trapping on a creek flowing into the Jefferson River a short distance from the Three Forks, when a band of Blackfeet surprised them and ordered them to bring their canoes to shore. Colter complied; Potts died when he refused, but not before he killed one of his adversaries.

The Indian chief decided to give his young warriors the sport of running Colter down on the prickly-pear-cactus-studded plain. He was stripped of his clothes and moccasins and given a hundred-yard head start. Outdistancing the braves who were in hot pursuit, bleeding from the nose and mouth from the exertion, Colter managed to reach the Madison fork, about five miles distant, killing one of his pursuers en route. Diving under a pile of driftwood and brush in the stream, Colter found a place where he could keep his head above water. Through an opening in the logs, he watched the Indians search for him and, on several occasions, walk over the driftwood. After dark, he swam downstream, crept to the bank, and started overland for Fort Raymond, about 200 miles eastward. Exhausted and almost starved, he made it in 11 days.

Lewis and Clark, the first documented white men to visit the locale, found it teeming with wildlife. For this reason, it was a meeting place and disputed hunting ground for various Indian tribes.

Back again at Three Forks that winter, Colter once more almost lost his life, this time on the Gallatin fork, when Blackfeet nearly surprised him in his camp one night. But by another herculean effort, he escaped to Lisa’s post.

Colter made his last visit to the Three Forks in the spring of 1810, guiding there from Fort Raymond a party of 32 French, American, and Indian trappers under Col. Pierre Menard. Included in this group or in reinforcements, who soon arrived and brought some 80 men, was George Drouillard. On April 3, the trappers began erecting a palisaded fort.

On April 12, a group of 18 men, Colter among them, who were trapping along the Jefferson, scattered from their base camp when Blackfeet discovered it. The Indians killed two men and three others were never found. Colter and the other trappers escaped back to the stockade at Three Forks. After this episode, Colter apparently decided he had exhausted his luck with the natives. On April 22, he and two others set out eastward, but once again Colter foiled an Indian attack. He went back to St. Louis and never returned to the mountains.

In May, only a short time after Colter’s departure from Three Forks, Drouillard died along with two Shawnee Indian companions in an ambush while trapping along the Jefferson with a group of 21 hunters. His decapitated and mutilated body was buried at some unknown spot in the Three Forks area.

The continual Blackfeet threat, as well as trouble with grizzlies, caused Menard to abandon the post later that same year. He led part of his group back to the Yellowstone River. His second-in-command, Col. Andrew Henry, led the larger part of the trappers westward across the mountains to a point outside the range of the Blackfeet. He erected a small post on present Henry’s Fork of the Snake River in Idaho, the first American fur-trading establishment on the western side of the Continental Divide.

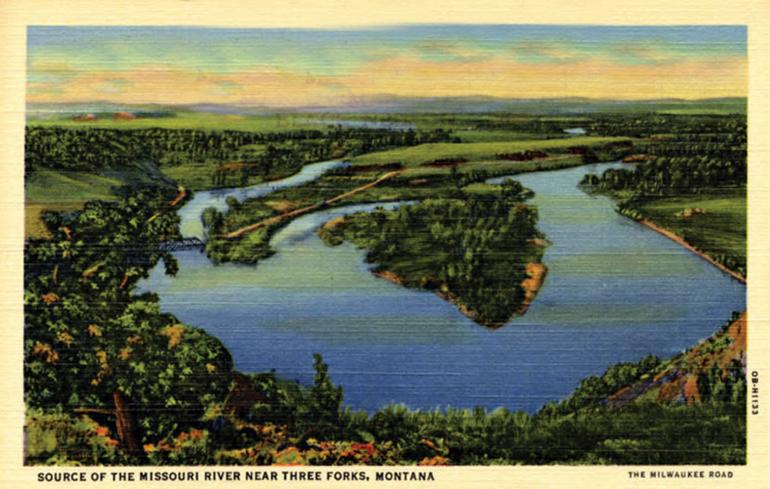

Few modern intrusions mar the Three Forks area, an oasis-like delta. The drainage pattern is essentially as it was in the days of Lewis and Clark. And, unlike so many other parts of the route, dams do not obstruct the streams in the vicinity. The town of Three Forks, situated about four miles southwest of the river forks amidst the trees of the delta area, is unobtrusive and all but lost in the vastness of the scene. Other modern features include a bridge over the Gallatin near its mouth on the access road (Hwy. 286) running to the forks; the Milwaukee Road, whose track follows the west bank of the Missouri to a point a short distance southwest of the Gallatin’s juncture with the Missouri; and the Northern Pacific Railroad, whose line follows the other bank of the Missouri and proceeds along the Gallatin a ways before bending eastward.

All the property in the Three Forks area is in private ownership, except for nine acres of the ten-acre Missouri Headwaters State Monument; a cement company, whose plant is at Trident, a hamlet a few miles northeast of the Three Forks, owns an acre of the park. An overlook provides a panoramic view of the area, and interpretive trails give access to key points. A prominent physical landmark visible from the overlook, across the Gallatin River and about half a mile from its junction with the Missouri, is the limestone bluff that Lewis climbed when his boat party first arrived at the Three Forks.

This article is adapted from the National Park Service’s online book about Lewis & Clark, available here.