Angle for the River

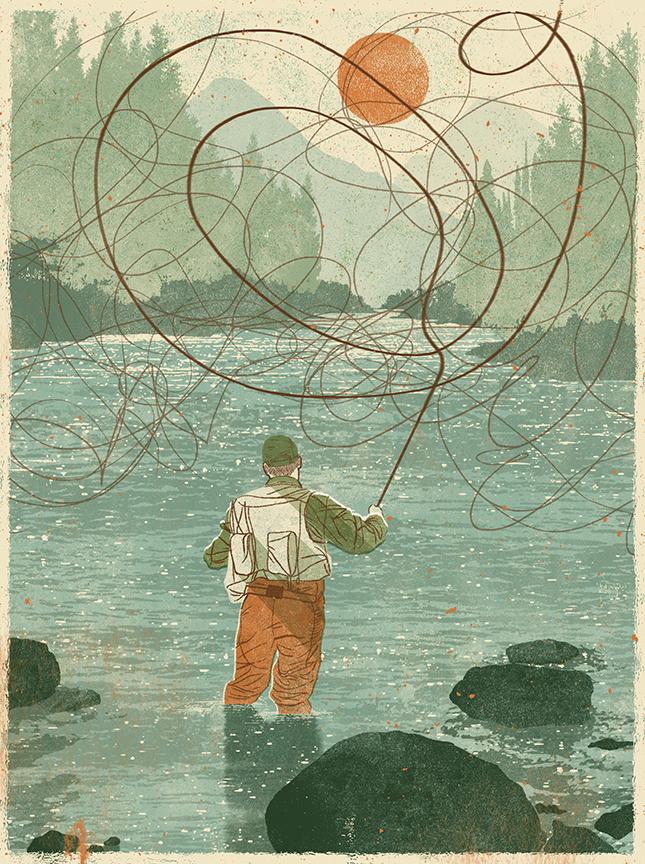

"Angle for the pond itself," Henry Thoreau advises, "the hook of hooks!" Walden Pond had no silver rainbows in his day, but our beloved clear Gallatin does. And so we fish for fish, though we have the opportunity of seeing the river all the while. Because it is a green riparian corridor that canopies the summer herds in the valley and runs from a lush canyon, this favorite river is not just a fishing pleasure ground but a splendid nature retreat as well. Without a rod, the Gallatin’s bright water ought to be walked with binoculars and receptive senses every year of our short lives, especially in June and July when bird song and the flowering landscape are in their absolute heyday. It is a gem of great perfection and beauty, in Bozeman’s back yard.

On a fresh morning, the best time also to fish this river though the canyon winds make your hands tremble, walk down the east side in the valley. Above the voices of falling water, up from the fragrance of the wild roses that nearly stops your way by the rail fence, listen for the birds that will be with you all the day long. The swallows you notice first. Tree swallows, in trim blue and white, tirelessly course the river after mayflies. So too the barn swallow with the forked tail, who arrives from Argentina to nest under Williams Bridge, and the plain brown bank swallows and rough-winged swallows who quickly join any of the several hatches that revive daily. The house wrens seem to be everywhere dead cottonwood is found, their bubbling rolls and trills and sizzles continuing most days through high noon. As you walk, watch for blue larkspur after late May, for lupine, and for the spikes of early purple phacelia among the sage and yellow mules-ears. As Thoreau also reminds us, "heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads."

Out on the Gallatin’s willow-thick islands, listen for the wheezy call of the willow flycatcher, one guaranteed on each isle, and for the song sparrow, our faithful companion from the winter months now singing even through the noonday sun. A brown spotted sandpiper, always in a state of panic, may startle you with a high whistle as he teeters on the wet rocks, and don’t miss a bobbing mink as he slides along the river’s edge or the fat grumpy marmot watching you a little higher up. The yellow warbler and the warbling vireo sing every other minute from the nearby woods, one low bush seemingly answering the other, and the kingbird, full of spleen, has enough energy in the warm sun to thoroughly complain at your intrusion. A kingfisher can be heard rattling upstream. Out in the fields, where the snipe with the foolish long bill sits on a fencepost, the distant grasses wave and shimmer in the heat. But you will have your lunch by the moving water in the shade where the rich cool air is luxurious.

As the evening comes on, walk to the pool with the cottonwood and thick aspen stands behind you, where the mayflies rise as the wind falls. The Spanish Peaks now are light blue and pink, like an oriental painting. Nighthawks, batlike, twist and turn in the light to the south. Listen here for one of summer’s finest hours, the veeries, the tawny thrushes that sing at dawn and dusk in only the wettest places. The song is liquid and ethereal, spilling and winding downward, insistent as the light fades, "veer, veer, ver, ver," like voices of spirits who walked the Indian trail along the benchlines to the west. In the quiet mood of evening as you amble back to the car, consider the day, how time was cheated, with no misgivings, no feelings of wasted sun. Without a portion of these days, no one of us should have to go.