Meet Mister Brown

Hope springs eternal in the deep pools of a mountain stream.

It is August, that thick season of harvest and summer fading in a series of hot days, a time of sunburn and sweat. Hay bales are bucked onto slow-moving pickup trucks grinding along in low range, and you think about going to the mountain to get away from the heat, or at least to cut a load of firewood. August means gather and get ready. Fall is coming and you find yourself squinting up at the mountain through the sweat and remembering places where you saw bull elk and buck mule deer last fall. Tall backcountry, away from roads and people and in wildlife heaven. Better shoot the aught-six a bit.

One summer afternoon, work slows when a lightning storm swells over the sagebrush and big globs of water spatter across the bug-stained windshield of the old Ford. The storm drops enough water to wet the downed and unbaled hay and it stops work entirely. You grab a rod and head for the hills. There’s a stream that comes down out of a limestone canyon, pooling and dropping, dancing between man-sized white boulders. Some of the holes are deep, so deep you can’t see the bottom. Looking down into that indigo depth, something like fear edges into your heart. The stream is not large, but its depth is formidable. There could be anything down there.

You try lures at first, drifting spoons out into the pool, letting them drop down out of sight, a little silver glitter in a sea of deep, dark blue. Winking diamond-like, then star-like. Then out. When the line stops, you start to bring in the lure, and it rises from the depth, swings into the current, and comes on. You do this for a while, and you catch a few decent rainbows, enough to feed the hay crew a good supper. You kill them quickly and clean them in the cold water of the stream, pushing a thumb up the bloodline against the spine, thinking of fresh fish for dinner and of cold streams. You thread them through the gill plate onto a willow branch and place them in the cold water of a side channel. There’s the smell of hay on your jeans and shirt, but your hands smell of fish. Not a bad thing.

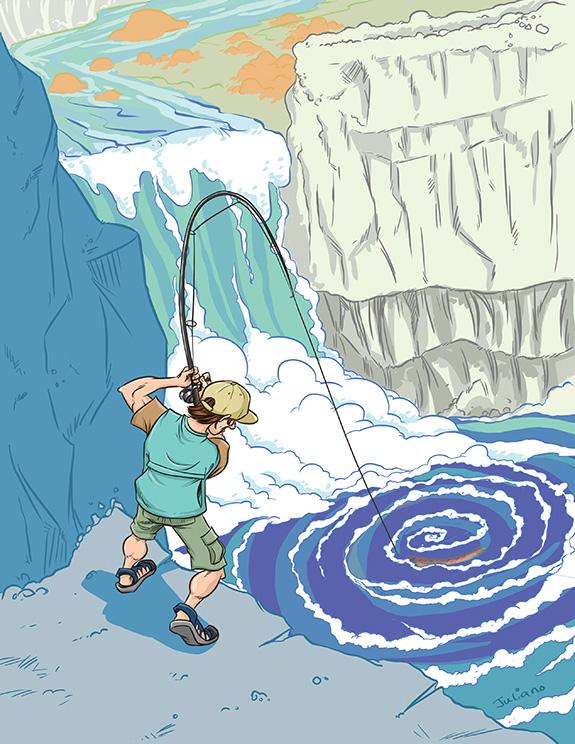

Upstream a mile or two, there’s a place where a huge pool is formed at the tail of a small waterfall perhaps three feet in height. During the spring, this place boils and rolls with big water and the waterfall is gone, but now, late in the year, it is there, lipping over the white limestone, dropping into the pool. This is the place where you lost a good Rapala last summer during the same kind of hay-meadow respite. That darned lure had cost five dollars. It felt like a snag at first, but in the big clean pool, there couldn’t be much to snag on. Then the line had started to move and your rod bent double and you cranked, hoping the eight-pound line would hold up, that something as stupid as a poorly tied knot wouldn’t be the end of it. The fish had stayed deep and didn’t seem to tire much. It swam and pulled, but didn’t make any big runs. Instead it was more like an anvil swimming around down there out of sight and when you finally had enough, when your arms couldn’t take it any more, you made one hard strong pull. It had been sufficient and the fish surfaced long enough to be seen and to see you. There was a tremendous splash, and then it was gone, and so was that five-dollar lure. Broken swivel. A two-cent part causes the loss of a five-dollar one. Kind of like ranching. You had seen enough though, a butter-yellow slab of a side, a hooked jaw, a mouth big enough to eat ducklings. Five pounds? Ten? No telling. Besides, you aren’t good at that anyway.

That kind of thing is hard to get out of a fella’s brain, hard to erase. You have flashed to it all year long, memory and dream. Now it is another year, and you’ve got another five-dollar lure in the box you carry in your shirt pocket.

The hike up there is not long, but you step carefully. The canyon belongs to things that bite and sting—rattlers and poison ivy and stinging nettle. It’s almost as if they are guarding the fortress of Mister Brown. You take all the right precautions and find yourself at the tail end of the deep pool where you rig up that new lure and weight it down and cast it out there into the black water where you can watch it sink for a long time until it winks out. Then you start a slow retrieve. Cast. Retrieve. Cast. Retrieve. Nothing.

Finally, you go to the backup, two thick nightcrawlers coiled in black soil in an old Skoal tin from your other shirt pocket. You thread the nightcrawlers onto a hook, feeling them squirm at its stab, and you tie the whole works down with a heavy weight and make a big cast into the deep pool. You watch the line as it feeds out, catches the current and starts to swing out. The line has all of your attention, and then it stops and you lift the rod into something solid and fearsomely heavy. It feels just like last summer felt. There’s muscle memory there, the weight of the fish transferred through the rod to your forearms.

This time, you have learned from your mistake and you wait a long time as you reel and give line. No need to hurry it. The fish fights deep and fights slow and finally, you feel as if you are gaining ground. In the absolute clarity of the water, you can see him now, swimming deep, a long black form in the depth of it, and you pull hard on the rod, trusting the line and not using a two-cent swivel this time. The fish follows the pull of the line, and you have him close now, close enough to net him. You reach out with the net and start to slip his long head into it.

For a minute there, you make contact, your eyes and his. That cold eye. That is enough. One connection and he gives one last big shake of that hooked jaw and everything comes loose. You dive forward with the net, almost going into the drink, but it is too late. A head-shake, a flick of that big tail. He’s gone. Back into the depths of the pool. Back into your dreams. Stored there until next year.

So long, big man.

Tom Reed is the author of many books including Blue Lines. He lives in Pony.