Wolke's World

A personal crusade for Wilderness.

As of late, one of the most important acts of environmental advocacy that conservationist and longtime Wilderness guide Howie Wolke partakes in is a small one: he hands a self-described “propaganda” packet to his clients—a list of Wolke-approved conservation organizations.

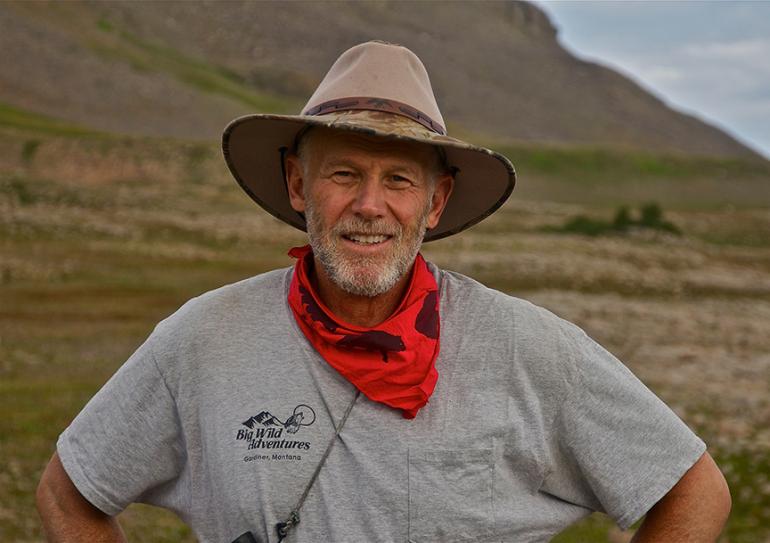

For 37 years, Wolke and wife Marilyn Olsen have run hundreds of guided trips out of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem through their outfit Big Wild Adventures. In that time, Wolke himself has guided over 500 week-long trips in more than seven states and on every type of public land. Wolke has spent an even greater amount of time as a well-known grassroots activist for a number of organizations, ranging from some of the best known in the conservation movement to small campaigns focused on protecting much of the land that the people of Bozeman consider to be their own back yard.

This small gesture at the beginning of each trip is the client’s introduction to developing a personal and working definition of wilderness as they take their first steps onto some of our country’s most sacred public lands, public land itself being an unfamiliar notion to many residing outside the American West. But for Wolke, the singular notion of defining wilderness has propelled him into his life’s work, both personally and professionally.

Wolke fell in love with the outdoors as child living outside of Nashville, Tennessee. Near his home was a state park, and it was here that he first encountered public land and developed a deep-rooted passion for all things outdoors. His childhood dream of becoming a forest ranger led him to eventually study wildlife ecology with a minor in conservation at the University of New Hampshire. He graduated from UNH in 1975 and lit out for Wyoming’s Rocky Mountains, where he traded in the dream of forestry for work in field studies for the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club. By this time, Wolke was an avid backpacker and outdoorsman, and he funded his conservationist lifestyle by picking up part-time work in construction and on ranches, while logging miles in some of the country’s most spectacular wilderness areas.

“I was literally in the bottom of a ditch when I decided to start a guiding business,” Wolke says of the start of Big Wild Adventures. He guided his first trip in the summer of 1979 in the Grand Tetons, and for a long time he worked as a bouncer at Jackson Hole’s famous Cowboy Bar, among other odd jobs, to augment his guiding income. In 1985, he met a registered nurse named Marilyn Olsen, who would become his wife. And in 2003, after years of running their business from outside of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, they set permanent roots outside of Tom Miner Basin, the place they currently call home.

For many years, guiding was the means to an end for Wolke. It enabled him to make a living working in the backcountry, while back at home his time was spent on the front lines of the conservation movement. Wolke has campaigned for wilderness protection in two ways: advocating for the protection of public lands that could qualify as Wilderness under the Wilderness Act of 1964, and ensuring that the protections of the Wilderness Act are actually enforced on current designated Wilderness.

Both avenues of Wilderness advocacy have their own sets of difficulties. Wilderness as defined by the Wilderness Act has to meet four basic criteria: the land is affected primarily by natural forces, it has the opportunity for solitude and primitive recreation, it contains at least 5,000 acres, and it contains ecological, geological, or other features of value. The Wilderness Act itself poetically sums up the meeting of these four requirements:

A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.

It’s a beautiful sentiment, but one that comes with conflict for those lands that hold potential for protection. The biggest threat to public lands that do meet the criteria for protection—often referred to as de facto wilderness—has been the building of roads and other structures, as well as the use of both motorized and mechanical vehicles, all practices that are forbidden once an area is designated as protected Wilderness.

“I’ve seen a lot of roadless areas that I was in love with impacted by forest-service roads, timber-sale projects, and off-road-vehicle use which destroy their potential for being protected under the Wilderness Act, and once the damage is done, it’s done,” Wolke says. These include such areas as Wyoming’s Grayback Ridge in the Bridger-Teton National Forest and Arizona’s Cabeza Prieta Wilderness, now overrun with both drug traffickers and Border Patrol attempting to keep up with the former.

If a tract of de facto wilderness doesn’t befall these destructive uses—something that Wolke describes as the “taming of wilderness”—and does indeed qualify for protection, Congress is the only avenue through which it can receive designation. And once designated, the tenets of the Wilderness Act are to be enforced on those lands into perpetuity.

But that’s easier said than done. Blatant misuse, lack of resources, and a history of lax accountability has plagued many protected Wilderness Areas, something Wolke has fought tooth and nail since the 1970s. As president and board member of the group Wilderness Watch, Wolke and his team seek to hold the United States government accountable for the stewardship of the 110 million acres currently designated as Wilderness through citizen oversight, public education, and legal action when necessary. One of the areas that Wolke is currently fighting to protect is one that many Bozeman residents set foot on every day: the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, a 500,000-acre swath of true wilderness that stretches from Yellowstone’s northern borders through the northern Gallatin range to our beloved Hyalite Canyon.

Designated as a Wilderness Study Area since 1977, 150,000 acres of the Custer-Gallatin National Forest is currently managed as a protected wilderness, but Wolke and a number of devoted Montanans are proposing that an additional 300,000 acres are protected through a project they’ve created called Montanans for Gallatin Wilderness.

“It’s a world-class wildland resource, it’s some of the best wildlife-protective habitat, and one of the best remaining unprotected habitats in the lower 48,” Wolke says of this particular stretch of the Custer Gallatin, which also happens to make up his actual back yard, a wildlife-rich landscape that’s frequented by grizzlies, black bear, lynx, wolves, elk, moose, and much more.

“There is something fundamentally different when you’re deep in a wild area when you can go for miles in any direction and not hit society, but it’s also fundamental for the wildness within us humans,” Wolke explains. “We still have this opportunity in the Northern Rockies and in the Gallatin Range.”

Wolke is known in the conservation community as a bit of a rogue. At a recent public meeting discussing the WSA in the Gallatin Range, Wolke stirred the pot by challenging more mainstream conservation groups. At one point, the panel's moderator had to cut him off, to which he responded, "I will not be silenced!" For an activist who cut his teeth working with both the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club, he doesn’t have many nice things to say about them or the other big political cogs of conservation. “A major reason we began Montanans for Gallatin Wilderness is that we perceived that the bigger conservation groups weren’t doing anything about the Gallatin Range at that point in time. Throughout my history as an outfitter and a proponent for Wilderness, I’ve seen how the face of the conservation movement has changed over the years. Some of the bigger, well-funded organizations have in my mind strayed from their original missions,” Wolke contends.

These days, Wolke’s propaganda list consists of organizations rooted in their localities, standing on the front lines of conservation in ways that Wolke believes the larger organizations often can’t. The list includes Friends of the Bitterroot, the Western Lands Project, the Alliance for the Wild Rockies, and Wolke’s own organization, Big Wild Advocates.

Handing his clients that packet is really the beginning of a journey into a state of wildness that they never knew existed. For those of us who make Bozeman our home, wildness is often at the core of what keeps us here, and access to public land is often just around the corner. But for Wolke’s clientele, that access in itself is an altogether foreign concept.

“One of the things a lot of our clients tell us at the end of a trip is that our trips are the highlight of their life, they’re life-changing experiences, both from the standpoint of people not realizing what’s out there until they experience it from the ground and, while it’s not our goal, we’ve had people come on trips and then literally change their lives—their locations, their professions...” Wolke pauses for thought. It’s a pregnant pause and you can almost hear a different wheel of conservation advocacy beginning to turn.

“Over the years, my personal emphasis has changed,” he explains. “When I got out of college in 1975 and started working as a conservationist, I viewed myself as a conservationist first, then started my guide business to support my conservation work, otherwise I was doing the hard labor. And this has done a flip-flop. I spend far more time out guiding and running the business than I do working on conservation issues these days.”

Wolke and his wife have talked a lot about this notion, that perhaps the fundamental nature of their own personal grassroots work is undergoing a major shift from the political to the personal; that these life-changing experiences might be the way to lasting change after all.

But the sense of urgency around protecting these public lands and the treasures they hold is still the main current of Wolke’s lifeblood. “Our clients aren’t coming to be walked around through pretty scenery, they’re coming for wildness. And wilderness without all of its wildlife is a tamed wildness. If we lose these aspects of wildness—the howling wolves, the grizzly bears—then we lose the essence of what differentiates the Northern Rockies from the rest of our country,” Howie contends.

Underneath these conservation efforts lie the contentious underpinnings of the politics of the American West. The use of ORVs, snowmobiles, and mountain bikes in Wilderness Areas; the reintroduction of apex predators into the ecosystem; the current push-and-pull of the state of federally-governed public lands in America—all complicated issues rooted in our own localities that often divide us. And the politically dichotomous views are consistently becoming grayer when it comes to these conflicts—the issue of public lands has no longer divided itself across party lines like so many other issues at hand; it’s become one that’s intensely personal.

For Howie Wolke to believe that he might be doing the biggest amount of good at the client level isn’t so farfetched. “We still have big Wilderness and the chance to protect big Wilderness. Whenever we have a chance to protect big wilderness like the Gallatin Range, we should not take that lightly.”

For once the roads are built, they’re there forever.