Lighten the Load with Llamas

"Let's go llamas!" So sings German-born Susi Sinay, with emphasis on the first and last words, as she sets off down the Daley Creek Trail in the backcountry of Yellowstone National Park. Her refrain is repeated each time we return to the trail from a rest period, as if the llamas require instructions; but they seem to know what to do intuitively. Born to pack. Born to follow.

Susi’s husband Ken, a wildlife biologist, brings up the rear. In file between the two, in no particular rank, are we five guests: Rich, a college student from Minnesota; Brian and Sharon, a couple from Baltimore; and myself and wife Andra. Seven humans. Seven llamas.

The mountains in the distance, toward which we head, still have broken ribbons of snow along the ridges, and given the nature of our transport, it seems we might just as easily be trekking in the Andes. The llamas are curious and calm. One thing they aren’t too fond of, I find out early on, is getting their feet wet, preferring to jump rather than ford the many streamlets running down out of the snowfields. You’d better step aside lest the gear-filled panniers knock you flat. Andra caught one in the back and went down fast. Face in the grass. No harm done.

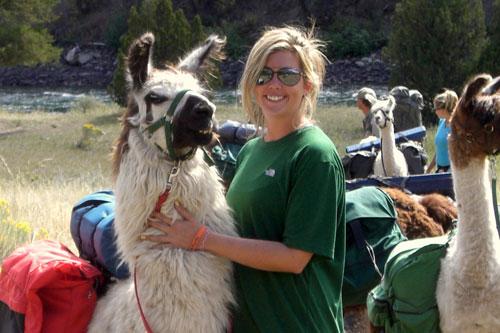

My first thought about Yellowstone Llamas was this: “No 50-pound pack on my back. Cool!” Each llama can carry that much weight in two equally sized panniers or saddlebags. By the end of the season, when they’re in better shape and stronger, 60 pounds. Suzy has been running llamas as pack animals for 14 years and knows them intimately: Don Giovanni. Yukon. Dot.com. Amadeus. Cooper.

We lead our llamas on through fields of owl clover, pussy toes, lupines, vetch, phlox and blue flax, the grasses still spring green. Camp is made 5 miles in from the parking lot where we left our vehicles. The llamas are unloaded and tethered in an expansive meadow with views west toward the Gallatin River valley from whence we’ve risen. To the east, above us, looms the Gallatin Range. Dinner this night: bison chili, rolls, pudding and fruit, and white wine.

The next day Susi stays in camp while Ken leads us up the mountain to the Sky Rim Trail, through forests of whitebark pine decimated by the pine bark beetle as well as by blister rust. On the ridge, the wind roars up from the Tom Miner Basin below, cold and strong. In the lee, it is serene and hot, so as we work our way along the Sky Rim Trail, alternately exposed and protected depending on which side of the ridge the trail follows, we continually add layers of clothing, and take them off. Ken shows us elkhorn lichens shedding spores, shooting stars, and glacier lilies, whose roots the Northern pocket gophers break off and cache; they’ll feast on the stockpile over winter—if bears don’t find them first.

Rich decides we are too pokey and strikes off ahead for Big Horn Peak several miles south. Brian and Sharon elect to nap in a wildflower meadow out of the wind. Swallows flit above the treetops; a lone eagle circles in the updrafts.

Ken leads Andra and me on up the trail another half-mile or so, through sculpted snowpacks that might never entirely melt before it snows again. Bent on finding us wildlife, Ken carries binoculars and a scope. Scanning the next peak ahead of us, he finds several bighorn sheep on a rock wall, and we take turns watching them feed and maneuver among the rocks and slides and stumps of petrified trees.

In late afternoon we descend to base camp. Susi has busied herself all day moving and watering the llamas, prepping dinner, and reading a good book. At dusk we hear wolves howl. Temps drop precipitously and we eat by the campfire. As darkness falls Ken gives an animated recreation of Colter’s Run, in which the former member of the Lewis & Clark expedition outran, naked, a band of spear-chucking Indians, dove into the Jefferson River, and saved himself by hiding inside a beaver den.

Leading my llama out the next day, I realized this trek is much more than just letting an animal carry my load; it’s about a guided experience into the backcountry, far from any sign of human activity or presence, and perhaps best of all, learning about the flora and fauna from someone who has the education and a lifetime of experience to explain many mysteries of nature.

For more information about llama trekking, contact Yellowstone Llamas at 586-1155 or visit yellowstonellamas.com.