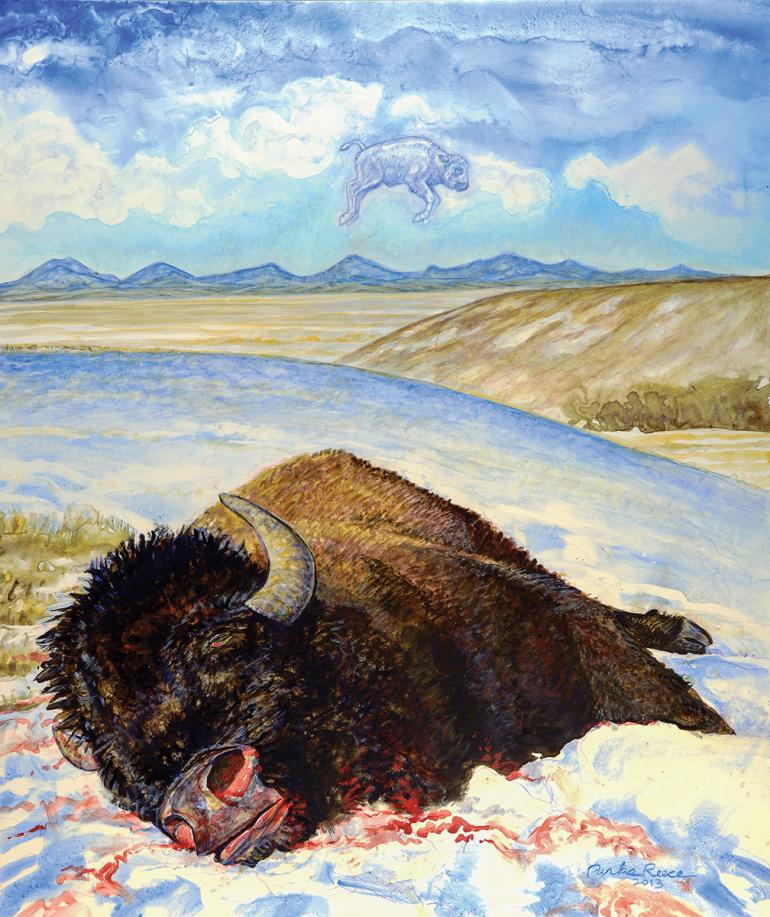

In the Crosshairs

A home where bison can’t roam.

It’s no bull: managing Yellowstone bison is a complicated task. As wild animals, they’re programmed to migrate, and their paths frequently take them outside of the Park’s 2.2 million acres. The result is an annual bison hunt just beyond the northern border of the Park. It’s controversial, and profuse with politics, emotions, and questionable management decisions. This past winter, I took a closer look at the hunt.

Slaughter Grounds

Usually following a significant snow event, bison from the Park’s northern herd follow an ancient migratory urge pulling them toward lower-elevation habitat and accessible winter forage. The bison pass through the Roosevelt Arch, then head north along the Old Yellowstone Trail, their migration corridor framed by the Gallatin Range and the Yellowstone River. Eventually, they cross an invisible line separating the Park from Beattie Gulch in the Custer-Gallatin National Forest. At that point, they’ve left the protection of the Park. A line of tall posts capped with orange markers roughly marks the zone within which hunters wait, gathered en masse, to harvest the bison, assuring an almost 100% mortality rate for the unsuspecting animals.

Some describe the hunt as dangerous, inhumane, and unethical; the hunters, a firing squad. Although wardens from various agencies and tribes monitor the hunting and can close the road or stop the hunt if necessary, few rules seem to apply. In the antithesis of a fair-chase model hunt, hunters simply stand near their trucks, rifles ready, waiting for the bison to enter the kill zone. The hunters are mostly tribal members exercising treaty rights granted in the 1880s, but a limited number of public hunters round out the field.

With the bison hunt in full swing, on the last day of 2022, I headed to Beattie Gulch with my husband and our friend, Dr. Nathan Varley, a longtime Gardiner resident. I dreaded what we might see, in an area we’ve always known as a reliable place to find tranquility in spring and summer.

Crossing under the arch, we slowly bumped and slid through several inches of fresh snow along Old Yellowstone Trail. Uphill on the left, a few pronghorn dotted the landscape; then, rounding a corner, we slowed to admire a couple dozen bighorn sheep loosely scattered on the right. A full-curl ram raised his head, acknowledging our passing, then nonchalantly resumed grazing.

Scanning the landscape, we looked for death, or signs thereof. No bison, dead or alive, were in sight, nor were there any hunters. Then, up ahead on the right, we spotted dozens of ravens careening above, some landing upon huge tan boulders on the hillside, others perching atop small pink remnants of gut piles.

Although wardens from various agencies and tribes monitor the hunting and can close the road or stop the hunt if necessary, few rules seem to apply. In the antithesis of a fair-chase model hunt, hunters simply stand near their trucks, rifles ready, waiting for the bison to enter the kill zone.

We hiked through an icy snowdrift, then uphill toward the boulders, which, as Nathan pointed out, were actually dried bison stomachs, most easily two feet in diameter. Bits of bison hide, tracheas, and a few internal organs were all that remained of what once was a small herd of Yellowstone bison.

Back on the road to Gardiner, we passed more bighorn sheep posing for photographers, and private residences posted with “No Hunting” signs. Then we spotted the only live bison we encountered that day: a small herd grazing in a no-hunting zone on the east bank of the river, below Hwy. 89.

Muddied Waters

The impetus for the bison hunt boils down a tiny bacterium, Brucella abortus. The bacterium causes brucellosis, a disease which has historically been transmitted between and among bison, elk, and cattle via contact with infected birth tissue. While not inherently lethal, the disease may cause its female victims to abort their calves, leading to reduced calf recruitment. Containing the spread of brucellosis is tricky, however, because of the different jurisdiction these three host species are under. Elk are the sole responsibility of Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, regardless of where they are in Montana. Private land or public—it doesn’t matter; elk are wildlife. And brucellosis rates are relatively low in elk, despite overlapping in rangeland with brucellosis-infected bison. Only about 2-3% of elk in the Park are estimated to carry the disease.

Bison, on the other hand, are considered wildlife when in the Park, but livestock immediately upon exiting. This differentiation dates back to a law passed in the ’90s, that handed authority of migrating bison over to the Montana Department of Livestock (DOL), taking it out of the hands of the Park Service. The law was a direct result of political pressure from ranchers concerned about the spread of brucellosis from bison to cattle. And while there’s a vaccine that protects cattle from the disease, it’s not 100% effective. Nearly 15% of infected, vaccinated cattle still abort their calves. Ranchers consider this number to be too high, and they place increasing pressure on the state to stem the disease at its source: bison.

According to Dr. Martin Zaluski, state veterinarian with the DOL, the state has looked at multiple solutions to this problem, including vaccinating bison against the disease. “Suppression of brucellosis in bison to the rate found in wild elk would provide a reasonable argument to modify bison tolerance,” Dr. Zaluski sys. “When Yellowstone Park explored the possibility of in-Park brucellosis vaccination of bison to reduce infection rates, DOL supported that proposal.” But, according to the Park Service, there is no easily distributed, highly effective bison vaccine: current vaccines would only create a 10-15% reduction in infection, and immune protection would be short-lived. (For an alternate viewpoint, see "Vax Unpopuli" at the bottom of this article).

And although possible, bison have not actually been known to transmit brucellosis to cattle. Ever. Rather, elk are the source of all cattle infected with brucellosis by wildlife in the Greater Yellowstone area. Over the past several decades, elk have been known to transmit brucellosis to cattle numerous times. But that doesn’t mean bison are off the hook. Bison act as a reservoir for the disease, and can transmit it to elk, which frequently graze in areas where bison are calving (meaning elk are frequently exposed to the disease in the Park). The elk, in turn, can infect domestic cattle. As such, the state turned to hunting as a means of limiting bison contact with domestic cattle, and, to many, it’s just a political ploy when the true culprit is elk.

Eventually, the bison cross an invisible line separating the Park from Beattie Gulch in the Custer-Gallatin National Forest. At that point, they’ve left the protection of the Park.

Another solution, developed as an alternative to hunting, is the Bison Conservation Transfer Program, which allows for bison to be relocated, rather than slaughtered. The Park Service captures a number of bison each year and transfers them to pens such as the Stephens Creek facility in the Gardiner Basin. The bison are quarantined until deemed brucellosis-free, and then relocated. To date, the Fort Peck Indian Reservation has received 294 bison from the program, 170 of which have been distributed to 23 other tribes across North America. And while part of a larger solution, the program itself isn’t large enough to solve the entire problem, and it requires a tremendous amount of resources to relocate the animals.

Nonprofit Work

In late December, I incidentally met Gunnar Nemeth, a Buffalo Field Campaign (BFC) advocate, and Patrick Kincaid, a treaty law expert, at the Tumbleweed Bookstore and Café in Gardiner. Our meeting came just weeks before an incidental shooting, in which a bullet fragment stuck a Nez Perce tribal member while he was field-dressing a bison. Described as a “freak accident,” no charges were filed against the non-native hunter, whose bullet fragment ricocheted while shooting at a bison, striking the victim from 400 yards away. It added fuel to the already heated protest from locals, calling the hunt a public-safety hazard threatening both hunters and residents in the area. BFC called it “unacceptable” and “clearly foreseeable.”

Despite the best efforts of nonprofit groups, the bison slaughter appears to be here to stay.

Nemeth and Kincaid had spent the week before monitoring the bison hunt in Beattie Gulch. They reported that 100 bison had been killed so far. BFC, a nonprofit committed to protecting Park bison, criticizes both the hunt and the management that allows it to occur. Their mission, in part, is to “stop the harassment and slaughter of Yellowstone’s wild buffalo herd.” BFC claims that over 10,000 bison have been harvested from the Park herd since 1985. And BFC isn’t the only organization fighting the hunt. In 2019, a group called Neighbors Against Bison Slaughter filed a federal lawsuit seeking to permanently block the hunt, citing safety risks. Many other Gardiner residents, including Dr. Varley, have long contested the hunt, as well. “I’m not sold on weak justifications for preventing year-round bison herds on adjacent public lands.” he says. “As a longtime resident and advocate for Gardiner, I would like to see more wild, free-ranging bison outside of the Park. Something has to give.”

Looking Ahead

Despite the best efforts of nonprofit groups, the bison slaughter appears to be here to stay. The Park Service is currently preparing an Environmental Impact Statement as part of an effort to update their 23-year-old bison-management plan. In the statement, they list three possible scenarios: 1) no change to current management; 2) increased tribal hunting opportunities; 3) increased tribal and non-native hunting opportunities. Notably absent is an option to cease the hunt altogether. Park Superintendent Cameron Sholly hopes to finalize the plan this year. In the meantime, Yellowstone’s wild bison will remain in the crosshairs.

Vax Unpopuli

While politicians and ranchers are busy bickering, Robert Lindstrom, former Research Coordinator for the Park, is advocating another solution: an mRNA-based brucellosis vaccine for bison. Lindstrom says that this kind of vaccine, similar to mRNA Covid-19 vaccines, would be far more effective than the “Cold War era” shots currently in use. And, based on preliminary testing, the new vaccine appears to have potential. Researchers at Montana State University found that the vaccine elicited a strong cellular immune response in bison, and, last year, Lindstrom helped a research team apply for a Park permit to test the vaccine on wild Yellowstone bison. But the Park Service denied the request. Lindstrom believes the decision boils down to politics, rather than the biology itself, as most of the research-and-development work has already been done. Decades of it, in fact. Lindstrom was part of a team that isolated a key PCR enzyme from hot springs in the Park back in the ’70s, revolutionizing the field of biochemistry and forming the foundation for developing mRNA vaccines (including those for Covid-19). Not only that, but the infrastructure—bison capture and quarantine facilities—in which to conduct the testing is already in place. Yet the Park Service “does not support testing a novel brucellosis vaccine on wild Yellowstone bison, including those… held in quarantine,” according to the rejection note. The Park’s reasons for this lack of support are enumerated in a Bison Remote Vaccination Environmental Impact Statement (EIS); but that EIS was completed in 2014, and Lindstrom believes that the new vaccine is promising enough to warrant reconsideration. And why not? There’s little to lose and much to gain. —the editors