A Tale of Two Treasures

In Bozeman, as with much of the West, tension builds between competing ideals—and striking a balance is no mean feat.

Like a steam locomotive screeching to a halt, my illusions of the American West came to a standstill several years ago. The West, for centuries mythicized by broad horizons and unobstructed valleys, had lured me in with its wind-tousled sagebrush and sun-cured grasses. I had no dreams of grandeur, no fictional hopes of becoming a ranch baron, but rather wanted to escape the snares of technology and the chaos of large cities I’d been bouncing between for work and school. I needed time and space for introspection, and what better place than a Montana cattle ranch?

I took up a job as a ranch-hand in the Flint Creek Valley, where the family put me up in an old house bordering the aptly named Cow Creek on one side, and a quarter-section of irrigated pasture on the other. Yearling steers bucked and played in my yard, and I could sit on my porch and watch elk feed across the lush foothills of the Pintler Mountains. Shooting gophers and building four-wheeler jumps with the John Deere? Yup, I could do that, too. I appeared to have found the unobstructed freedom I was searching for.

But as I chased and cursed at cattle across thousands of acres of rangeland, my honeymoon period with ranching began to wane. What had appeared, upon a cursory glance, to be boundless fields and free-flowing creeks, was a highly managed system for turning land, water, diesel, and sweat into pounds of beef. The stream behind my house was carefully regulated by a dam just a few miles upstream, and those pastures were tightly wrapped with barbed wire and electric fences. As my boss and I rattled around the ranch in his truck, he would point to collapsed cabins, proudly reminiscing about how his great-grandfather had settled the land and tamed Cow Creek with an earthen dam. While trying to reconcile my image of the Montana range with the reality of it, I had stumbled into the quintessential paradox of the American West: freedom vs. want.

What I found was both exciting and disheartening. I discovered that Bozeman represents a modern rendition of the timeless western paradox.

Alas, this is no new phenomenon. To have the West as we imagine it—expansive plains, room for the body and mind to wander—requires that we maintain it in its natural state. But to live and thrive in the arid landscape calls for taming the rivers, manipulating water, and bending the land to our tractors and houses. We can’t have it both ways. Therein lies the paradox. There’s a fundamental difference between what we want the West to be, and what it actually is; what it has to be.

After my illusion of the West came tumbling down, I packed my worldly possessions—a few fishing rods, a hunting rifle, a well-seasoned cast-iron pan, and a bag of clothes—into my Subaru Outback and headed for the mountains. I needed early mornings at high-mountain lakes and long hikes on alpine ridges; things that fulfill my soul in a way cattle ranching had failed to. I’d heard about Bozeman and knew that it was mythicized for its access to the outdoors. I’d also enjoyed stories from the rancher I was working for, who, after two semesters of living in a makeshift stairwell bedroom and scuffing barroom floors with his cowboy boots, dropped out of Montana State and crawled back to the ranch. After putting my way over Homestake Pass, I arrived in Bozeman with high hopes and expectations.

What I found was both exciting and disheartening. I discovered that Bozeman represents a modern rendition of the timeless western paradox. Like me, thousands of others are moving to what was once a quint Montana ranching town, many seeking refuge from the rat-race of large cities—San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle. Once in town, however, we desire the infrastructure to reach further into the wilderness, giving us access to areas that would otherwise be too far, too difficult to explore. We build roads, boat ramps, and trails cutting deep into the heart of the mountains, the very places we came to enjoy because of their remoteness. Then we want houses outside of town, so we can have a better view of the mountains—the irony, of course, being that to build on a piece of land up Bridger or Hyalite Canyon eats away at both the amount of undisturbed land, and the very essence of the rugged Montana Rockies.

In a place that, without infrastructure, could never support its current population, we’ve managed to create a community centered on the outdoors and our shared love of it.

At first, I was perturbed by this. My frustration culminated on a trip into Thorofare Creek on the upper Yellowstone, an area which, despite being only 30 miles from a road in any direction, is considered the most remote region of the Lower 48. Even there, as far from people as possible, I was startled by run-ins with horse-pack strings and other hikers. This, I realized, was freedom vs. want boiled down to its essence. A single trail diving into the heart of Yellowstone. Just as making fertile land out of the West required dams, gaining access into the wilderness requires trails. Blown up in magnitude, we arrive at Bozeman. An outdoor paradise? Yes, but not without sacrificing a good chunk of southwest Montana’s wild character. Which isn’t, as I’ve come to discover, necessarily a bad thing.

Although I would rather have the freedom of the West over an intricate patchwork of isolated mountains separated by irrigation ditches and “No Trespassing” signs, I also enjoy the amenities a city like Bozeman has to offer. In a place that, without infrastructure, could never support its current population, we’ve managed to create a community centered on the outdoors and our shared love of it. Without the compassion and respect that people in Bozeman have for the landscape, it could easily have ended up like parts of Idaho, where there’s a four-wheeler track to the top of every mountain, and Keystone Light cans are as ubiquitous as wildflowers. Conversely, however, we could love it to death, slapping on so many trail and area-use restrictions that it becomes impossible to enjoy the very resources we came here for. With no way to transcend the paradox of freedom vs. want, we must work within its bounds to strike a fine balance between preserving the unruly nature of the West while manipulating it to fit our needs.

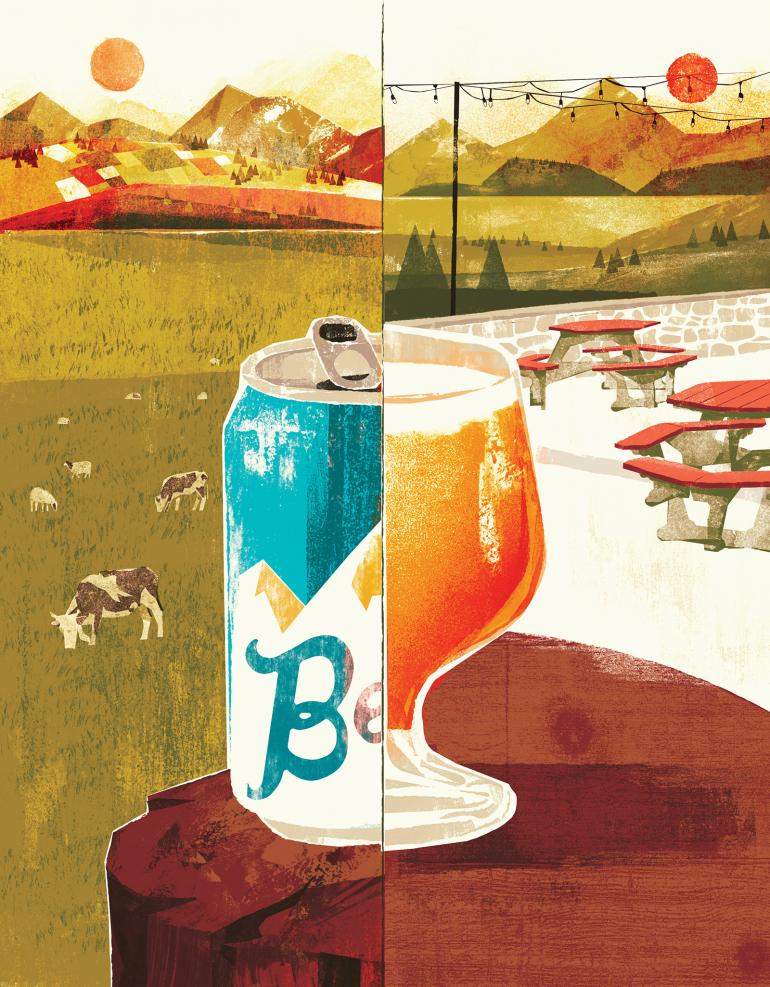

I, personally, have managed to find a good middle ground. Every couple of months I make my way back to the Flint Creek Valley, where the rancher, now a good friend, and I kick up dirt on his side-by-side, chasing terrified cattle across open range, stopping to cut down a few trees, shoot a coyote, or just admire his shiny-new center-pivot. It might not be the West I had imagined, but it’s close enough. And once I’ve bullshitted my way through as much conservative politics as I can handle, I head back to Bozeman and sip microbrews on the patio of some indistinct brewery overlooking the Bridger Mountains.