Rockin' and Rollin' with the Stones

On a long-ago road trip to a legendary hatch, two young anglers get salmonfly satisfaction.

“Dan Bailey’s,” the voice answered on the other end of the line.

Astonishing, I thought to myself, as I stood at a payphone in Sun Valley in late June of 1967. They aren’t just a catalog you drool over when it comes in the mail from the semi-mythical land of Montana—you can call the famous Dan Bailey’s Fly Shop and speak with real people! And they will talk to you and give you the scoop. How cool is this?!

That summer might have been the Summer of Love for some our age, but to us, it was the Summer of Trout.

I gripped the phone tighter. I was 19, a long way from home, and had just five quarters in my pocket to feed the black box on the wall before my time ran out.

“Uh, sir, can you tell me where the salmonfly hatch on the Madison is right now?” I held my breath, hoping this wasn’t a silly question, wondering whether they’d ask my name and try to book me a guide.

The cheerful voice at the other end of the line (in those days, there were actual telephone lines) said, “They’re coming off around Ennis right now, upstream near the Varney Bridge. You can fish dries or nymphs anywhere through there. The water is still off-color but not bad, and the flow is down enough to wade some—but be careful.”

“Sofa Pillows?” (I had read up.)

“You bet, but don’t forget the nymphs. They can be productive throughout the entire hatch. Not as much fun, but the best way to catch fish.”

“Thank you, sir!”

“You bet. Good luck.”

And that was that. Incredible. Straight information straight from Dan Bailey’s, the western Mecca of fly shops. To the point, friendly. What more could one ask? I was enjoying the West more and more each day of this summer sojourn.

Thanks to the efforts of Joe Brooks, our fly-fishing mentor back home in Virginia, my friend Bert and I had ventured west for jobs in Sun Valley after our first year of college. Bert patrolled the Olympic pool as a lifeguard, and I helped at the tennis courts. But we didn’t come west for jobs—they were just a bothersome necessity—we came to fish. That summer might have been the Summer of Love for some our age, but to us, it was the Summer of Trout.

We fished every night after work and all day on our Wednesdays off. We had Silver Creek almost wholly to ourselves—such was the world of western spring-creek fishing in the mid-1960s. But we also explored. Joe had told us about the salmonfly hatch on the big Montana rivers. The Madison was within a day’s reach. After our recon via Dan Bailey’s, we tied a few flies and plotted our route with our trusty Rand McNally.

The stoneflies and meadowlarks slapped their thighs and guffawed. The trout didn’t even know I was there.

Tuesday evening, after work, we rolled out in Bert’s old Chevy II and headed down the Wood River Valley through Hailey, Bellevue, and on to Idaho Falls. Along the way, we picked up Wolfman Jack on XERB—all 50,000 watts’ worth. No place in the West was too remote to escape the Wolfman, howling down from the starry skies with intros to the hits of that year: “Ode to Billie Joe,” “San Francisco,” “Windy,” “Satisfaction.” Making our way through Craters of the Moon, we took care not to stray from the almost-deserted two-lane while rocking it to Mick and the boys, trying to “get some.” We assumed, of course, that they were referring to brown trout.

Sometime after one in the morning, we ghosted into an empty Ruby Creek Campground on the Madison. On a slight downhill slope, we faced the river—a river that, in the darkness, sounded serious, as if it had things to do, places to go, and good luck to anyone who got in its way. Bert found sleep quicker than I, as he had done most of the driving.

Stars filled the moonless sky. More than I had ever seen at one time. There were also bright meteors—Pegasids—streaking the Big Sky toward Yellowstone Park, just frequent enough to keep me awake, awaiting the next. It was a grand show, the most incredible outdoor theater I had ever attended, like nothing I’d seen in Virginia. My first impression of Montana seared into my brain like a celestial fireball: I imagined cosmic cowboys astride the blazing cinders, waving their hats in the air with their free hands—flinging their ki-yi’s to the skies. I thought, One day I must move to Montana.

We were up the next morning well before the sun peeked over the Madison Range. We skipped breakfast—we had more important things on our minds. Our chief concerns were: what does this river look like in daylight, and where are these famous bugs? In the early chill, we scanned the skies, expecting stonefly flights of biblical proportions, blotting out the sun. We saw none. What gives? What do we do now? Are we in the right place?

Someone once described the streambed of the upper Madison as “greased bowling balls.” Someone was right.

We traipsed down to the riverbank, careful not to fall in lest the Madison sweep us to an untimely demise. Keeping a wary eye on the river, we searched along the shore for nymphal shucks. At last, Bert found one on a grass stem, then another on a rock, more in the willows. To our eyes, grown used to 5x and 6x tippets and size 18-20 mayflies on Silver Creek, these shucks told fantastical tales of insects of Jurassic proportions. But these were stonefly history—where were the stones of today?

We soon found out. Within an hour, the sun had warmed both us and the bugs. The salmonflies were flying. They thumped into our bodies and heads and crawled down our necks under our shirts. Dan Bailey’s had been spot-on—this was the place. Who needed to “wear some flowers in their hair” this special summer? We had stoneflies in ours. We were ready to fish.

Easier said than done. Abundant fringes of willow and birch lined this side of the river, perfect for shading the water and depositing bugs on its surface, but also perfect for complicating casting. And this was not Silver Creek wading. I think someone once described the streambed of this stretch of the Madison as “greased bowling balls.” Someone was right.

“You go first,” I offered.

“No, I insist, after you.”

We split up, as neither of us wanted to see the other one drowned, nor drown while trying, no doubt without success, to save the other’s life. Bert headed downstream, and I went up. No plans. “Tight lines!” we called.

I started near camp. In my leaky Seal Dri’s and homemade wading shoes, I edged into the river, murky with runoff—and almost ended up as flotsam headed for Ennis Lake. I stumbled back out, looking for a place with some relief from this sluicing monster. There was none. No boulders protruded above the surface to provide backwater—for the fish or me. How do these fish live here? And how do I fish for them?

A wading staff would’ve helped, but one of our many mantras at that age was, “We don’t need no stinkin’ wading staffs.” I tried again, edging into the river, somehow managing not to fall flat. I stood there, feeling the current pulse against my knees. Or perhaps I was just shaking in my shoes.

Within an hour, the sun had warmed both us and the bugs. The salmonflies were flying. They thumped into our bodies and heads and crawled down our necks under our shirts.

My first cast snagged a willow, the weighted nymph wrapping a branch and tying itself snug. With slime-covered rocks rolling under my feet, I lurched upstream, freed my fly, and cast again. Same result. I tried casting left-handed. No go, especially with the large, heavy nymph. I tried again right-handed, this time sideways under the brush, close to the surface—and snagged myself on my first back-cast. I shortened my leader, took a couple more steps out into the maw of the Madison, and tried again. Success of a sort. I could get out about 20 feet of line, but by the time I gathered my line to strip it or control the drift, my fly had raced by me in the current. At least I wasn’t bleeding or drowning, or both at the same time.

I looked around to see if anybody was watching. The stoneflies and meadowlarks slapped their thighs and guffawed. The trout didn’t even know I was there. I persisted with this upstream madness. Why, I don’t know. I was used to fly-fishing upstream, and I thought this was how it was done.

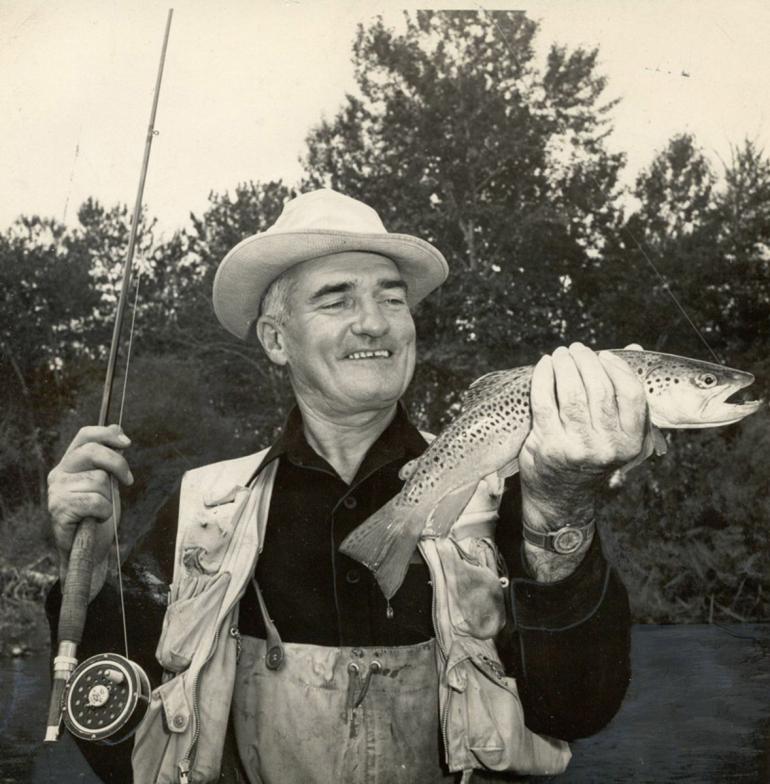

Like Mick and the boys, “I tried, and I tried, and I tried, and I tried”—all the morning, I tried. Around what should have been lunchtime, I hooked and landed a brown of about three pounds, the biggest trout I had ever caught; a Montana-sized trout. After releasing it, I felt a celebratory break was in order.

We broke down our rods, packed up, and headed out. We had glimpsed the fabled Montana, and we vowed to return.

That was when I encountered two much older (perhaps in their 30s) fly fishermen from Los Angeles. Imagine people coming all the way from L.A. to fish the salmonfly hatch? Crazy. They had seen me catch my fish and wanted to know about it and how I had done it. We discussed the challenges of wading and casting and the like. They noticed I looked worn out and asked if I was thirsty and where my water and lunch were. They weren’t anywhere. I had brought none of either.

I was nineteen years old and invincible, or so I thought. They knew I was not invincible, that I was just a kid, and they gave me water and a sandwich. At first, it irked me to meet other anglers on the river; Montana was a big state, and this was the middle of the week—Bert and I had figured we would have the joint all to ourselves. But, as we chatted, I decided these guys were okay, even if they were crowding me a bit. They walked downstream, looking for fish. I imagined them recalling their flown youth and perhaps envying my freedom at being able to, as Mama Cass wailed, “go where I wanna go, do what I wanna do.” No spousal supervision. No phone calls home at night from the far corner of the motel room ending with a muted, “I love you, too.”

I ate my gift sandwich on a rocky hillock overlooking a bend in the river. A cow waded into the Madison on the far side and the rushing river grabbed it. I braced myself for the worst, not wanting to witness a cow drown in this torrent. The cow tip-toed, floated, and tip-toed and floated and, to my amazement, made its way across. It climbed the riverbank, shook itself, and browsed the lush willows on the less-grazed western side. Like us, this cow figured things must be better “in the West.”

At least I wasn’t bleeding or drowning, or both at the same time.

Emboldened by this bovine with moxie, I eased back into the Madison: Unto the breach once more. The sandwich had rejuvenated me somewhat, but my morning struggles with the river had worn me down nonetheless. My casting suffered; my fishing suffered; I suffered. About the time I had drifted into a dazed, indifferent nothingness, I saw the fish.

At first, I did not recognize it as a fish. It was so large it undulated like an Okefenokee alligator. The trout backed downstream towards me, behind my fly—backing down, backing down, eyeing my nymph, evaluating it. Then grabbing it.

I jabbed my rod overhead, stripping line as fast as I could, trying to make contact, but there was none. As abruptly as the monster appeared, it disappeared into the murk. And that was that. I was done.

My first impression of Montana seared into my brain like a celestial fireball: I imagined cosmic cowboys astride the blazing cinders, waving their hats in the air with their free hands—flinging their ki-yi’s to the skies.

I got out and walked down along the river to the car. Bert was there, as exhausted as I was. He had not caught a fish, touched one, or even seen one. Long day. I recounted my various adventures and misadventures. We broke down our rods, packed up, and headed out. We had glimpsed the fabled Montana, and we vowed to return.

On the ride back to Sun Valley, we grabbed burgers in Idaho Falls. And perhaps a piece of apple, peach, or pumpkin pie for dessert—succumbing to the influence of another popular song of that summer by Jay & the Techniques. Afterward, I assumed driving duties, and Bert crashed.

It was dark by the time we headed west on Highway 20. Near Arco, consciousness waned, and I resorted to cranking down my window and slapping myself to stay awake. Bert roused to the rush of cold night air and complained, but I explained it was this or death. He chose life and went back to sleep. I considered Wolfman therapy, but that would have been a bridge too far. Near Picabo, I rallied, and the rest of the way was the familiar drive back after our usual night on Silver Creek. I could have done it in my sleep—and almost did. We hit the Sun Valley parking lot near midnight and stumbled to our dorm room.

We fished every night after work and all day on our Wednesdays off. We had Silver Creek almost wholly to ourselves—such was the world of western spring-creek fishing in the mid-1960s.

We were up early the following day, grabbing a quick breakfast in the employees’ cafeteria and then dashing off to work in the famous Sun Valley sunshine. Although we had not prevailed against the mighty Madison, we had endured. And there was a spring in our steps.

As our paths diverged, Bert to his kingdom of the Olympic pool, and I to mine of the tennis courts next door, I called out, “Hey, Bert, Silver Creek tonight?”

“You bet! Do you have any flies?”

Oh, to be 19 again and on the loose in trout country.

This piece originally appeared in the Spring/Summer digital edition of Montana Fly Fishing Magazine. You can check out the article here.