Risk Management

“Living with the immediacy of death helps you sort out your priorities in life. It helps you to live a less trivial life.” —Sogyal Rinpoche, Buddhist teacher

My femur couldn’t be broken. If the thick phonebook of ice had snapped my leg like a concrete dowel, it would’ve made a very distinct sound. “You alright?” my ice-climbing partner Drew called out from his perch 70 feet up the cliff. He’d just smashed loose a plate of ice, and after it skipped down the steep frozen waterfall, all 20 pounds of it took a lucky bounce and connected with my right thigh. The impact threw me backwards, rolling me headfirst down a snow bank where my body ground to a stop just inches from a sheer band of lava rock. “You’re okay, right? An evac would be a real pain in the ass,” he yelled through the darkening canyon, his headlamp shining down like a second moon.

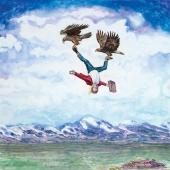

The outdoors are risky, there’s no arguing that. People can—and do—get injured or worse every single year. The mountains demand our utmost respect—and that respect should be paid in the form of good preparation and sound judgment every time you go out, regardless of activity. But really, there’s risk in everything we do, and if safe and sterile is what you’re after, there’s plenty of available real estate in Iowa. No matter what dangerous sport we’re partaking in, Bozemanites know it’s worth the gamble. People here seem to embody the spirit of Lewis & Clark, craving the taste of adventure that only the Rocky Mountains can provide. It’s living surrounded by these jagged peaks and knowing their risks—and succeeding in spite of them—that makes us who were are.

Whether it’s braving avalanche conditions to board the perfect line (page 72), rocketing across a frozen lake in a fiberglass bathtub (62), strapping on a speedflying wing for the first time (86), or ski-touring from Gallatin Canyon to the Madison Valley with a quick summit of Lone Peak (24), it’s this spirit, this collective sense of adventure, that defines us as a town, as a region—hell, as a state. When Montanans head to the hills, we know it might not be safe, but goddamn it’ll be fun, providing experiences and creating friendships that’ll last longer than we know. The mountains have worked their way into our blood, and if you live here long enough—local or transplant—their inherent risks and rewards will pump through your veins too.

Since this was one of the first times he’d swung tools all season, Drew kept giving little impatient tugs on the climbing rope. “You good?” he called down. When the nausea subsided, I stood up in slow motion. My wrist felt sprained, but my knee could bend. My right leg could support my weight—if only just a little. Hobbling the 15 feet back to our bags, I pulled a big loop of rope through my ATC, held it tight with my wet gloves, and called up, “On belay.”