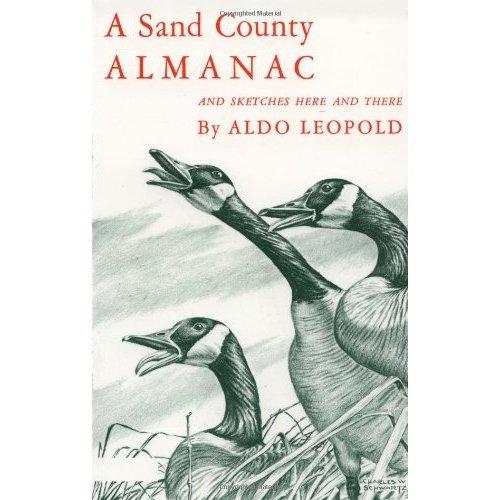

Book: Sand County Almanac

A book for all seasons.

Fifty–one years ago this fall, Oxford University Press published a slim collection of nature essays entitled A Sand County Almanac. Its author was the great forester, ecologist, and first-ever wildlife management professor Aldo Leopold.

Notified of his book’s acceptance a year earlier, the sixty-one-year-old Leopold was jubilant – A Sand County Almanac was, after all, his magnum opus, the consolidated thoughts and theories of a lifetime working, studying, and playing in America’s wilderness. After numerous rejections, his manuscript was finally going to print.

Two days after hearing the good news, Leopold, his wife, and their youngest daughter packed up the car and drove to the family’s 120-acre farm on the Wisconsin River, to spend a week or so in their beloved getaway "shack." It was here that Leopold spent most of his contemplative hours, waking early, strolling the woods, carefully noting the comings and goings of birds, mammals, plants, and seasons. And it was this property – used-up farmland restored to health over the years by Leopold and his family – that became the setting for the vivid, artfully-constructed, poignant nature essays compiled in A Sand County Almanac.

They’d been at the shack only a couple of days when Leopold, sipping his morning coffee on the back porch, spotted smoke from a brush fire near a neighboring farm. He rushed over, strapped a water pump to his back, and began spraying the edges of the fire. His wife worked another part of the fire while their daughter went for help. Eventually the blaze came under control, but Leopold was nowhere to be found. An hour later, a neighbor found him lying on his back, arms folded across his chest, the water pump on the ground beside him. Leopold had suffered a heart attack and died on the spot.

The following autumn A Sand County Almanac hit the shelves. Though it was well received by critics, it sold few copies and garnered only a few meaningless accolades: "charming," "well-written," that sort of thing. This would likely have annoyed Leopold; an entire adult life spent formulating a powerful scientific and philosophical argument for the preservation of wilderness, based on years of probing thought, solid science, and hands-on experience, reduced to "charming"?

And why the lack of popularity for what is now considered a sacred text in the library of environmental ethics? Because Leopold’s ideas were new, foreign, and seemingly impractical. He proposed a radical shift in the nation’s collective ideology, a complete restructuring of American priorities and behavior. He called for a land ethic, which extends the boundaries of human ethics to include not just human relations, but human-earth relations, and which thus "changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such." This idea ran counter to the two-hundred-year-old American doctrine of expansionism and manifest destiny, which saw land as something to be used – and exploited, if necessary – to further man’s progress and economic vitality. This land-as-commodity mentality defined our country and helped promote America from a disordered bundle of colonies to a strong, unified, indisputable world power – and came under direct fire from Leopold. The land has rights too, he declared, and we can no longer simply use it for whatever economic gain we deem convenient at the time. "A thing is right," he wrote, "when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise." Thus our long-standing tradition was terribly misguided.

And so were our current priorities. "Like winds and sunsets," Leopold added, "wild things were taken for granted until progress began to do away with them. Now we face the question whether a still higher ‘standard of living’ is worth its cost in things natural, wild, and free. For us of the minority, the opportunity to see geese is more important than television, and the chance to find a pasque-flower is a right as inalienable as free speech."

However eloquently phrased, these notions were not popular in the American conscience of the late 1940s. People were still reeling from World War II and from the Great Depression; building homes and rebuilding families was a far more immediate concern than upholding the integrity and stability of the wilderness. It would take nearly fifteen years before America was truly ready for A Sand County Almanac, before a few prominent voices would help to resurrect Leopold’s vision. In 1963, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall declared that "if asked to select a single volume which contains a noble elegy for the American earth and a plea for a new land ethic, most of us at Interior would vote for Aldo Leopold’s A Sand County Almanac." A year later, in September of 1964, President Lyndon Johnson made history by signing into law the Wilderness Act, a revolutionary piece of legislation that declared an intent "to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness." The Wilderness Act marked an important step in the evolution of human behavior; for the first time, legislation met ecological philosophy head-on, defining wilderness as "an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." This definition rings of Leopoldian verbiage, and the resemblance would no doubt have pleased him.

Gradually A Sand County Almanac gained popularity. Sales increased steadily throughout the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, and when it went to paperback in the late 1960’s it sold over a million copies in just a few short years. It soon became required reading in colleges and in many government agencies. By 1987 Leopold’s little book, which he initially thought might never find a publisher, had seen over 40 printings. And as the 21st century opens up before us, marking the Almanac’s fifty-first anniversary, Leopold and his land ethic are still present in the hearts and minds of those devoted to wilderness and to the land on which they live. He is a source of inspiration for ecologists, conservationists, wildlife managers, and ordinary citizens everywhere who care about the world and its future more than the thickness of their pocketbooks. He has become, as many predicted he would, a revered wilderness prophet, a sage for all seasons – or, as the great historian and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Wallace Stegner put it, "an American Isaiah."

Look for A Sand County Almanac and other classic nature writings at Country Bookshelf in Bozeman.