The Open Road

A David & Goliath story: How the diminutive Public Land & Water Access Association fights massive monied interests to keep roads, trails, and other access points open for Montana recreationists.

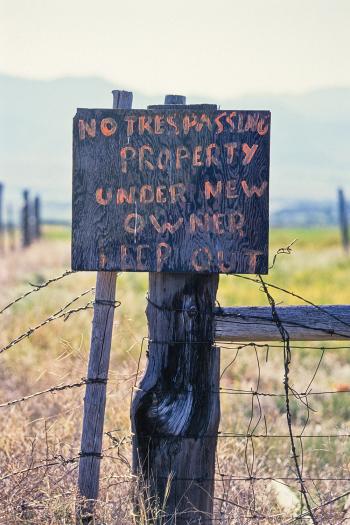

Seyler Lane. Boadle Road. Hughes Creek. Although these Montana place names are all on the map, many Montanans have likely never heard of them, despite their role in our recent history. Each (and this is hardly a comprehensive list) represents the site of a victory in the apparently never-ending battle for the public to be able to enjoy public land and water. In these cases, public ownership of the resource was not in question. The problem was legal access—which had clearly existed historically, only to be denied by selfish landowners intent on building their own private fiefdoms.

These cases represented unlikely court victories by loosely organized, underfunded Montana outdoor recreationists over powerful private interests, and would not have been possible without the Public Land and Water Access Association (PLWA).

Seyler Lane: To Float the Ruby

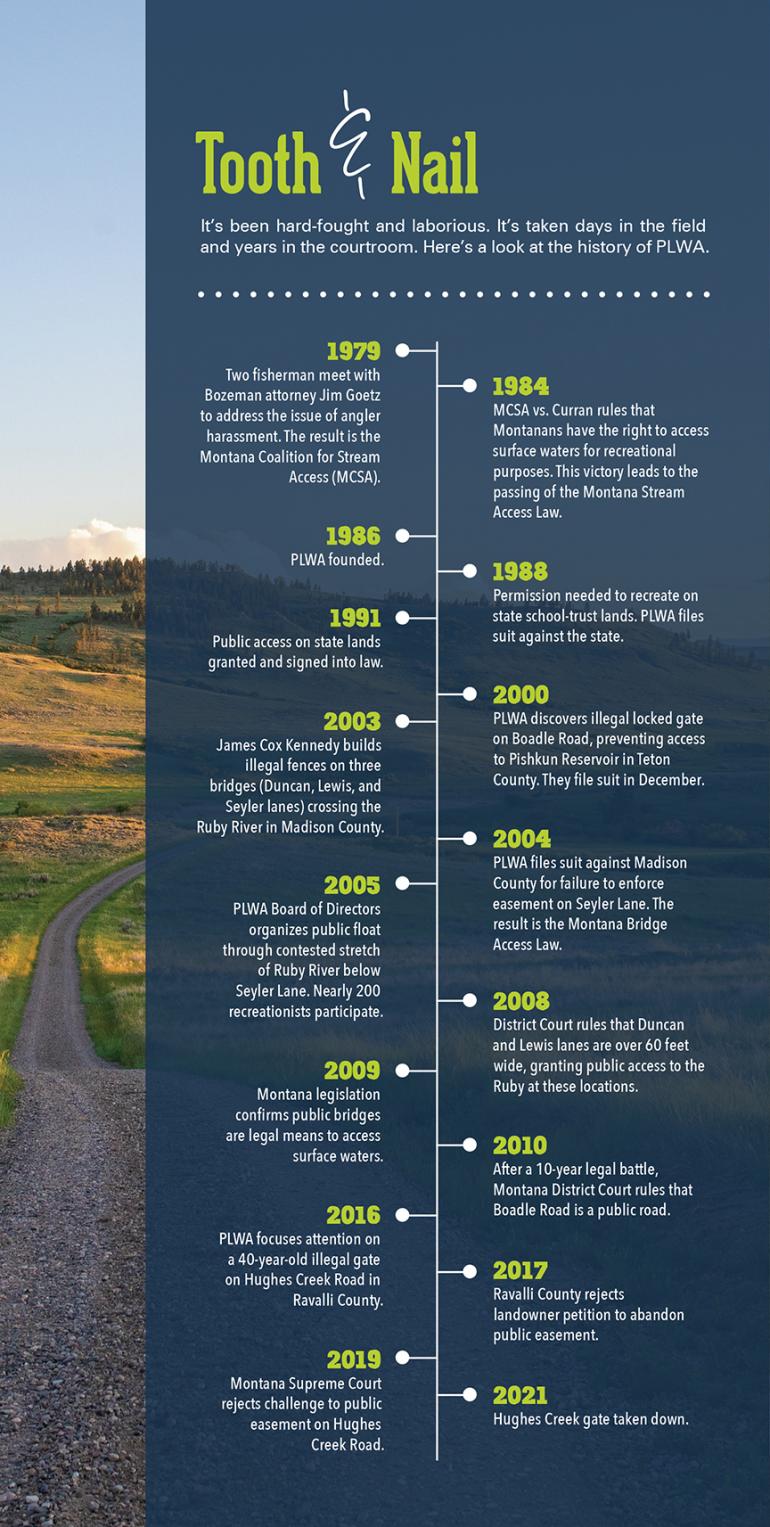

Montana’s long tradition of amicable, cooperative access to its increasingly famous blue-ribbon trout streams began to falter in the 1970s with reports of angler harassment on several western Montana waterways. In 1979, two concerned Butte fishermen met with Bozeman attorney Jim Goetz who suggested they form a statewide organization to address the problem, and the Montana Coalition for Stream Access (MCSA) was the result.

In 1984, MCSA prevailed in two landmark cases heard before the Montana Supreme Court. MCSA v. Curran held that a landowner harassing floaters on the Dearborn River acted improperly. The court ruled that “any surface waters capable of use for recreational purposes are available to the public for such use…” citing the Montana Constitution: “All surface, underground, flood, and atmospheric waters within the boundaries of the state are the property of the state and are subject to appropriation for beneficial use…”

The second 1984 case involved a landowner who had built a fence blocking access to the Beaverhead River and intended to string a cable across the water to block floaters. The court ruled that demonstrating suitability for recreation was sufficient to establish a public right to use the water, with MCSA one of several groups involved in the case.

The following year, the state legislature, with bipartisan support (remember that?), passed what would become one of the West’s most progressive pieces of legislation regarding public right to access: the Montana Stream Access Law. In brief summary, the law holds that the public has a right to access all the state’s perennial waterways between the banks’ mean high-water marks, irrespective of adjacent landownership. Nearly 40 years later, this law provides the legal basis for all of those floaters on Montana streams to enjoy what they’re doing. Since its passage, the Stream Access Law has successfully withstood multiple court challenges.

In 1986, a small group of recreationists created the Public Lands Access Coalition (PLAC) to move the fight beyond the waterline and address the widespread issue of restricted access to public lands. Logically enough, PLAC and MCSA merged and eventually became PLWA.

"The PLWA track record in court has indeed been remarkable, especially given that the opposition has largely been financed by out-of-state uber-wealth while PLWA relies on small donations from Montanans of ordinary means."

The group then turned its attention to the problem of illegal physical barriers to access. By then, Montana demographics were changing rapidly as increasing numbers of wealthy out-of-state interests began buying large tracts of prime recreational property, often accompanied by attempts to keep the public away from nearby lands and waters within the public domain. Historical patterns of use established prescriptive easements at many of these access sites, but some landowners erected physical barriers at bridges and adjoining public rights of way.

In 2000, Montana Attorney-General Joseph Mazurek affirmed that the public “may gain access to streams and rivers using the bridge, its right of way, and abutments.” One would think that would settle the matter, but some new trophy-ranch owners didn’t think they needed to heed Montana law.

None did so more flagrantly or stubbornly than Atlanta billionaire James Cox Kennedy, who had purchased a large ranch along the Ruby River in southwest Montana. Seyler Lane, the road that accesses his ranch, crosses the Ruby, and recreationists had been using the bridge to reach the water for decades, with full support, including an easement, voluntarily provided by the previous owner. In 2003, Kennedy began erecting barbed-wire fences, physical barricades, and even electric wires to impede floaters’ access to the river, creating just the kind of issue PLWA was born to address.

"Now, however, after two decades of legal proceedings, floaters can reach the Ruby at Seyler Lane, thanks to PLWA."

In 2004, PLWA filed suit against Madison County for failing to enforce the easement. The ensuing legal battles took years to resolve and need not be reviewed in detail here. During that interval, the legislature again took bipartisan action and passed the Montana Bridge Access Law, affirming that the public has the right to access the state’s streams and rivers from any public bridge or road easement.

Perhaps inevitably, the case wound up before the Montana Supreme Court in 2013, giving Kennedy and his attorneys an opportunity to reveal their true intentions. They began by asserting that Kennedy owned not just the water, but the streambed below it and the air above. When the clause in the Montana Constitution that establishes public ownership of the state’s waterways was cited in argument, Kennedy’s attorney objected. After listening to his complaint, one incredulous justice asked if he was asking the court to declare the state constitution “unconstitutional.” The answer: “Yes.” Shortly thereafter, the bench asked if their goal was to overturn the Montana Stream Access Law. The answer? Another yes, to the dismay of observers.

All’s well that ends well, however, and in January 2014 the court unanimously rejected the challenge to the Stream Access Law and ruled that the public has a right to access the river from the bridge on Seyler Lane. The court also recognized ranchers’ need to control livestock with fencing and specifically allowed for this. However, it also specified a complex series of steps to be taken when fencing interfered with access and the landowner would not voluntarily alter it to accommodate public interests. Dickering over this provision would delay unimpeded access to the Ruby for several more years. Now, however, after two decades of legal proceedings, floaters can reach the Ruby at Seyler Lane, thanks to PLWA.

Boadle Road: A Bridge Too Far

The persistence some landowners demonstrate in their efforts to keep the public out of public lands can be amazing. If you think Kennedy’s repeated court smack-downs should have taught him his lesson sooner, wait until you read about this one.

In the late 1990s, one Roger Jones, then a Virginia resident, bought a piece of Teton County land near Pishkun Reservoir. A segment of Boadle Road crossed the property. Although recreationists had used the road for years to access the reservoir and the vast Rocky Mountain Front Conservation Area, Jones insisted on having the seller erect gates as part of the purchase agreement.

In the fall of 2000, Great Falls resident and longtime PLWA supporter Jim McDermand set out to hunt ducks on the reservoir, only to run into a gate on a road he had driven for years, and the fight was on. PLWA filed suit later that year, asking the court to affirm the road’s public status and remove all barriers.

From this point on, the story of the court actions becomes long and complicated, and since readers have already been through that once, I’ll spare the details. In sum, over the next 15 years, the landowner kept losing and PLWA kept winning. In all, Jones wound up in the Montana Supreme Court five times.

The geography is complex too, but the salient feature is the Boadle Road Bridge that crosses the Sun River Canal and leads to all the public land on the other side. In 2002, the bridge burned for reasons that apparently had nothing to do with the conflict, and Jones rebuilt it. In a fit of spite following one of those court losses, Jones tore down the bridge on Boadle Road and replaced it with one on his own property in order to have more control over the access.

In 2011, PLWA filed for damages on the grounds that one cannot destroy improvements to a public bridge no matter how they came about. By the time this round wound up in the Supreme Court, PLWA was asking for attorney’s fees and punitive damages, asserting that the landowner had engaged in “tortuous interference.” The court agreed. Awarding attorney fees is unusual, but the court had clearly grown tired of Jones’ futile round-trip visits, despite an 0-for-5 record. In a further irony, as part of the damage awards the court required Jones to pay for replacing the bridge he had torn down.

The bottom line? PLWA won a substantial amount of cash to help fund future battles, and the public can now access Pishkun Reservoir and the wilderness beyond as they always had.

Hughes Creek: Landowners Above the Law

No situation is more frustrating to public land access advocates than wining decisively in court and still being unable to get where you were trying to go. No recent case illustrates this problem better than the dispute over the Hughes Creek Road in Ravalli County.

Built in 1900 to provide access to a mine across Forest Service land, the 12-mile-long road provided recreationists opportunities on thousands of acres of public wildlife habitat for years. In the late 1970s, several local landowners constructed a gate across the road, eliminating all access to the Hughes Creek drainage. In 1982, landowners petitioned to have the county formally abandon its interest in the road. Citing Montana law stating that a county cannot abandon a road if it is the sole access route to an area, the court denied the claim.

During subsequent court actions brought by PLWA and the Ravalli County Fish and Wildlife Association that reached the Montana Supreme Court, Justices repeatedly ruled that the Hughes Creek access was indeed a county road. Since Montana law states that “…When a county road becomes obstructed… the board of county commissioners shall remove the obstruction,” that should have been the end of it. Right?

Wrong. As a preview of the disregard for the rule of law that has since swept the nation, Ravalli County Commissioners refused to act despite multiple court orders. In 2017, the County actually ordered the gate removed, but it wasn’t. Landowners threatened violence against anyone who tried and had contact with out-of-state interests known to use violent means in similar situations elsewhere. In a phone call, the Ravalli County attorney told the PLWA legal team that he would not take further action, because “Removing the gate is a threat to public safety as a result of landowner threats of violence.”

And there stood the gate, denying access to a huge tract of public land, even after two decades of legal decisions declaring that it had to go. PLWA and the local Ravalli County sportsman’s group didn’t quit. On January 14, 2021, their attorney, Devlan Geddes, wrote a detailed letter outlining all the relevant facts and legal opinions to Governor Greg Gianforte. A week later, Ravalli County employees physically removed the gate. The details of the decision-making behind this unconscionably delayed action by Ravalli County remain unclear, but at least they finally got it right and followed the law.

PLWA and its allies needed two decades to accomplish what eventually took place in a matter of hours. I hope the matter is finally settled, but in our current atmosphere of vigilante behavior, one can never be sure.

The story as told thus far makes PLWA and its excellent attorneys at Bozeman’s Goetz, Baldwin & Geddes appear invulnerable. The PLWA track record in court has indeed been remarkable, especially given that the opposition has largely been financed by out-of-state uber-wealth while PLWA relies on small donations from Montanans of ordinary means.

"The persistence some landowners demonstrate in their efforts to keep the public out of public lands can be amazing."

No one can win them all, however. In 2020, the District Court ruled against PLWA in an important case involving Mabee Road, which provided access to a vast swath of public land in the Missouri River Breaks north of Roy. A local outfitter purchased a piece of land that the road runs across for a short distance and gated it, giving his clients exclusive access to one of the best trophy elk herds in the nation. Despite presenting abundant evidence that the road met all the legal requirements for a prescriptive easement, Judge Brenda Gilbert saw the matter differently.

While this piece has devoted a lot of space to court cases, readers should realize that in every instance, litigation only came after multiple attempts to compromise with the adverse party, as is PLWA’s standing policy.

When all is well, taking good fortune for granted is just a part of human nature. It usually takes a threat, real or perceived, to get people motivated. Here in southwest Montana, it is perhaps too easy to settle for what we have: clean air and water, spectacular scenery, and abundant opportunity to enjoy the outdoors, including fishing good enough to draw visiting anglers from around the world.

However, I would ask complacent readers to engage in a brief thought experiment. What would life in Bozeman be like if James Cox Kennedy’s legal team had accomplished its stated goal of overturning the Montana Stream Access Law? Perhaps the legislature would have replaced it with regulations like Wyoming’s. Across the state line to our south, private landowners don’t just control river access. The also own the banks (nevermind that high-water mark) and the streambed. Without landowner permission, floating anglers can’t step out of the boat to play a fish, take a picture, or relieve themselves, and whoever is at the oars can’t even drop anchor. How many anglers are going to travel long distances for an experience like that?

Outdoor recreation has become a cornerstone of our regional economy, and despite my personal concerns about over-crowded rivers, I recognize the importance of those tourist dollars to all of us. Furthermore, our lives would become boring if we didn’t have open access to waterways and public land. That’s the reason most of us live here in the first place.

If the default position were Option A (no change) as it is on most public-land-use proposals, we could all relax and go fishing, but it isn’t. Powerful interests fueled by out-of-state money have demonstrated a consistent pattern of using their resources in the effort to privatize public land and water.

None of us can fight those efforts alone, as the far-sighted people who founded PLWA recognized years ago. The least those of us who enjoy these resources today can do is support the grassroots organizations that have made this possible. The metaphoric battle between David and Goliath shows no signs of ending soon. Visit plwa.org, get informed, and make a donation. Your continued access to public land and water depends on it.