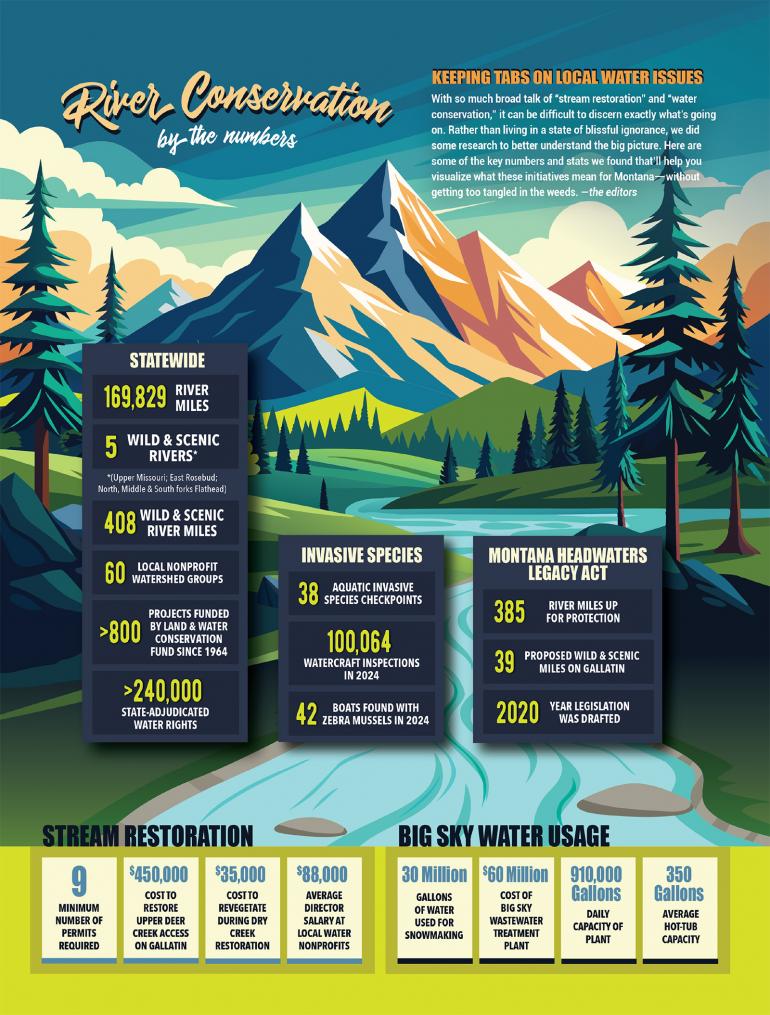

Standing Guard

A roundup of local nonprofits keeping watch over our state’s invaluable waterways.

Montana rivers see a lot of pressure. Every year, swarms of anglers, boaters, and campers descend on our streams from near and far in search of cold water, big fish, and riverside relaxation. What’s more, ranchers divert gobs of water for irrigation, and cities siphon off even more for residential and commercial use. Not to mention all the unclean inflow from water-treatment-plant releases, septic-system seepage, and agricultural runoff. All told, it puts a lot of pressure on our waterways—so much so, that our rivers need help, and lots of it. Thankfully, there are a heaping handful of nonprofits in our state—and more specifically, in southwest Montana—that bring people and resources together in the name of stream conservation. The following is a selection of groups that are worth supporting, with either time or money, or at the very least learning a little more about. Take note, however, that our roundup is not comprehensive. There are plenty of other local groups doing excellent work in the area—this is just a selection of some of our favorites.

STATEWIDE

The following groups operate at the state level. Some are subsets of larger national organizations, while others are Montana-specific. Regardless, they’re all working hard to protect our aquatic resources.

American Rivers

Operating under the belief that clean, abundant water is essential for all life, American Rivers has been a leader in protecting and restoring our nation’s waterways for more than 50 years. Its Northern Rockies regional office in Bozeman looks after our country’s largest collection of pristine, free-flowing rivers, many of which flow through the heart of Greater Yellowstone. Since the office opened in 2009, it has led the charge in securing long-term protections for more than 2,000 miles of rivers across Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming. It was also a leader in the effort to halt the Black Butte Copper Mine from being built in the headwaters of the Smith River. Current local efforts include working to pass federal legislation that would designate new Wild & Scenic Rivers in southwest Montana, with a focus on the Gallatin, Madison, and Yellowstone. To learn more, get involved, or donate, visit americanrivers.org.

Montanans for Healthy Rivers

Made in Montana. That’s the slogan Montanans for Healthy Rivers (MHR) uses to describe the legislation it crafted to protect 384 miles of new Wild & Scenic Rivers in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Championed by former Senator Jon Tester, the Montana Headwaters Legacy Act aimed to permanently protect 20 streams—among them, the Gallatin, Taylor Fork, West Boulder, and the Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone. While our former senator deserved much credit for his role in moving this ambitious bill, the true architects behind it were MHR, an organization that’s earned endorsements from more than 3,400 Montanans and 2,000 Montana business owners. Now that Montana’s congressional delegation has changed, MHR is working with its members to craft a new Wild & Scenic Rivers bill focused on Gallatin, Madison, and Park counties. To get involved, visit healthyriversmt.org.

Montana Freshwater Partners

How can modern-day humans live in harmony with the water around them? Inspired by life in and on the water, Montana Freshwater Partners tackles river stewardship through a lens of coexistence. Based in Livingston, this nonprofit simultaneously works with government organizations, other nonprofits, and the private sector. They pilot a plethora of projects, including a beaver-conservation initiative and a remapping of the channel migration zone on the Yellowstone following the 2022 floods. The group also offers technical expertise on everything from stream and wetland ecology, to fish and wildlife habitat, to watershed planning. They’re involved in a ton of undertakings and believe that their unique position allows them to get things done, creating lasting beneficial impacts for our local waterways. To learn more, check out freshwaterpartners.org.

Montana Rivers

This organization’s founder needs no introduction. Twenty-seven years ago, Joe Gutkoski created a grassroots activism group devoted to enhancing water quality by building statewide consensus around new laws and regulations that protect in-stream flows. Though its creator and conservation legend passed away in 2021, Montana Rivers still advocates and operates with Joe’s unflinching passion. The advocacy group continues to promote the beneficial use of in-stream flows, encourages discussion among all river users, and increases public awareness of the importance of water quality with regards to both wildlife and human health. To become a member or learn more, visit montanariveraction.org.

Trout Unlimited

Southwest Montana waterways are fabled for their trout populations; rivers like the Gallatin and Madison hold over 1,000 fish per mile in certain sections. If you’re an angler who enjoys this inimitable bounty, you owe a large debt of gratitude to Montana Trout Unlimited (MTU). In 1962, a group of impassioned anglers decided to get together and organize. Familiar names like Bud Lilly, Bud Morris, and Dan Bailey created the Montana chapter of Trout Unlimited in 1964 with the mission of conserving and restoring our coldwater fisheries and their watersheds. MTU stays busy advocating for clean water, healthy habitat, and robust flows, doing everything from public education, to working with agencies and private landowners, to defending our rights to stream access. Last summer, they held their annual Youth Conservation Camp on Georgetown Lake, where participants contributed to an active beaver-dam-restoration project, toured a fish hatchery, and expanded their knowledge on fishery management with help from FWP biologists. Check out their latest projects, learn more about the organization, and get involved at montanatu.org.

REGIONAL

These river-conservation groups function at the watershed scale in various drainages around southwest Montana. Their hyper-focus helps get things done quickly, often with buy-in from the entire community.

Madison River Foundation

You know that local river that hosts tens of thousands of visitors every year? Between tube floats, fishing trips, and whitewater chasers, the Madison has its hands full. And with such strong recreational use comes the need for a strong team of people to protect it. Since 2002, the Madison River Foundation (MRF) has taken the reins in protecting the Madison and its tributaries, all while taking into account various river users, ranging from guide services to ranchers. The organization’s work is intended to bring people together to the mutual benefit of humans, wildlife, and the river itself. MRF spearheads restoration collaborations among private landowners, including the O’Dell Creek Headwaters Project, which became one of the largest wetland restorations in all of Montana, transforming dried-up ditches back into free-flowing streams. From constructing beaver-dam analogs to stabilizing erosion and incorporating local students into monitoring projects, MFR has no shortage of ways to get involved. Learn more at madisonriverfoundation.org.

Gallatin Watershed Council

The Gallatin watershed begins in Yellowstone and covers almost 1.2 million acres throughout southwest Montana. In the early ’90s, a varied group of working professionals got together with a common goal: to protect the watershed. They brought the Gallatin Watershed Council (GWC) to life in 2004, and the organization now uses education and collaboration as conservation tools, aimed at rebuilding and preserving the watershed while considering viewpoints from all natural-resource users. From stream and shore clean-ups to tree-planting and fuels-reduction projects, GWC works to restore and maintain. For those looking to lend a hand, GWC hosts a stream-monitoring program—Gallatin Stream Teams—and works with the City of Bozeman to plant trees and shrubs to keep the town green among fast-paced urban development. When walking by local water sources, such as Bozeman Creek, keep an eye for their interpretive signage, too. Find more opportunities at gallatinwatershedcouncil.org.

Gallatin River Task Force

Upkeeping rivers, especially those that host critically-acclaimed films and thousands of tourists, takes a village—or in this case, a task force. A group of volunteers banded together in 2000 to sample the Gallatin River at various spots along its upper sections, and the Gallatin River Task Force (GRTF) began. In 2012, GRTF initiated its Upper Gallatin Restoration Plan to protect the river’s water quality, habitat conditions, and resilience against climate change. Recently, GRTF completed a large restoration project at the Greek Creek campground in partnership with the Custer-Gallatin National Forest, in which they rebuilt an eroding streambank, planted willows, constructed beaver dam analogs, and installed a rock terrace to guide people to the river. To learn more, donate, or find a volunteer opportunity, head to gallatinrivertaskforce.org.

Upper Missouri Waterkeeper

Conflicts over water can divide Montanans, but for Upper Missouri Waterkeeper, water is something that should bring us together. Waterkeeper is an advocacy group that protects the public’s right to fishable, swimmable, drinkable water in the Upper Missouri River Basin—a region of 25,000 square miles that includes the main stem of the Missouri from its source to Fort Benton, as well as tributaries such as the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Gallatin rivers. The group regularly conducts water-quality patrols to detect pollution issues, such as unpermitted land use near waterways, improper agricultural practices, and unsanctioned pollution discharges. Waterkeeper emphasizes enforcement of bedrock environmental laws and science-based solutions to some of the most challenging water-resource issues confronting Montana. The organization has successfully stopped the rollback of protective water-quality standards, and secured court victories enshrining the public’s right to meaningful participation in the rulemaking process. They’ve also helped the Big Hole River Foundation launch a water-quality-monitoring program, empowered citizens in stopping the industrial-scale Madison Food Park Slaughterhouse in Great Falls, and worked with the Gallatin River Task Force to improve wastewater-pollution control in the upper Gallatin. To learn more, visit uppermissouriwaterkeeper.org.

Big Hole Watershed Committee

The Big Hole River, a tributary of the Jefferson, is nestled in one of the more remote areas of southwest Montana. Surrounded by a large portion of ranchland, the river is significantly less developed than other nearby watersheds. Still, in 1994, a group of six ranchers saw problems arising on the Big Hole, such as drought and a threatened arctic grayling population. Rather than sitting around and complaining, they wrote a letter to the governor asking for assistance in forming a committee to deal with these arising issues. Thus, the Big Hole Watershed Committee was born. “We bring partners, landowners, and funding together to improve fish passage, fix run-down irrigation infrastructure, rebuild streams and wetlands, stop upland erosion, and deter wildlife depredation of stock with our range-rider and carcass-compost services,” says director Pedro Marques. The committee prioritizes ideas that serve the greater good, fostering a sense of consensus among ranching, utility, sportsmen, tourist, outfitter, conservation, and government groups. Every year, the organization works on about 15 projects across the basin, keeping the river prosperous for years to come. Learn more or contribute to their Big Hole Conservation Fund at bhwc.org.

Big Hole River Foundation

Also operating in the Big Hole watershed is the Big Hole River Foundation (BHRF). In 2020, the organization embarked on a long-term water-quality-monitoring program—the only one of its kind on the Big Hole. The program collects data at ten sites, spanning 150 miles of river, each year from April through October. The foundation, a nonprofit founded in 1988, intends to use the data as the basis for future conservation work on the 2,800-square-mile watershed—which has faced increasing threats in recent years. Those include nutrient pollution, warming temperatures, and residential development—to name a few—and studies show that its once-thriving trout populations are in decline. In 2023, brown and rainbow trout numbers were at their lowest since 1969. The BHRF aims to use the best available science to address these declines, as well as anticipate and prevent those that might arise in the future. To learn more about the organization and its programs, visit bhrf.org.

HONORABLE MENTION

While on-the-ground work is essential in protecting and restoring our waterways, there are the legal and political components as well. Most of the groups mentioned in this article are involved on all three fronts, however one local organization takes things a step further. Here are the details on this outlier of a nonprofit.

Cottonwood Environmental Law

You know the expression: pick your battles. Well, John Meyer doesn’t. If you recognize the name, it might be from the ballot last November. When not campaigning for city mayor (though his run was unsuccessful), Meyer heads up a nonprofit law firm, Cottonwood Environmental Law, where he’s not afraid to seek out cases that others shy away from. Between prosecuting the Yellowstone Club for polluting the Gallatin, suing the Montana Department of Environmental Quality for not doing its job, and going after Big Sky for leaky sewage ponds, Cottonwood has its hands full. The staff also aren’t afraid to get a little dirty. Last year, Meyer was charged with criminal trespass while watching a contractor collect water samples—below the high-water mark—on a tributary of the Gallatin in the Yellowstone Club. The charges were later dropped, but the whole situation was a testament to Meyer’s commitment to the cause. Now, he’s making plans (pre-approved by a federal court) to place dye in a YC golf course pond to determine if it’s draining treated sewage water into the Gallatin. Also on the horizon, a federal jury trial will decide whether Big Sky Resort violated the Clean Water Act by over-irrigating its golf course in November. Ultimately, Cottonwood’s end goal is to stop all luxury development in Big Sky. It’s a lofty ambition, to say the least, but as the expression goes: shoot for the moon. That’s one that John Meyer does get behind. To get involved—or better yet, donate, as Cottonwood’s legal team is a one-man band—visit cottonwoodlaw.org.