River in Search of Resolution

In the ongoing battle for access on the Madison River, multiple interests clash—and there appears to be no resolution in sight.

The Madison River and I go back a long way. When I was a kid back in the 1950s, my father and I would launch our canoe somewhere between Quake Lake and Ennis and fish our way downstream to the next convenient takeout. A canoe may not be the ideal craft with which to navigate that long obstacle-course of rocks, but McKenzie River driftboats had yet to flood Montana waters and a canoe was what we had. Back then, encounters with other anglers were predictably both rare and pleasant.

Years passed. I made my home in central Montana, a five-hour drive from the Madison, but I still made the trip several times every summer, despite having excellent trout fishing closer to home. I saw more anglers than I had 30 years prior, but the gradual increase in company did not compromise the fishing or my enjoyment of the river. Then, sometime around two decades ago, the ambience changed. Parking areas and boat ramps became packed, and sometimes people were rude. While floating, I never seemed to be out of sight of a half-dozen driftboats. The fish were smaller and farther between. The Madison I once loved seemed to be dying before my eyes. Now I haven’t been back in a decade.

These observations are not just the grumblings of a grouchy old-timer. Objective data back them up. A 2019 survey by the Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) showed fish numbers at a 20-year low and a confirmed decrease in the average size of trout commensurate with an increase in total angler-days from around 60,000 in 1985 to over 200,000. While the biological changes were almost certainly multi-factorial (including drought, increased water temperature, and whirling disease, to name three likely culprits), increased fishing pressure likely played a role as well, even though the vast majority of Madison River anglers release the fish they catch. One can debate the mortality rate among released trout, but it certainly isn’t zero, and one study estimated that the average Madison trout was getting caught four to five times during its life.

However, my declining opinion of the Madison fishery wasn’t all about fish biology. The experience on the river just wasn’t as enjoyable as it had once been. I was hardly alone in this opinion, as confirmed by angler-satisfaction surveys conducted by FWP. The level of dissatisfaction and outright anger documented in these studies convinced the agency that they needed to intervene.

FWP and the state Fish & Wildlife Commission faced a daunting task from the start: address the needs of various stakeholders whose interests often conflicted. These differences generally broke down along three classifications of users: recreational anglers vs. commercial guides; residents vs. nonresidents; and floaters vs. shore-based anglers.

Examination of the data revealed a striking increase in commercial activity. In 2008, 6,653 guided fishing days took place on the Madison. By 2019, that number had more than doubled, to 13,909. Increased utilization by nonresident anglers mirrored the increase in commercial outfitting. A 2017 FWP survey showed that 69 percent of the anglers on the river came from out of state. Resentment by resident recreational anglers was perhaps inevitable.

A 2019 survey by the Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks (FWP) showed fish numbers at a 20-year low and a confirmed decrease in the average size of trout commensurate with an increase in total angler-days from around 60,000 in 1985 to over 200,000.

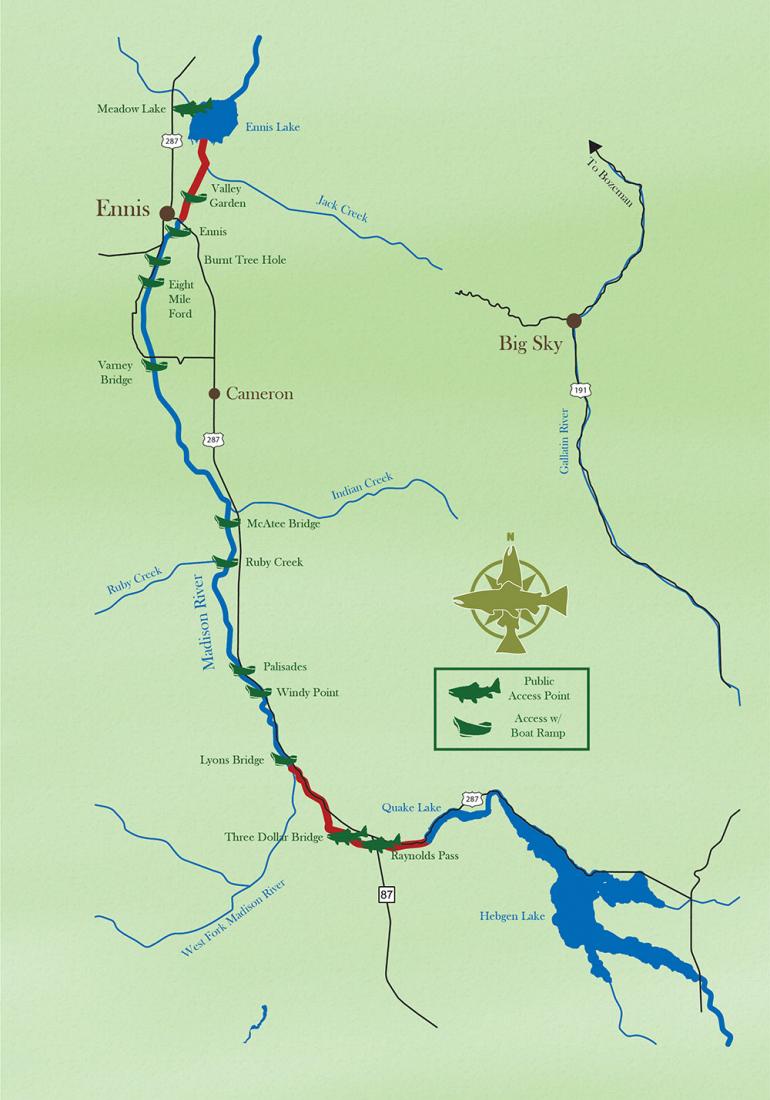

Attempts to address these conflicts by regulatory changes weren’t exactly new. As far back as 1967, FWP enacted float-fishing restrictions on rotating sections of the river, and in 1988, fishing from a boat on the upper Madison was restricted to the section between Lyons Bridge and Ennis Bridge. In 2012, FWP organized the Madison River Citizen’s Advisory Committee (MCAC) to explore compromises and potential solutions among the diverse group of affected parties: local recreational anglers, commercial guides, landowners, and local business interests. (Economic studies showed that Madison River angling generated $150 million annually for the regional economy at the time.)

Most of what came from the MCAC fell into the “feel good” category (preserving the health of the fishery, education, more study), but it did recommend that an increase in user numbers by more than 10 percent, or a drop in angler satisfaction below 80 percent for two consecutive years, should trigger regulatory action, with details unspecified. The MCAC eventually disbanded after failing to reach any consensus on regulation.

In 2018, FWP issued a Recreation Management Plan for the Madison, with two alternative courses of action proposed for the upper Madison (from Quake Lake to Ennis Lake).

The first option, as is usually the case, was “No Action.” The “Preferred Alternative” included capping guide numbers at current levels, eliminating commercial use on rotating sections of the river, and prohibiting the use of a boat not only to fish from (which was already prohibited), but also to gain fishing access in designated walk/wade areas. The Commission declined to release this document and asked FWP to create another committee to study the issue, making the “No Action” option a winner by default.

In 2019, FWP defined three long-term goals for Madison River management: preserve the fishery, reduce user conflict, and sustain ecological and economical value. The first and third of these seemed obvious and produced little dispute, but the second was another matter. Two contentious proposals emerged. 1. Reduce angling pressure by prohibiting fishing from boats in certain parts of the river on certain days. Since the vast majority of guided fishing takes place from boats, this concept was opposed by outfitting interests and supported by recreational anglers. 2. Reduce crowding by maintaining or expanding “walk/wade” areas inaccessible by boat. Again, commercial interests opposed this concept while recreational anglers supported it.

In 2008, 6,653 guided fishing days took place on the Madison. By 2019, that number had more than doubled, to 13,909.

FWP conducted a survey to gauge public response—over 8,000 people weighed in. The questions were open-ended. Of those Montana residents who addressed crowding, 54 percent rated the number of boat anglers between Lyons Bridge and Ennis Bridge as “unacceptable” or “very unacceptable.”

In late 2020, the Commission proposed regulatory changes with regard to the survey responses. Specifically:

1. From June 15 – September 30, guided trips would be prohibited on Sundays between Lyons Bridge Fishing Access Site (FAS) and the Palisades Day Use Area. On Saturdays, they would be prohibited between Raynolds FAS and Lyons Bridge. These “rest/rotation” regulations were scheduled for review in 2023.

2. Walk/wade concerns were ostensibly addressed by continuing to prohibit fishing from a boat between the Ennis FAS and Ennis Lake and between Quake Lake and Raynolds—except that fishing from a boat would be allowed between Raynolds and Lyons Bridge on Saturdays and Sundays.

3. Another committee was formed to replace the defunct MCAC. Created by the Commission, the 12 members of the Madison River Work Group (MRWG) included diverse stakeholders similar to the old MCAC, with additional representation from the Commission and the Bureau of Land Management, which has issued Madison River Special Use Permits to outfitters since 2007.

The Commission also charged this group with producing recommendations regarding permits for new outfitters and consequences of violations. After a period of public comment which again revealed strong support, the Commission voted to adopt these rules.

The new regulations were scheduled to go into effect at the beginning of 2022. However, in September 2021, the MRWG formally recommended that the Commission repeal the walk/wade and rest/rotation actions, citing what it claimed was strong opposition to the new rules. This aroused a swift response from groups representing resident anglers. A coalition of local sportsman’s groups consisting of the George Grant Chapter of Trout Unlimited, the Skyline Sportsmen, and the Anaconda Sportsmen submitted a petition protesting the repeal effort, criticizing lack of transparency by the MRWG and disputing that group’s assertion that the new regulations lacked public support. Representing the guide faction, FOAM (Fishing Outfitters Association of Montana) continued to oppose the rest/rotation regulations.

In October 2021, the Commission voted to repeal its previously approved rest/rotation regulations. Because of a legal technicality, it voted to amend rather than repeal walk/wade provisions. These actions were then submitted for public comment in accordance with state policy.

In December 2021, the Commission affirmed its decision to repeal the rest/rotation rules it had previously created. (The composition of the board that repealed these provisions was very different from the one that created them.) The Commission amended the walk/wade regulation rather than repealing it, because of difficulties in the language through which outright repeal would have ended all walk/wade sections. Thus, the walk/wade sections remained what they had been for years: Quake Lake to Lyons Bridge, and Ennis Bridge to Ennis Lake.

The resource cannot withstand indefinite expansion by all user groups.

During the call-in segment of the meeting when this decision was made, Steve Luebeck of the Sportsmen’s Coalition challenged the contention that public comment overwhelmingly favored repeal. The commissioners responded to this protest with deafening silence. Luebeck later told me: “Every time the Commission has asked for public input on the proposed rest/rotation or walk/wade rules, the public expressed overwhelming support. Yet, when proposing to repeal these rules, this commission has claimed the opposite. At the last meeting, there was no discussion of these results.”

In order to hear from both sides of the conflict, I spoke with Brant Oswald, a local guide and senior adviser to FOAM. He pointed out that FOAM supports the proposed cap on guide numbers, thus identifying at least one point upon which there seems to be agreement. He also raised concerns about the law of unintended consequences. Closing certain sections of the Madison to fishing from boats would likely just move those guides and anglers to an open stretch of the Madison or to other nearby streams (which are starting to see crowding problems of their own).

He also reminded me that, as most local residents realize, the population of the Bozeman area is growing at an unprecedented rate. In his view, rest/rotation regulations will do little or nothing to reduce crowding on the river due to this factor.

As of this writing, that is where matters stand. Previously enacted rest/rotation regulations on the upper Madison will not go into effect in 2022 as previously scheduled.

No matter what happens next, the fundamental conflicts will likely endure. Two of the key stakeholders—resident recreational anglers and guides with nonresident clients—hold views that seem largely incompatible. Resolution will require significant concession by both parties, which at least thus far has not been forthcoming.

As a resident recreational angler myself, my personal views should be obvious, although I have tried to report the facts as objectively as possible. However, I have difficulty trusting a politically appointed committee that repeatedly disregards the opinion of Montanans whose interests it is supposed to represent. In a range of matters (highlighted by its recent proposed controversial changes to big-game management), the Commission has shown obvious bias toward commercial interests and wealthy out-of-state landowners while throwing Montana residents of ordinary means under the bus. At some point, those of us who live here—the ones who pay state taxes and take care of the place when it’s 20 below zero—will inevitably say enough.

In October 2021, the Commission voted to repeal its previously approved rest/rotation regulations.

I am not inherently biased against guides. (In fact, I’ve been one, in another state and for a different quarry.) However, Montana’s fly-fishing industry (a deliberate word choice) as it exists today is a phenomenon that has only recently outgrown its marginal historical importance to the economy of the region. Fortunately, all parties seem to agree on capping guide numbers on the Madison.

The resource cannot withstand indefinite expansion by all user groups, we must move toward a compromise that everyone can live with—even though no one gets everything they want. Since negotiations currently appear deadlocked, we need some new ideas and I’d like to propose one, based on successful approaches to similar problems in other states.

Cap guide permits at current levels. Grandfather in all currently active guides and create a sunset provision that will invalidate the permit unless it is sold. Retiring guides would have the option of selling their permit back to the state, to another guide, or to parties that wish to reduce the number of guides on the river. (As a matter of principle, I have reservations about monetizing the resource, but variations of this model have worked well in other states and the total number of guides on the river would not increase.) Require nonresident anglers on the river to purchase a Madison River permit structured along the lines of current nonresident fishing-license options: valid for various lengths of time ranging from one day to an entire season, priced accordingly. Earmark this revenue for FWP and use it to buy back existing guide permits from willing sellers.

And while we’re at it, demand a Fish & Wildlife Commission that respects the interests of ordinary Montana citizens.