Bangtail Boondoggle

Lawsuits and languish ten miles from home.

Nestled a few bends up Bridger Canyon, rising east from Hwy. 86, is a mosaic of rolling forest that has provided recreation and solitude to Bozemanites for a long time. Stretch the term “Bozemanite” as far back as you feel is relevant, but for decades, the Bangtails have served our community as a close-to-home outdoor haven. While the hills are often overshadowed by their sister range across the highway, the network of timbered draws and old clearcuts is more likely to attract roughshod woodsmen than it is Gore-Tex–bedecked mountain athletes. Generally speaking, that is. Of course, the small range boasts the start and finish of what some locals would call the Gallatin Valley’s most iconic mountain bike ride. The 23-mile point-to-point, known as the Bangtail Divide, was established in 2003 and is now on the bucket list of every Bozeman-area biker and trail runner. This route sees thousands of users every year, everyone from day-hikers to motorheads. Off the trail, wooded drainages and open meadows have proved important wildlife habitat and successful hunting grounds for generations.

When Houston, Texas-based Lazy J Ranches and the Brask family bought the property on Stone Creek, they decided they didn’t much care for keeping with the neighborly spirit.

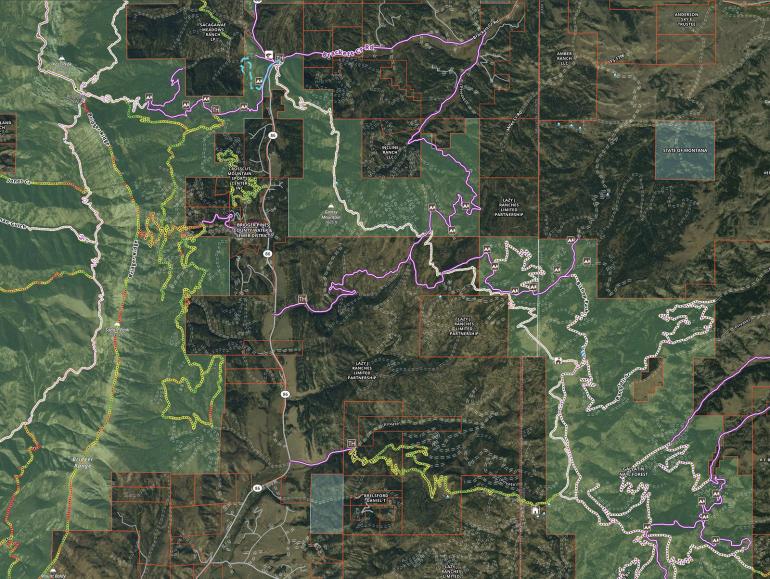

A product of the 1870s railroad grants, the mixed-ownership Bangtails were divided up into isolated square-mile sections. If you look at an ownership map pre-1990, it appears as a checkerboard. Succeeding the railroad’s title to the land was Plum Creek Timber, who eventually sold it to Big Sky Lumber (BSL). In effort to amalgamate both public and private lands in the greater Bozeman region, the Forest Service struck a deal in 1998, trading 31,000 acres of federal land for 55,000 acres of BSL land. The swap, known as the Gallatin Consolidation Act, united a swath of National Forest in Gallatin Canyon at the expense of combining large parcels of BSL land in the Bangtails and other nearby areas, including Big Sky (BSL front-man Tim Blixseth used the acreage he gained in this trade to develop what is now the Yellowstone Club).

As this land in the Bangtails changed hands through the years, one thing that remained in one form or another was access. When Plum Creek Timber owned it, the company didn’t mind the public venturing onto their ground to hunt or hike. They even had designated areas where people could go to cut firewood. Eventually, RY Timber bought it from BSL, and subsequently enlisted the 5,550 acres in a Block Management Area (BMA), making it well-known that the private land was available to the community. But when Houston, Texas-based Lazy J Ranches and the Brask family bought the property, they decided they didn’t much care for keeping with the neighborly spirit. In the fall of 2019, the welcoming green BMA boxes were replaced with “No Trespassing” signs. A couple years later, the Brasks took it a step further.

In 2021, after the Bridger Foothills Fire blackened the canyon, logging companies went to work cleaning up the mess. The Brasks directed a contracted logger to move slash piles several thousands of feet away from the work site to barricade the edges of Stone Creek Road, just past the highway turnoff. The move effectively blocked a de facto public parking area, commonly used by mountain bikers riding the divide trail, or cross-country skiers heading up the road in winter. Thing is, Stone Creek Road has a “perfected” easement on it, meaning it’s agreed in writing that the public has access. It’s been that way since 1979, when the agreement was signed with the Forest Service declaring a 60-foot public right of way along the entire length of the road—from the highway turnoff to the official parking lot about a mile farther.

Unfortunately, the Brasks aren’t the only landowner seeking to close public access in the area.

Shortly after the slash-pile stunt, the ranch was fined by the Forest Service and the logs were removed. But this wouldn’t be his last attempt at limiting access in the Bangtails. DJ Brask and his attorney Brian Gallik are set on the idea that the easement only allows for passage through to public lands—not parking. This past fall, he filed a lawsuit with the Forest Service claiming that the public has abused the agreed-upon terms by parking on the road. Additionally, he’s made claims that the original language of the easement allows him to install a gate on Stone Creek, pointing out that the Forest Service should pay for it. Good thing for the public, however, it’s made clear on page one of the easement that “the grantee (USFS) shall not construct any fence within the specified right of way.”

Unfortunately, the Brasks aren’t the only landowner seeking to close public access in the area. There are currently six ways for the public to access National Forest in the Bangtails. The Brask family owns land surrounding two of them (Stone Creek and Olson Creek). A third, up Skunk Creek Road on the north side, has a seasonal gate closure at the entrance. Recently, a new landowner, his identity concealed by the name Incline Ranch LLC, has been plowing snowpiles to block parking near the gate. It’s also been reported that said landowner has used a megaphone to harass recreationists. Under the easement in Skunk Creek, documented in 1959, the public was granted a right-of-way of 66 feet for up to 48 hours. Incline Ranch has challenged this in court, filing a complaint against the Forest Service in November.

Should these landowners get the rulings they’re arguing for—that easements only allow for entry and exit onto public lands—it could set a scary precedent for the future. Parking on a public road surrounded by private land would no longer be legal. Which, in the case of Skunk Creek during the road closure, would result in the loss of that access point altogether.

While the Bangtail boondoggle is happening real-time, right in our backyard, it’s a perfect microcosm of what’s taking place all over the West. This is not a new story. If anything, it’s gotten to the point where learning about threats to public access is just another day in the life—a life that so many of us have taken for granted. A life that is changing in ways both slow and rapid, to a form that might never be the same again.

Stay tuned for the outcomes of both the Stone Creek and Skunk Creek cases, and get involved with more land-access issues at plwa.org.