On Affluence and Effluent

“A thing is right only when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the community; and the community includes the soil, water, flora and fauna, as well as the people. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

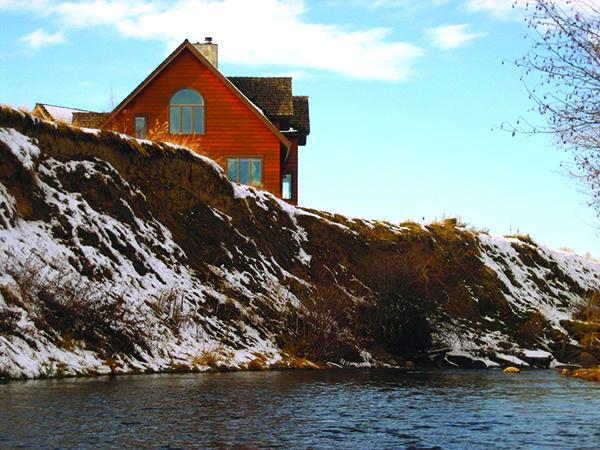

Throughout its history, the Gallatin River has carved a beautiful, rugged canyon, and its pristine waters have the slaked thirsts of, given sustenance to, and coursed through the veins of both the indigenous and pioneer communities of southwest Montana for generations. It has moved logs for local businessmen and provided unending opportunities for fishing and other recreational pursuits. It is as much or more a part of the Big Sky community than any other member. So when it came time to grant the Gallatin protection from declining water quality, in the form of the Outstanding Resource Water (ORW) designation, most folks signing American Wildlands’ original petition believed that this was a simple and sound solution, ensuring that both current residents and future generations would be able to enjoy the Gallatin River as it is today: clean, beautiful, and full of trout. But this simple concept has now become a local centerpiece for the larger national debate between conservationists and developers as they wrangle to control the fate of the New West. Our current choices are some of the last important decisions that can ever be made regarding land use and water quality in the Greater Yellowstone Area, yet conservation still falls short in the face of the tantalizing “Immediate Economic Benefit” that has been the driving force behind the campaign to stop or delay the process of ORW designation.

At a Public Hearing concerning the ORW last October, I listened to speakers from American Wildlands, the Greater Yellowstone Coalition, and several other environmentally responsible organizations speak on behalf of the Gallatin. Their efforts are to be applauded, but the sad truth is that they were completely outgunned by a silver-tongued lawyer, a local politician, and a nicely orchestrated string of disadvantaged canyon locals, frightened faux-blue-collar workers, and the rest of the usual suspects that Big Development tends to round up for these sordid affairs.

With only vague and abstract ways of quantifying the actual net worth of a pristine river and having to rely on projections and theories as a basis for averting possible negative outcomes, environmentalists found themselves at a great disadvantage when compared with opposing testimony virtually guaranteeing the simultaneous destruction of both the Big Sky economy and the working-class families of the Gallatin Valley. In the end, I was left wondering if ORW status would ever be able to get through the legislative process intact.

That question was answered on January 24, 2007 when I learned that the ORW process had been officially put on hold while environmentalists and conservationists work hand in hand with developers, forging an alliance that will ensure that the Gallatin River's water quality will remain as good, better, or good enough to achieve maximum build-out. The outcome of course depends on what this new alliance comes up with over the next several months of brainstorming, negotiation, and development. I am doing my best to remain optimistic about the future of the Gallatin, but “environmentally friendly development” in Big Sky sounds more like a punchline than a way to protect this river, and you can be sure that when the price tag for good or better water quality shows up, it will be few indeed who step forward to help pick up the tab.

But what has really struck me throughout this ORW process is this: how desperately we as a society have become attached to near-sighted economic gain. The Gallatin Canyon resident who already had much more than he could ever need was more concerned with lining his pockets than protecting the waterway on which he has lived a good portion of his life. A local raft company, whose very lifeblood is tied inextricably to the lifeblood of the Gallatin Canyon, was more concerned with the most cost-effective septic solution for a future restoration project than giving back to the river that had given it so much. Even the fine folks fighting for the protection of the mighty Gallatin were forced to speak, at considerable disadvantage, on the need for preservation in strictly economic terms.

This insatiable lust for all things superficial and unnecessary has become so widely accepted by all of us that the concept of protection for a river that we all love pales in comparison to the idea of building the maximum number of luxury second-homes for society’s upper crust. I believe that we have reached a point where we simply must face what is now a glaring and obvious truth: We, as a society, as a people, are no longer “sustainable.” Not like this. If we choose not to recognize, at this critical juncture in time, the need for sacrifice and self-restraint in our very own backyard, it will not be some distant bloodline that shakes its head in contempt at our gluttonous ways, but our children and grandchildren who will ask how we could shamelessly sell the well-to-do on the phrase “Last Best Place” while simultaneously ensuring that it could no longer be.

For now, the best that a concerned citizen can do is to keep a close eye on the progress being made and to contribute time, skills, and energy. There are several good sources of information for staying up to date on this issue. Try the American Wildlands website (wildlands.org) or the Gallatin River Task Force site (gallatinrivertaskforce.org).