Runners High

Lessons from a mountain marathon.

Twelve years ago, when Sam Korsmoe was brainstorming ways to bring people to Ennis, a “crazy idea” entered his head: to hold an annual road marathon above 9,000 feet. He immediately wondered if he might be losing his mind. Marathon tourism was popular enough, but most runners avoided high elevations. Besides, what did he know—he’d never even run a marathon himself. Just how many people would rise to such a challenge?

But Sam saw it through anyway, and the race was a success. As it turned out, people all over the country were happy to ditch city marathons in favor of more difficult terrain. Each year the attendance grew, runners came from farther away, and eventually the race started selling out. Sam’s crazy idea—instinct, really—had been spot-on, and he quickly started adding more races to the lineup in Ennis.

So what started out as an oddball stratagem for economic development soon culminated in the Greater Yellowstone Adventure Series (GYAS)—a set of seven endurance events, involving running, biking, and swimming, and boasting some of the toughest and most scenic terrain in the country.

Sam Korsmoe (left) and his son.

Sam Korsmoe (left) and his son.

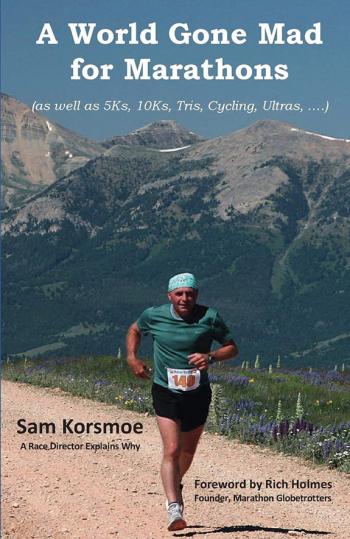

Sam’s recent book, A World Gone Mad for Marathons, attempts to uncover the cause of the boom in organized endurance races. It also explores what drives certain people to pursue such challenges. Sam weaves all this together, including his own philosophies on running, by introducing us to ten different endurance runners. Each athlete’s story revolves around a certain theme that defines some aspect of the runner mentality.

"When I started writing this book, the main questions I asked were, 'What the hell’s going on? How do I tell this story?'" Sam explains. And another, equally important consideration: "'How do I pull the pieces together in a way that addresses the events and mentality?'" As it happened, the running community that Sam had cultivated in southwest Montana provided the ten voices he needed to answer these questions.

When asked if he found any parallels between writing a book and running a marathon, Sam says, "I definitely referred to it as a marathon journey. You must stick with it, keep going, and not stop. Every day you wake up and get to work. You can’t shirk your writing responsibility."

A native of Montana, Sam began a life of international travel and Asian-culture immersion in 1985. His work history includes being a Peace Corps volunteer, English teacher, teacher trainer, business journalist, and entrepreneur. Upon returning to Montana in 2004, he became the executive director of the Madison County Economic Development Council, and was tasked with increasing the amount of capital in the county’s low-income communities.

"This whole race series is based on what I call ‘economic gardening’—it means to take care of what you have and grow it." He describes the concept by implying if you have a factory, it’s more efficient to add a job than to create a new factory. Part of that premise involves using the features you have that no one else has. "Ennis just happened to have a road at 9,000 feet in elevation in the Gravelly Range. All it took was one person saying, 'Let’s do a marathon on it!'" This led to the inaugural Madison Marathon on Labor Day weekend in 2008.

While the book project began as an attempt to discover why so many people around the world were seeking out difficult endurance challenges, it soon morphed into a means to share friendship, affinity, vulnerability, and differences. "There are a lot of angry people in this country," Sam explains. "One of the things I learned in researching this book is that people really need to join a race and go for a run. You’ll meet other people, find your community, and be able to share your stories." And with that, goes the theory, much of that anger—which is rooted in isolation and disconnection—will disappear.

Whether Sam found the community or the community found him, something special began forming in southwest Montana. The popularity of the Madison Marathon led to the subsequent additions of the Madison Duathlon and Triathlon in 2012 (completing all three earns you immortal fame and glory as a TBA—Total Bad Ass). Three years later, Sam created Montana’s only double marathon by adding the Big Sky Marathon the day after the Madison, as well bringing the existing Water to Whisky 5k fun run under the GYAS umbrella. A 57-mile bike ride, aptly named the Tour de Gravelly, was added in 2017 and 2020 will see the addition of an ultra-distance race that gives runners the option of running from downtown Ennis into the mountains, or vice versa.

All these additions were instinctive and spontaneous, in keeping with the spirit of the first Madison Marathon. "It grew into something I didn’t necessarily expect," Sam confesses. "The idea of adding more races, a trifecta, doing something called TBA—all that was pulled out of my ass."

At a private release party, five of the book’s featured athletes—Jon Goodman, Jenny Whitaker, Nikki Kimball, Eduardo Garcia, and Lynda Andros-Clay—sit at a head table and share their experiences, insights, and observations with the other guests.

One recurring topic is attitude. While endurance events have spiked in the 21st Century, so have absurd amounts of competition, egotistical righteousness, and commodification of major races. The GYAS counters these issues by making events so ruthlessly difficult that many races promise first-time entrants a PW—Personal Worst (a sardonic play on a common acronym among runners: PR, for Personal Record). "No one goes out thinking of winning," Garcia, a celebrity chef and longtime endurance runner, tells the group. "They go out thinking about not losing."

And even that modest goal can be unattainable. Goodman, a three-time TBA whose athletic resume includes playing basketball for Coach Krzyzewski at Duke University, has come in dead last at a few GYAS events—a PW for which he feels no shame. "It’s amazing how many people who win stick around to cheer for the people coming in last," he notes.

Just like the sport of running, A World Gone Mad for Marathons offers insight on how to tolerate uncertainty and to be open to the twists and turns life throws our way. The profiles illustrate how a select few make sense of adversity by tapping into their pain meters and going back for more. "There’s something under there," Kimball tells the crowd. "If you dig far enough, you can shift to being a happier person. That’s what running and enduring this stuff together teaches us."

Like a proud coach, Sam regards his assembled guests of honor. "You all have a story that resonated with the theme of the book," he explains. "You all have your 'why I do this.'" He’s talking about adversity—each runner has faced and overcome personal challenges and setbacks. From terminal illness, depression, gender barriers, aging athleticism, and traumatic injury, all five athletes at the table—and all ten in the book—are survivors who have found greater strength by directing their challenges toward purpose.

"There’s nothing more empowering than the feeling of being so close to your own mortality to make you feel alive," Whitaker tells the group. "These races are such a metaphor for the challenges we all face. Is a race the hardest thing that’s going to happen to us in our lives? Probably not, there’s certainly more ahead for all of us. And just like in the Madison Marathon, you come around the corner, see the next hill, and move forward."