Make a Statement

Gaining access to school-trust lands.

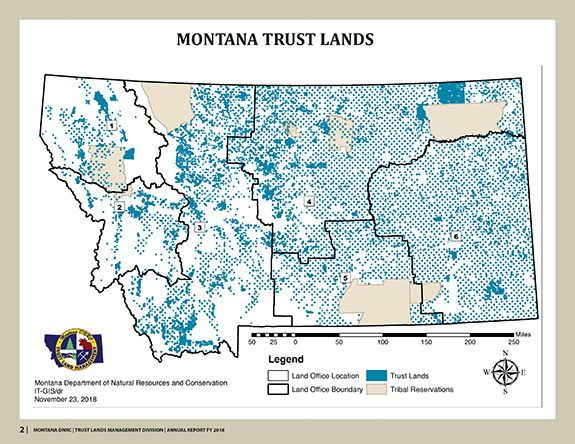

While the debate over public-lands access has hit the mainstream, the issue has been brewing for decades. Even back in the 1950s, recreationists argued that Montana’s 5.2-million acres of school-trust lands belonged to the public and should be open to recreational use. In 1967, during the 40th Legislature, Senate Joint Resolution No. 19 directed the Committee to Study the Diversified Uses of State Lands “to develop means to provide for the overall use of the State-owned lands for both public recreation and agricultural pursuits.” The Committee was responsible for drafting the multiple-use policy language written into statute in 1969, and while multiple-use was written into statute, it was not actually implemented. In the State’s Recreational Use Report, it wrote that the State’s allowing lessees to manage school-trust land, “has resulted in a proprietary feeling among many of the lessees over ‘their’ state land.” Some farm and ranch operations were 70%, 80%, and 100% school-trust lands.

In 1971, the Department of State Lands (DSL) began a survey, the Recreational Inventory Program. The survey was to identify recreational opportunities, locations of uses, and general recreation potential. The survey wasn’t completed and they didn’t finish the report until 1982, 11 years later, and still recreational access was not forthcoming.

In October 1978, three Montana hunters, Jack Atcheson Sr., Jack Jones (BLM), and Steve Bayless (FWP) were sharptail hunting in Malta, north of the Milk River, on BLM land. They tried to hunt the connected “blue-colored” Montana state school-trust lands section on the map, only to have Mr. White (the grazing lessee), drive up in his pickup truck threatening them with, “You guys get the hell off my land now!” This incident sparked Atcheson’s quest to find out about these “blue” state lands, later joined by Tony Schoonen and Jones when he retired from the BLM. The more these conservation-minded hunters and anglers learned, the more they believed that Montana state lands entitled them to public access, especially since their taxpayer dollars paid for State Lands administration—the State Land Board administration was funded by $2 million of Montana general taxpayer dollars annually. They spread their newfound knowledge throughout the hunting and angling community, eventually leading to the recreation access we enjoy today. Our Montana Constitution, Article X Education and Public Lands, Section 11 Public Land Trust disposition now reads, “All lands of the state that have been or may be granted by congress... shall be public lands of the state. They shall be held in trust for the people...”

In 1980, Atcheson, Jones, Schoonen and others created the Montana Coalition for Appropriate Management of State Lands and the Montana Coalition for Stream Access. They decided to first pursue stream access, which became law in 1985. In February 1988, the Coalition filed a lawsuit against the DSL and the State Land Board, at the district court in Helena, for failure to comply with the Enabling Act, the State Constitution, state laws and policies, and the Montana Multiple Use Act. Lessees pushed against public access; the Coalition pushed back by demanding that the DSL prepare an environmental-impact statement on its grazing lease program. The Coalition alleged that if the state must charge for recreational access, it must develop a system of availability of state lands and compensation secured, as well as enforcing that the minimum rates for grazing land be increased.

This lawsuit expanded the conversation about and scrutiny of state-land management. Educated sportsmen began providing documentation that further evidenced the state’s mismanagement of school-trust lands, especially funding schools and the contradicting lack of access. Major points brought up were: other western states had public access without cost; our state taxpayers funded the General Fund, which paid about 50% of the DSL’s budget; inappropriate grazing-lease prices; leased areas were posted No Hunting while lessees and their friends hunted; leases were illegally subleased; 70% of leases were by nonresidents; and the fact that exclusive use of state public lands posted against trespassing should be subject to taxation under MCA 15-24-1203 “privilege-use” tax.

The Coalition lawsuit stated, “It is the position of the plaintiff that judicial action is necessary to compel the state defendants to administer the public lands of the State of Montana according to the requirements of the Montana Constitution and the Multiple Use Act, MCA 77-1-203. As demonstrated below, the DSL and the Board have long stifled public efforts to get those departments to manage the state public lands on a multiple-use basis and to allow public recreational use. For years, the agencies have promised one thing (that they were developing a meaningful recreational inventory and working on a program to accomplish public access) and done another. They have bureaucratically stifled any progress on public access.”

Representative Dave Brown introduced two bills in 1991 to address state-lands recreational access: HB 401 and HB 778, eventually merging portions of HB 401 with 778. On April 25, Governor Stevens signed HB 778 into law, making the effective date March 1, 1992.

In 1993 recreationists continued the fight on school-trust lands. A number of hunting/angling groups orchestrated petitions for four Administrative Rules changes: 1) expand the General Recreation definition to include camping, hiking, berry & mushroom picking, horseback riding, photography, etc.; 2) recognize roads and vehicle use; 3) do not restrict state parcels involved with FWP Block Management agreements differently than other public lands; and 4) eliminate the posting of state lands with orange paint, which is reserved for private property.

In March and July 1994, the Administrative Rules adopted the revised rules. Instead of listing all the different types of General Recreation in 36.25.145 (then 26.3.180), the new rules are generally inclusive and simply list what you can’t do on state lands. The other rules had minor changes.

Disappointingly, the school-trust lands battle does not share the victories that Stream Access has enjoyed. There are still implementation issues with recreational access on school-trust lands, as well as the original conflicts brought up by the Coalition. A Recreational Inventory of state lands has not been produced and the person in charge of recreation is the ag/grazing management administrator. Far too many public recreationists are unaware of recreational opportunities on state lands, how to hold DSL accountable, or stand firm for those hard-fought rights.

As recreationists, it looks like we have our state-lands management work cut out for us. We owe a debt to those who began this decades-long battle and have continued the process, though many were unaware. Perhaps, this management and access history will assist the public in overseeing and demanding the lawfully required administration of these school-trust lands, as well as utilizing and defending our recreational opportunities on the 5.2-million acres, which our Constitution states, “...shall be public lands of the state. They shall be held in trust for the people...” That means all the people of Montana!

This article originally appeared on the PLWA website.