Eastbound & Down

Hunting Montana's eastern prairies.

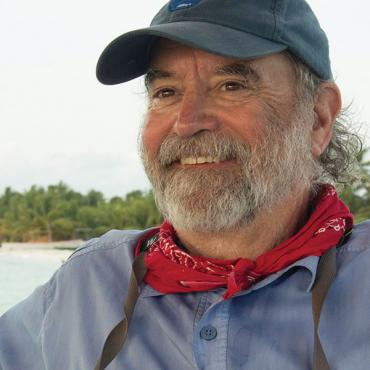

I’d spent an hour sitting motionless in the sage while I observed the pronghorn herd. Running through September, Montana’s archery antelope season includes the heart of the annual rut, and the non-stop interaction between bucks and does provides a fascinating spectacle. The terrain was open prairie, which made an undetected approach for longbow range a challenge.

Then, one of the young bucks that had been expectantly circling the herd made his move, cutting a doe out of the dominant buck’s harem. The herd buck took off in furious pursuit, and I enjoyed the show—our continent’s fastest mammal chewing up miles of sagebrush at breakneck speed. Watching the three of them disappear over a distant rise, I calculated the herd buck’s most likely route of return to his does after the chase and slowly began my way toward an ambush.

The mountainous western third of Montana attracts the tourists, makes the coffee-table spreads, and dominates the state’s population centers. But all across the world, savannah habitat supports the richest wildlife habitat, greatest biodiversity, and highest carrying capacity. Our slice of the state offers ready access to the best of both worlds, and hunters should not ignore the breaks and prairies during the fall.

Widely renowned for their speed and keen eyesight, pronghorn antelope are our iconic prairie big-game animal. (They aren’t true antelope at all, but the biologists can worry about that.) The state requires drawing permits allotted by hunting district in order to pursue them, but they aren’t hard to obtain, especially in Regions 6 and 7; and it’s even easier for archery tags. No matter what one’s choice of weapon, pronghorns will test a hunter’s stalking skills to the absolute limit.

While popular imagination usually associates elk with timbered, mountainous terrain, the journals of Lewis & Clark tell a different story. Two hundred years ago, before unregulated subsistence hunting eliminated most of them, eastern Montana was loaded with elk. Their successful reintroduction is one of our great wildlife success stories, and eastern Montana now offers some of the country’s best elk hunting, especially in the Missouri River Breaks (where permits are also required to hunt).

Eastern Montana lowlands also offer excellent deer hunting, with muleys widely distributed across the open prairie and foothills of the area’s isolated island mountain ranges, as well as whitetails concentrated in river bottoms. The upland bird hunting is the most productive in the state, offering abundant sharptails, Hungarian partridge, and pheasants.

Whatever the quarry, hunting this terrain differs from mountain hunting in distinct ways. Here follows some advice for newcomers.

While a lot of this country appears flat at first glance, much of it is surprisingly rugged, especially in the breaks along the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, and their tributaries. Physical conditioning can be just as important as it is in the hills.

Potable water can be scarce, and hunters should be sure to carry adequate supplies both on their persons and in their vehicles. When it does rain, visitors will face another problem as many backroads turn into impassable gumbo that neither chains nor four-wheel-drive can overcome. When rain threatens, head for pavement.

Because this is such open country, good optics are especially important for big-game hunters. It’s easier to find game with your eyes than with your legs, so don’t skimp on the quality of binoculars and spotting scopes.

|

|

Prior to snow and freezing weather, this is serious snake country. While the chance of a venomous bite is low, I always watch my step. If you’re hunting with bird dogs, consider putting them through a snake-avoidance clinic, which I think is the best way to avoid losing a dog to snakebite.

Prairie terrain is subject to sudden, extreme weather fluctuations. I’ve hunted in temperatures ranging from over 100 to well below zero, and strong winds are always possible. After one frigid late-season goose hunt, I had to walk backward into the wind for a mile so my eyelids wouldn’t freeze shut. Dress in layers and pack clothing suitable for a variety of weather.

While lots of this habitat lies in the public domain, some of it doesn’t. GPS technology such as OnX can be an invaluable aid to keeping you on the right side of the fence.

Thorns from prickly pear and other cactus species can be a problem. Knee and elbow pads are helpful on belly-crawling stalks, and footwear should have thick, tough soles to ward off spines.

At the beginning of my attempt upon that pronghorn buck, I estimated the odds against me as one in a million. But as Jim Carrey said in Dumb and Dumber, I had a chance. In fact, the buck ambled back to his herd along the exact route I predicted, allowing me to send an arrow through his chest from 15 yards.

That was just one of countless challenges the prairie has offered me over the years. Sometimes, I can even rise to meet them.

The Road Home

The culmination of a good prairie hunt is not the kill—oftentimes, that’s the easy part. Getting the animal home, in good condition, is the real end-game, and often where the greater challenge lies. From field to freezer, a lot can go wrong. Here’s how to do it right.

In the Field

A quick, clean kill is essential; any kind of prolonged struggle can taint the meat. Gut the animal quickly, and get the carcass back to the truck—whole, if possible. Protect any exposed flesh with cheesecloth or game bags. The most important thing is to allow the meat to breathe—open up the ribcage with a stick, and lay the animal on its back with legs splayed open. Or hang it from a tree limb in a similar posture.

If the air is above 50 degrees, get home as soon as possible. Below that, or if it gets cold at night, hang the animal in the shade and feel the meat every so often. As long as it remains cold to the touch throughout the day, you should be fine. But always err on the side of caution, especially with antelope. If you’re nervous about spoilage, get the hide off, quarter the animal, and put it in a cooler.

On the Road

Before a long drive on a warm day, it may be tempting to stuff a carcass full of bagged ice and make a break for it. This is a mistake. The ice generally cools the surface only, and may actually hinder the interior from cooling. Airflow is more important—if you’ve got a topper on your truck, open up the windows.

The safest bet is to bring a cooler along—a big one, or several smaller ones. Backstraps, loins, and trim (rib and neck meat, etc.) should go in first, as they’re more vulnerable. Next come the quarters, which can be de-boned if space is an issue. Block ice is best, with a layer of cardboard between the ice and the meat to prevent freezer burn.

|

|

Coolers make a great back-up plan, too. Two years ago, my brother and I were racing the clock, trying to get home with two mule deer on a rapidly-warming October day. Outside of Billings, my truck broke down. As cars zipped by on I-90, we quartered the deer on the tailgate and put them in the cooler. Then we cracked a beer and waited patiently for the tow truck.

If you’re from out of state, another option is to drop your animal at a local processor. You can pay for expedited processing, or have them ship your meat home for you. It’s spendy, but often safer than driving it home yourself, which may include dry ice, several quarts of coffee, and a radar detector. —Mike England