Rookie Mistake

I had a cow and a calf in my crosshairs. The calf looked back at me with a sad look, as if to say, “Please don’t shoot my mom.” I lowered my rifle. Then the alarm clock woke me.

It was closing day of my first hunting season, during my first year in Montana. Being from Philadelphia, I was clueless. Where I come from, we bludgeon our targets—usually Dallas Cowboys—with D batteries (Eagles fans often show their spirit by chucking Energizers at the opposing team). Fortunately, a friend of a friend, who had been hunting for 30 years, offered to teach me the ropes.

He was very nice but seemed a little like Cliff Clavin, the loquacious mailman who spewed useless trivia on the TV show Cheers. He talked a lot about hunting, but I wasn’t sure how much he really knew. I reminded myself, however, that he had several giant antlers on his wall and I was green.

On a dark drive to Gardiner, I asked Cliff about the dream. “What’s the proper etiquette in that situation? Will other hunters shun me if I shoot the cow or the calf?”

He replied, “Shoot them both. Both are legal where we’re going. Some would argue in favor of shooting the cow because you’d get more meat. Others would say the calf because it’s more tender. Either way, you’re good. Spike bulls and mulies of either sex are the only things you can’t shoot today.”

The road into the mountains past Gardiner looked like the closing scene from Field of Dreams: miles of headlights weaving through the darkness. Thirty minutes before sunup, so many shots rang out that it sounded like machine-gun fire. We, however, saw nothing. Driving up the road, I noticed nine cow elk on top of a bluff that no one else had spotted. Cliff said they were ours. We parked a couple bluffs down. He read the regs again. “Yep. No mulies and no spikes. Let’s get ‘em.”

We made our way through the knee-deep snow. Shots rang out. “They’re being pushed,” Cliff proclaimed. He began to run, and I followed. We reached them as they ran through a gully. “Shoot the ones in front,” Cliff directed.

Taking aim amid desperate gasps for oxygen, I had a new respect for biathletes. The two in front were a cow and a calf. The calf looked at me, and I couldn’t do it. I lowered my rifle as Cliff fired. Behind them was a giant cow, the biggest of the bunch, all by herself. I took careful aim and fired. She flinched and then ran from sight.

We found two blood trails in the snow. Neither of us managed a clean shot. We followed the red trickles through a herd of seven wild buffalo, which for a Philly boy was the coolest thing ever. We caught up to the smaller elk. Cliff shot and missed. She was about to drop out of sight, but I was able to put her down.

Cliff said to leave her. We needed to catch the big one. After a mile, we weren’t gaining any ground and shots echoed in her direction. Cliff instructed me to go back and deal with the other one while he continued. Me “dealing with the other one” meant waiting for him, as I did not know what to do next. He eventually returned empty-handed. He said some other hunters were closing in on her.

We gutted the elk and went back to the truck to get a rope. I was as giddy as a schoolgirl. I killed my first animal, filled my freezer, and hiked through wild buffalo—this was the greatest day ever. As we moved the truck closer, we saw the game warden who was a friend of Cliff’s. He stopped to say hello. The warden asked if we had any luck.

Still euphoric, I exclaimed, “I shot my first elk!”

He said, “Congratulations. How many points?”

I replied, “No points. It was a cow.”

“Do you have the special tag?” he responded with a ball-busting tone. “You can’t shoot cows here without the special tag.”

I confidently called his bluff. “Nothing special about my tag, but I shot her dead.”

A somber expression overcame him and I knew he wasn’t trying to make me sweat. “You really shot a cow?”

I nodded, feeling gut-shot myself. As it turned out, Cliff had read the regulations wrong. My day just took a nosedive.

The warden leaned into the car and in a discreet tone said, “Here’s my cell phone number. Get her in your truck, call me when you get back to town, and we’ll take care of this.”

I didn’t know what he meant by that. My Philly interpretation was that if I gave him some choice cuts, I was going to get to keep the rest. Cliff said something similar as we drove away. Others have said that was never going to happen.

Cliff said rather than attempting to quarter her, we would get the warden to use his winch to lift her in the truck whole. We drove back to where we left him, but he was gone. There was, however, a sheriff. Cliff pulled up and asked him if he saw the warden.

He said, “Yes. He was heading back to Bozeman. Why?”

I could feel it coming, despite my internal screaming of Don’t say it!

“We illegally shot an elk and he was supposed to help us take care of it,” replied Cliff.

I can’t believe he said it, I thought to myself with disgust.

The sheriff smiled and said, “Really?”

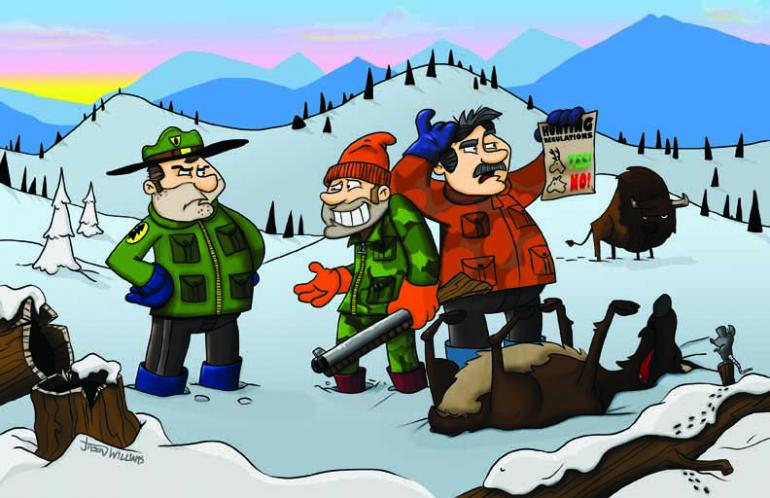

He called the warden on the walkie and quoted Cliff’s call for help. When the warden returned, he looked at us like we were mentally handicapped. He confiscated the animal, which was donated to the food bank, and fined me for poaching. As he handed me the fine he said, “I can’t enforce this, but I highly recommend you two split this.”

Cliff did pay half. And I learned a valuable lesson. No matter how experienced or literate your hunting guide appears to be, always read the regulations yourself.