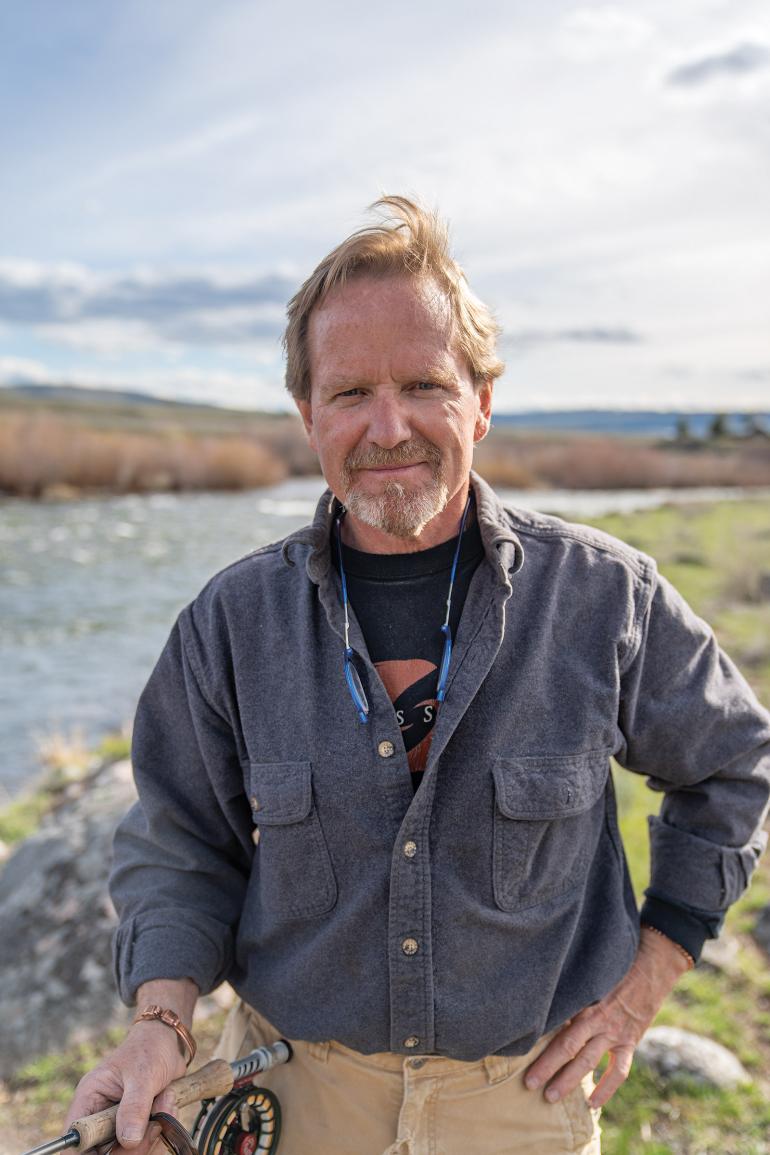

Tied to the River

Inside the Sex Dungeon with fly fishing’s streamer stud.

Kelly was shorter than the grass, so he couldn’t see the stream his dad was fishing. But he could hear it. And he could see his dad’s rod tip floating in the sky and smell the smoke from his cigarette. Then the rod tip quivered and plunged downwards, and after a brief fight, his dad pulled up a glistening brown trout, about 16 inches from tip to tail.

That’s the first thing Kelly Galloup remembers. Before he became a fishing guide, started his own fly shop, and designed some of the most iconic streamers in the sport (and literally wrote the book on them), Kelly grew up near Traverse City, Michigan, fishing creeks with his dad for trout like that first big brown.

“I remember taking that fish to my grandma’s house, chest pumped out like I’d just won a fucking medal,” he recalls. “I didn’t do a thing.”

But it didn’t take Kelly long to start catching fish of his own. The Galloups lived in Acme, and before Kelly could drive, his mom would drop him off at nearby streams or rivers like the Boardman or the Platte to fish all day and pick him up at dinnertime. When he turned 16, his mom bought him an old jalopy, and although he confesses to having two addictions at the time—fishing and girls—his first idea wasn’t to go chasing chicks from his high school.

“She handed me those keys and the first thought I had was, I can fish anywhere I want.”

He drove to a nearby river and went fishing by himself, with no time limit, and for him, it was the coolest thing in the world. That was the same year he started guiding. His dad was the first fishing guide on the Pere Marquette River (commonly known as the PM) back in 1940, and although Kelly didn’t fish with him much, his dad did give him one piece of advice before Kelly took out his first client: “Make him a good lunch.”

When Kelly turned 16, his mom bought him an old jalopy, and although he confesses to having two addictions at the time—fishing and girls—his first idea wasn’t to go chasing chicks from his high school.

Kelly ran about ten trips that first year, all with the same guy and his kids, and guiding at the time was very informal. Most guides fished out the back of the driftboat as they rowed their clients downstream, and 30 trips a year was considered a heavy workload. In the ’70s, there wasn’t much competition, and Kelly could float streams like the Boardman, Au Sable, and PM and never see another boat on the river.

By the ’90s, the fly-fishing industry would be booming, the salmon fishery alone turning into a billion-dollar business almost overnight, and Kelly’s beloved rivers would be crawling with fishermen year-round, bringing him plenty of business, but also making him think about leaving his home behind in search of open waters.

For decades, however, he enjoyed long, uninterrupted days of peaceful fishing, logging thousands of hours on the river and accumulating the experience he would later use to write Modern Streamers for Trophy Trout, the book that made him a household name to avid anglers.

But on his way to success and notoriety, Kelly’s life took a detour.

In 1980, Kelly was in Houston, Texas, thousands of miles from Michigan’s fabled trout streams. He was taking steroids, training every day with professional bodybuilders, and he weighed 240 pounds—70 pounds heavier than when he graduated high school just a few years prior. Kelly’s cousin got him into bodybuilding as a 17-year-old, and he quickly became consumed by it, giving up sports and his social life to train.

That’s how he found himself in Houston as a 21-year-old with 19-inch arms, and after four years of bodybuilding, its narcissism, neuroticism, and extreme physical discipline were taking a toll on him. The only thing that kept him sane was tying flies.

“I tied a lot down there,” Kelly says. “That’s the only way I grounded myself to not be suicidal.”

Flies and fly fishing gave Kelly something to pour his energy into.

Fly-tying had always been a sort of salvation for Kelly. He admits to being a spoiled, rotten kid who was always getting in trouble (he tells a story of his high-school English teacher running across the street after his first book was published and telling him, “No, you’re not supposed to write a book. Your brother’s supposed to write a book. You’re supposed to be in jail!”). But flies and fly fishing gave him something else to pour his energy into. His mom, who was a skilled woodworker, actually built him a station to tie flies when he was five. “I think that fucking saved me,” he remembers.

While he was in Houston, Kelly didn’t see a trout for five months—the longest stretch in his life he’d ever gone without fishing—and he began imagining a new life for himself when he got back home. “I swore to myself I’d never do that again,” he says.

Kelly returned to Michigan in the springtime. He crashed at his parents’ house (he didn’t have an apartment yet) and the next morning he got up at 3am, drove to the Platte River, and sat there for three hours in the dark, listening to the familiar rush of water. He was back where he belonged.

Within a year he’d started the Troutsman, a fly shop and guide service in Traverse City. When he told his boss at Shell Oil, where he worked as a lease operator, that he was quitting to start a fly shop, his boss asked what he was going to do with them.

“I’m like, ‘With what?’ The flies. He thought I was going to raise flies!”

Though there were plenty of bait shops in Michigan, fly shops were all but unheard of. But that wouldn’t last long. Doug Swisher and Carl Richards’ books Selective Trout and Strategies for Selective Trout helped draw attention to fly fishing, and when the fly-fishing movie A River Runs Through It was released in 1992, the floodgates opened. People descended upon Michigan rivers from Chicago, Detroit, and the surrounding areas to fish, and when they did, Kelly was ready for them. He hired more guides, tied more patterns, and established himself as one of the premiere outfitters in northern Michigan, servicing the streams he’d been fishing since he was a teen. But success came with sacrifice, as the increasing number of anglers on the river started getting in each other’s way.

Although Kelly enjoys the attention, that’s not the kind of recognition he values most—if he’s remembered at all, Kelly would like it to be as a teacher.

Kelly admits he was part of the problem. In 1999, he published Modern Streamers for Trophy Trout, a book he wrote with friend and fellow angler Bob Linsenman that helped popularize streamer fishing and threw fuel on the fire of the fly-fishing craze. Streamer fishing had been around for a while—it first found a foothold in Maine in the 1920s with the invention of the Mickey Finn and the Gray Ghost—but had yet to catch on nationwide, and very few people were casting streamers elsewhere. With Modern Streamers, Kelly quickly developed a reputation, and more and more people started using the big, subsurface patterns to target monster trout.

Fly fishing’s sudden popularity was a boon for business—Kelly’s shop was running about a thousand trips a year by 2000—but he couldn’t wait to get off the river.

“It was a double-edged sword,” Kelly said. “I rode the wave. But it was one of the big impetuses for me to leave, too.”

Kelly had been on several fishing trips to Montana, and as Michigan trout streams filled up with anglers, he began imagining a new life for himself under the big sky, fishing bigger water. So in 2001, he headed west. By that time Kelly was married with three kids, so it was the five of them that packed up and drove cross-country to land on the banks of the Madison River.

His wife, Penny, grew up in a rural area, but their new home was a different kind of remote—42 miles away from the nearest town: Ennis, population 864. The first two years, all five of them shared 600 square feet of space, half of which was devoted to the fly shop, but Kelly promised his wife a big house by their third year, and once it was built, they bought horses for the kids to ride. He and his wife eventually divorced when the kids were in their teens; Penny moved to Bozeman and the kids grew up and moved on. But Kelly was there to stay.

23 years and 11 remodels later, Galloup’s Slide Inn is now 5,600 square feet instead of 600, and in 2023, Kelly opened a second location in Ennis. Walk into either of his shops today and you’ll find a panoply of different flies and streamers, many of his own design, with names like the Sex Dungeon, the Stacked Blonde, the Butt Monkey, and the Belly Bumper (Kelly Galloup flies are legendary for their lewd nomenclature, which has led some to speculate that he was a porn star in the ’70s—Kelly will neither confirm nor deny these claims).

A visitor to the Slide Inn will be greeted by one of his guides, or by Kelly himself, and can chat about fly patterns, seasonal trout feeding habits, or the insights in Kelly’s new book Modern Streamers II, the 2020 update to his classic. The Slide also runs hundreds of guided fishing trips on the Madison each year, and many of Kelly’s guides are from Michigan, having followed in his footsteps from east to west.

Each of his first 10 years in Montana, Kelly spent over 200 days drifting rivers—no small feat given the region’s long, bitterly cold winters. But he’s since taken a step back from guiding and his objectives as a fisherman have changed. “Catching fish means very little to me,” Kelly says. He’d rather fish new water or float with his guides, watching how they cast and retrieve to determine how tweaking a streamer might help them find trout.

Kelly also films videos for the Slide Inn YouTube channel where he gives advice to anglers while he’s fishing, anything from simple tactics like carrying a rag to dry your hands to the less conventional edict to “get drunk, get naked, get in the neighbors’ pool and throw flies around.” He’s writing another book for former athletes to help with the transition from sports back to normal life, and occasionally flies across the country to give seminars on fly-fishing’s more technical aspects—and almost always gets stopped in the airport by fishing acolytes that either recognize him from his book or his YouTube channel.

Although he enjoys the attention, that’s not the kind of recognition he values most—if he’s remembered at all, Kelly would like it to be as a teacher.

“I didn’t ever really think about being famous, and I never thought I’d write a book—didn’t think I could figure out which end of the pencil to use. But I always liked the accolade of ‘Thank you.’ It’s how many people come back and say, ‘I did what you said, and it made my life easier, it made my fishing better.’ I still live off that every day.”

Fly fishing in Montana has gained popularity over the past few decades, but despite more anglers crowding boat launches, clogging up fishing-access sites, and occasionally trespassing in Kelly’s backyard to take a leak on his lawn, he’s not itching to run for open waters.

As long as people keep walking in through his door at the Slide Inn, Kelly will keep sending them out with a new fly, a new technique, or a new perspective on fishing.

He tells a story of an 80-year-old who came into the Slide and said, “I’m old enough to tell you the fucking truth: I wish not one of you motherfuckers was ever here. I’ve been fishing here for 60 years, and I think every one of you is a pain in my ass.”

Kelly just thanked the old-timer and chuckled. To Kelly, everyone on the river is trying to enjoy the same thing, and no one has a special right to do so. He sums it up this way: “It’s just too many rats in the cage.”

His advice for those who don’t like competing with other fishermen for trout? Get better. “Learn new techniques, go to new water, go earlier, go later; do anything but bitch about it.” He expects this attitude from his guides, all of whom fish four, five, even six times a week after work, sometimes floating the Madison at midnight to find undisturbed water.

Kelly’s fond of quoting an interview he once saw with the oldest man in the world: “Embrace change, even if you hate it. Otherwise you’ll end up one of those grumpy old bastards.”

Kelly guffaws as he says this. He’s not one of those grumpy old bastards yet. After a life of teaching people how to fish, he’s not going to begrudge others who discover their own love for the sport. As long as people keep walking in through his door at the Slide Inn, Kelly will keep sending them out with a new fly, a new technique, or a new perspective on fishing, the activity that’s defined his life for as long as he can remember.