Mighty Whitey

In defense of trashfish.

As marked by the publication of Isaak Walton’s Compleat Angler in 1653, people have been getting fishing line tangled in branches for at least three and a half centuries. Catch-and-release angling is a more recent development, not being popularized until the mid-twentieth century. Perhaps due to this recency, it continues to be rare in many parts of the country. And yet, catch-and-release fly-anglers, while definitely more prone to snagging riparian vegetation, often carry a less-than-positive attitude towards their bait- and lure-casting brethren. My home state of Montana provides the perfect microcosm where catch-and-release and harvest-fishing collide.

Despite vast eco- and geological differences, fishing is incredibly prevalent in both eastern and western Montana. However, unlike here, eastern Montana anglers rarely practice catch-and-release for all fishes. Now, some may argue that the reason catch-and-release is so common in coldwater trout country is that trout do not taste as good as the catfish, sauger, or bass of the muddy plains rivers. They would probably be at least partially correct. Regardless, there is a view among some catch-and-release anglers that folks who harvest fish are “low-class” or even a bit “backwards.” Naturally, this attitude angers the non-catch-and-release crowd and the two factions are often at odds. As an aspiring five-tool angler (dry fly, nymph, streamer, bait, and lure fishing) and resident of both western and eastern Montana, I have the dubious distinction of being annoyed with both groups. While I, of course, get along with anglers of both factions, my annoyance is with a failing I see present among many fly and bait anglers alike. It can all be summed up by one word, “trashfish.”

My primary problem with the word “trashfish” is that it exists at all. Calling a fish trash simply because it has no perceived utility to the angler is akin to calling wildflowers trash because you do not like eating flowers. Yet, you never hear the term “trashflower.” Let me explain.

We all like to catch big trout, catfish, or other gamefish and all need certain conditions to live. Unknown to many, Montana Fish, Wildlife, & Parks does not stock fish in rivers unless that species is severely at risk (pallid sturgeon, Arctic grayling, etc.). Instead, they allow nature to do what it has always done and rely on it to produce wild fish. In the end, this “management” action actually produces more fish (go figure). However, nature can only produce fish if all the correct pieces are in place. For a fish to grow, a river must be free of pollution, have the correct type of spawning grounds, not be too hot or cold, have plenty of water, be connected to its tributaries, flow freely, and provide enough food. If any one of those components is absent, the fish population declines. To provide enough food, there must be plenty of “trashfish” for gamefishes to consume. On the river, I have often observed anglers killing “trashfish” and throwing them back in the water, thinking that there will now be one less mouth for gamefishes to compete against. However, this is contrary to what is best for gamefishes. As we know, most fish produce tons of eggs every year, only a few of which grow to adulthood. While sad, this thinning is a natural part of a fish’s life and many of those eggs and young go on to feed larger fish. So, when a “trashfish” is removed from the river, gamefishes are actually being deprived of a very important food source that includes all the eggs and young that dead fish will no longer produce. It’s like removing the wildflowers that seem useless, but actually provide important forage for elk, deer, bees, and other animals we rely on.

Nature is an incredibly complex web of different organisms, all of which impact each other in a myriad of ways, directly or indirectly. For one type of organism to persist, a great many others must as well. The web of life is so intricate that removal of one species will affect countless, unknowable others. With that in mind, next time you catch that whitefish, goldeye, or sucker, think twice before knocking it on the head. Remember, there is no such thing as a “trashfish.”

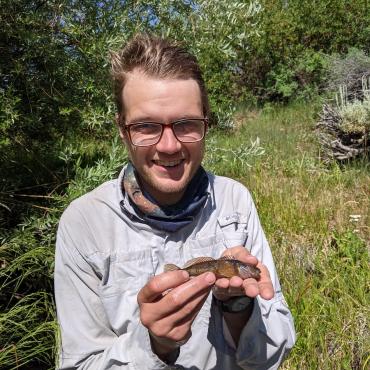

Niall Clancy is a fisheries scientist at Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks.

Trout is Out

A gleaming trout may be the holy image of fishing in Montana, but there are a lot more species swimming around our pristine waters. Consider these other fish for a fun catch or as a feature on your dinner plate this summer.

Carp

This non-native species is common in lakes and larger rivers. Considered a nuisance, they make great targets when you’re trying to hone your bow-fishing skills. Carp prefer warm shallows and weedy areas. Carp get a bad rep for a fishy flavor, especially when caught in turbid waters; but it is often enjoyed smoked or pickled. Spin-fish with live bait or for a real challenge—and a strong fight—try to entice them with a nymph, streamer, or crayfish pattern.

Suckers

Several native species are found all over Montana, from river drainages to reservoirs to lakes. The most abundant, the longnose sucker, can be found in clear, cold streams. A healthy sucker population is a good indicator of a healthy river, as they are sensitive to pollutants. Suckers are a strong and energetic species, ensuring a fun catch. Worms or other live bait, bounced along the bottom, is the best bet here, though a large nymph may induce a strike, too.

Perch

Perch are an abundant non-native species common throughout the state. They can make for a successful day on the water, and a great way to get kids excited about fishing. They are aggressive eaters, often caught with just a bit of worm, and sometimes even a plain hook. Found in lakes and reservoirs, perch are also a popular ice-fishing target. They’ll fall for a variety of baits, spinners, and flies alike, so pick your passion.

Walleye

Walleye tend to live most of their lives in deep lakes, but will migrate to spawn in feeder streams. When lake-fishing from a boat, a fishfinder is a handy tool to seek them out. Cast or troll spinners or spoons; live bait is extremely effective, too. As any Midwestern angler can confirm, your palate will thank you after sinking your teeth into a beer-battered walleye fillet.

Pike

Pike are the scary prehistoric-looking beasts lurking in lakes and big-river backwaters. These water monsters are voracious predators and wield a toothy grin. Spin-casting works best, but they can make for an exciting challenge on a fly rod, too. Either way, a wire leader is essential to keep their gator-like fangs from shredding your line.

—Dawn Brintnall