Float It In

Canoe camping made easy.

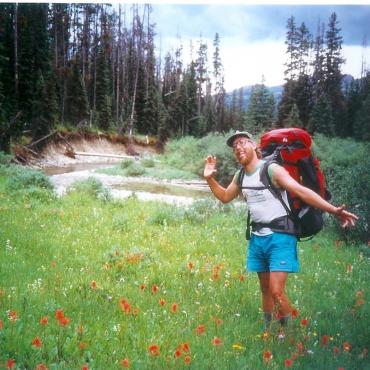

As middle age shrinks in the rearview mirror, one becomes somewhat less enamored with dragging luggage over rugged Rocky Mountain ridges. If you’re over backpacking and still want to camp, you can always join the other over-the-hill hordes in Winnebago Land. But why not let water and gravity carry your swag instead?

For those of you familiar with the decadent world of raft trips, you know the amount of gear that can be transported down a river. Luxurious for sure, but loading and unloading the boats—not to mention trying to get through all those cases of Schmidt—can be a real chore. Try canoe camping, a sort of “rafting lite.” You’ve got less gear to wrangle, but it’s still a far cry from the labor of backpacking.

My wife and I got a canoe as a wedding present from family and friends. For the past 18 years, that craft has allowed us to paddle and weave down many a fine river and across sparkling lakes. Many trips have been multi-day excursions, including 150 miles through the Missouri Breaks.

Thanks to the buoyancy and easy handling of a canoe, you can pack all manner of comforts along. Cooler of fresh food and beer? Check. Folding camp chairs? Essential. Large, family-style tent? Why not? If it fits in the boat, and your load isn’t too top heavy, you can bring it. Hell, throw in the croquet set and Dutch oven. Food is stored in five-gallon buckets with lids, which double as seats in camp.

Dry bags are essential for clothing and sleeping gear. Get large dry bags with pack straps to make carrying easier. If you’re doing any portaging this will be a huge help. For canoe camping, we use a tent big enough to stand up in and walk in and out of. At my age, you get tired of crawling through a dog-sized door, and contorting yourself trying to escape for midnight bathroom breaks. If it’s buggy or stormy, we set the chairs up in the tent and sit inside in comfort, reading or visiting without swatting and cursing. We never bring any food into the tent though, and only water to drink—in bear country, hang ALL of your food and cooking gear, (including the cooler) away from camp. In Glacier Park we discovered that mice will climb ropes and cords and chew through food bags, but coolers keep them out. Along some rivers it may not be as crucial to hang your food, but remember that skunks, raccoons, marmots, and other varmints are out there too.

I also recommend a large tarp rigged as a kitchen shelter, which extends your living area in bad weather. The top of your cooler makes a good table, and for cooking, a two-burner Coleman-style stove is the ticket. A five-gallon water jug means you can bring enough drinking water for a few days without having to filter it.

Be mindful of where you camp—no one wants to wake up with a rancher’s shotgun in his or her face. Public access is limited in Montana to below the high-water line on rivers. There’s public land along some rivers, such as the islands on the lower Yellowstone, so read your maps with care. Minimize your impact by not camping too close to the river, and wash your dishes well away from the water. Some rivers and reservoirs can rise fairly quickly—another good reason to camp up the hill.

Beware of wind—I’ve rescued several tents that were blowing away like misshapen hot-air balloons. Canoes can also launch themselves in high winds, so empty your boat and tie it to a tree well above high water.

Use your imagination to plan canoe trips; this form of backcountry living provides rare freedom from limitation. With waterways and lakes gracing so much of Montana, your options are endless—and your camps can be downright luxurious.

Phil Knight is a guide/naturalist who moved to Bozeman in 1985, fleeing a life of indolence and sloth back east.