Across the Ice

Winter camping by bike.

The doldrums of 2011-12’s El Niño hit in February. Little snow had fallen since Christmas and a persistent high-pressure system reduced the skiing to hard and scratchy snow at the resorts, or a backcountry plagued with a thin and hollow snowpack. The Nordic tracks were recycled and crystalized corduroy.

While snowsports enthusiasts were singing the blues early, it was shaping up to be a banner season for ice. The ice-climbing scene was going off up Hyalite Canyon and the region’s lakes and ponds formed a thick and dependable layer for those who prefer horizontally glazed recreation.

Canyon Ferry, the first dammed reservoir on the Missouri—some 35,000 acres with 76 miles of shoreline—was all but completely frozen by mid-December, and by February, 14-inch-thick ice stretched for miles. Motivated ice fishermen chased perch through the floors of their ramshackle ice-huts, and most weekends there were parties of skaters complete with bonfires and cocoa-filled thermoses just off shore from the Silos boat ramp. On windy days, low-slung, sail-driven iceboats ripped high-speed tacks across the lake.

Restless from inactivity, we went in search of our own alternative to the usual winter-weekend escape. Cold-weather commuting on studded tires had honed our winter-biking skills, but we’d never taken an ice-biking camping trip across the surface of a lake.

We decided to explore the landscape north of Winston. Visible by boat in summer, but lacking public-road access, the only way there this time of year was over the ice. Parking at the White Earth campground, we loaded up our BOB trailers with enough gear, water, and food for a comfortable evening in the single digits.

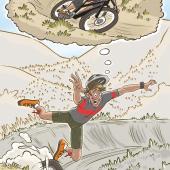

Rolling down the boat ramp onto the ice was the moment of truth. For those who have never ventured out on big ice, the experience is both exhilarating and terrifying. Leave the perceived safety of shore and you’re immediately suspended above a frosty death by only a transparent and temporary mixture of hydrogen and oxygen. And this vision never completely leaves your mind while you’re out there.

We pedaled north along tan-colored bluffs that eventually opened up to a broken landscape of gullies, eroded hoodoos, cottonwood bottoms, junipers, and sage. We quickly left behind any indications of human activity. Whether for lack of fish or rough ice, there were no fishermen, skaters, or ice-boaters on this section of the lake. We rolled along, alone in what felt like the middle of nowhere.

Every undulation in the shoreline produced a change in the ice’s surface, whether it had been sheltered from the wind or not. Some sections were glass-smooth and slippery, others had a skiff of snow and surprisingly good traction. One expanse of refrozen chunks looked like a sea of shark fins—which made for especially technical and treacherous riding. The patterns of shuga ice, newly formed in agitated conditions, were varied like endless translucent Rorschach inkblot tests. Coyote tracks crisscrossed between sections of land, while dead fish lay frozen on the lake’s surface.

It’s difficult to say what was more disconcerting: the crack and boom of ice flexing and shifting as temperatures changed, or the random pockets of open water that had to be identified and given a respectfully wide berth. Sometimes a gunshot-like echo would rip across the frozen plane. Other times a haunting tone like some siren’s call screamed from the depths.

After miles of shoreline exploration, we rolled into a sheltered bay that offered a good camping beach with plenty of driftwood for a roaring fire. Over dinner, we were treated to an alpenglow-sunset view of Baldy and Edith, the frosted twin peaks of the Little Belt Mountains on the opposite side of the lake, as dusk gave way to a starry night.