Shoulder Season

Kayak and canoe paddles, bike wheels, bare backs in the sun. Aaah, Bozeman in the springtime. It really is paradise here in southwest Montana… until that darn rotator cuff injury ruins everything! Shoulder issues are so common that it seems like everyone and their dog has one. Let’s take a closer look at the shoulder and get you moving freely this “shoulder season”.

It helps to think of the shoulder as two main structures. One is the ball-and-socket joint where the head of the arm bone (humerus) rests in the shoulder blade (scapula). The other is the shoulder blade itself. The two move independently, yet connect to and affect each other. The collarbone (clavicle) is also part of the shoulder, as well as surrounding tendons, ligaments, muscles, and other soft tissues.

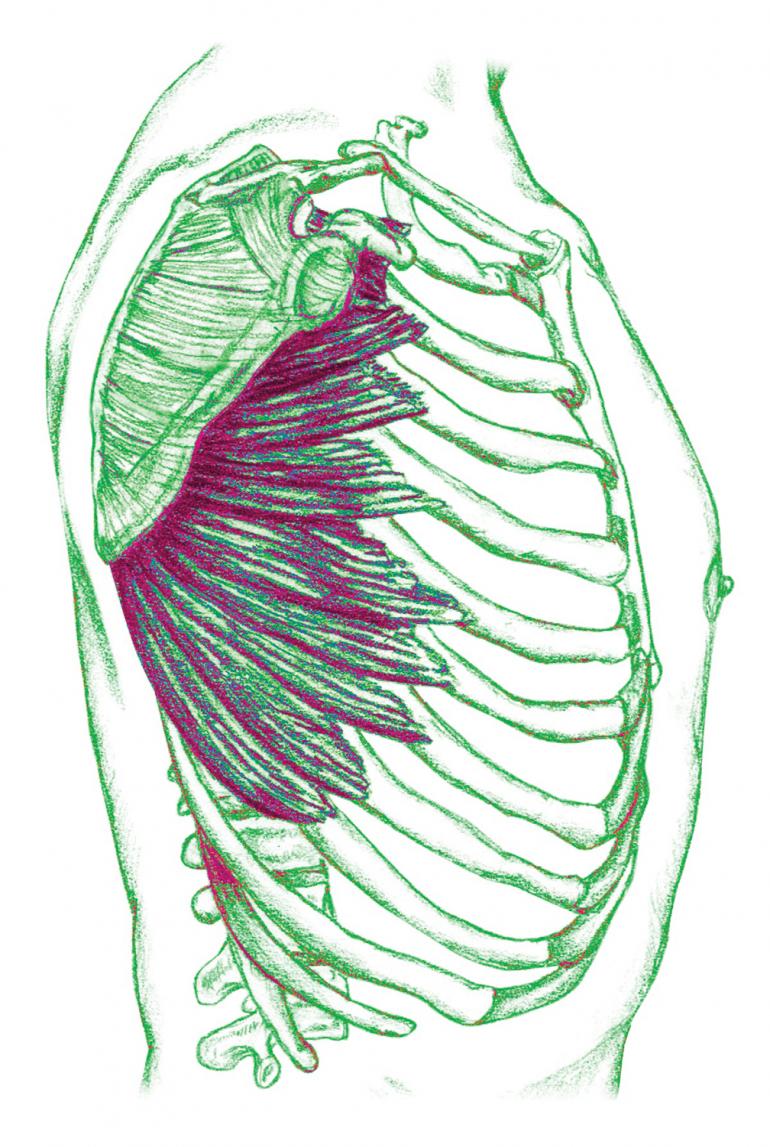

The rotator cuff is made of four tendons that attach on top of the arm bone. They move the ball-and-socket joint and help hold it in place. The four muscles whose tendons comprise the rotator cuff originate in the back of the body on the shoulder blade.

Why is the rotator cuff easily injured? To allow greater mobility, these tendons are somewhat loose and the ball rests in a shallow socket, leaving the joint vulnerable. We have many more muscles pulling the arm forward and inward than we do holding it upright—3:1 in the rotator cuff. Slouching posture and our forward-reaching outdoor activities create even greater instability.

So what is ideal alignment? The shoulder blades should rest on the back like two parallel plates facing forward while the heads of the arm bones root deeply in their sockets. Roughly, shoulders should line up with ears, hips, knees and ankles, all stacking atop one another. (Yes, really.)

When it’s time for outside help, who should you see? Scott Gill, a PA at Bozeman Urgent Care, tells us there is potential success in everything—and that our own belief can greatly affect our healing ability. He says rotator cuff injuries are hard to nail down. X-rays and MRIs are especially helpful for diagnosis—but he can’t give them to everyone. In the case of injuries like partial tears and tendonitis, he often recommends physical therapists specializing in the shoulder and says that patients often bounce back quickly. More severe injuries may need the help of a surgeon.

Gill often recommends physical therapy as a good first option for treating a shoulder injury, which is also cheaper than a surgeon. Ultimately his advice is to find a practitioner who really listens and directs you to treatment that’s right for you.

There are multiple approaches to shoulder (and whole) health. Gill sums it up when he says we all have the patient’s best interest at heart (hopefully!), so pick a provider, do your own alignment work, get well… and go huck yourself off a cliff.

Jenny LePage is a massage therapist and owner of Bozeman Massage Therapy, an eco-friendly business in downtown Bozeman. She can be reached at bozemanmassagetherapy.com.

Rotator Cuff Exercises

Shoulder Alignment

Start with arms in front of you in a V shape. Disengage by pulling shoulders forward. Align by pulling the heads of the arm bones into their sockets and moving shoulder blades together on the back.

Wall Angels

With you feet about four inches from the wall, stand against a wall and slowly move arms overhead. Shoulder blades and arms should touch the wall the whole time—work it! This can be done lying down—bend the knees to prevent any lower-back discomfort.

Wall Push-Ups

Place your hands on the wall like a plank pose in yoga: middle fingers pointing up, the rest spreading open and all parts of the hand equally touching the wall. Sense the wall, pushing only as much as the wall is pushing back; notice how this engages the serratus. Touch your nose against the wall while hugging elbows in and hold for five to seven seconds. —Jenny LePage