Visitors in an Untrammeled Land

Class IV means churning rapids, dangerous rocks, and high waves. Anything less than powerful and precise maneuvers means swimming—or worse. And “Wilderness” means no cell phone service, no roads, and no real easy way to fix a disaster. “If the raft flips or gets pinned sideways against a rock, you’re gonna want to get clear of it,” Mike Fiebig says. “Keep your feet up and point ‘em downstream.” We’re going over safety protocol for our trip through the upcoming whitewater, but as the associate director of American Rivers, Mike probably won’t get us into trouble.

Probably.

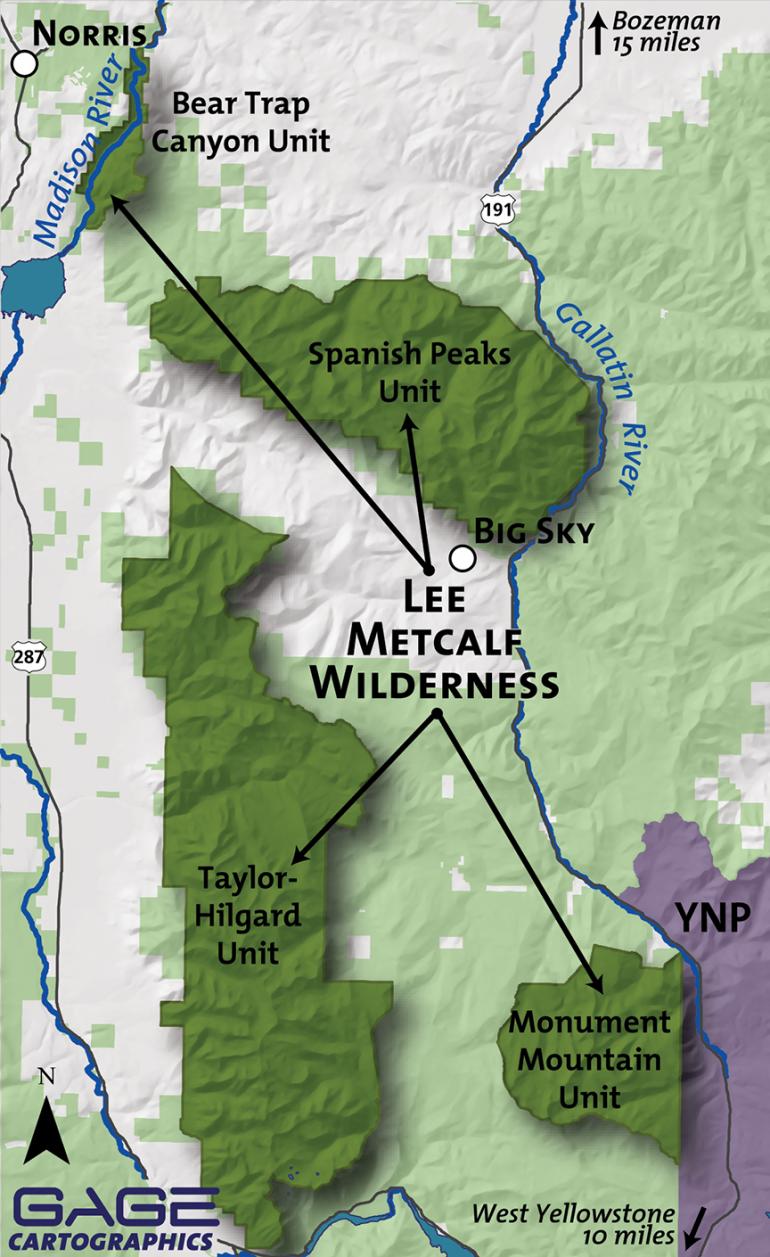

On the 30th anniversary of the Metcalf Wilderness, the plan is to float and fish Bear Trap Canyon: the nine-mile stretch running through the northernmost of the four components of Wilderness designated in honor of the late statesman and conservationist Lee Metcalf. All told, the Metcalf Wilderness is comprised of over 259,000 acres of wild, roadless land across the Madison Range in southwest Montana.

With us is Jared White from the Wilderness Society, and Bill Cunningham, a personal friend of Metcalf and an advocate of his Wilderness bill. In 1984, to commemorate the nation’s first Wilderness designation on BLM land, Bill floated the Bear Trap with Metcalf’s widow, Donna, and then–Secretary of the Interior William Clark during record flows. The group dumped a raft right in the middle of the Kitchen Sink, and Bill hasn’t been back to the Bear Trap until today. We’re hoping this time through will be a little less harrowing.

Defined by the Wilderness Act of 1964, Wilderness is “an area where the earth and community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Another key factor is the means of travel you can use—no mechanized travel allowed. If you want through, it’s by boat, by foot, or by horse.

I’d heard of this stretch of Wilderness, but never visited it. The sands of time had eroded away the stories and only left the name: Lee Metcalf. To my generation, those two words were shapeless adjectives in front of a Wilderness designation. Like Bob Marshall. Frank Church. John Muir. Turns out, Metcalf would have wanted it that way. He often avoided the spotlight, and he’d usually try to hand out credit instead of taking it. Outside the Treasure State, almost no one knew his name—he didn’t even have a press secretary. But as Montana’s first native-born senator, he spent his time in the US Congress working to protect the nation’s airways and watersheds, cosponsoring the Clean Air Act of 1963, the Water Quality Act of 1965, and the Solid Waste Disposal Act of 1965, among plenty of others. Some call him the Patron Saint of Wilderness—a fitting title for a man that spent 15 years fighting tirelessly for conservation.

We go around the group, introducing ourselves and shaking hands. We haul our crafts down to the water. We shove off down the river, and once we’ve rigged the fly rods and settled into the boat, it hits me: there’s nothing here. No campsites, no roads, no power lines—only skyscrapers of rock on each side of the canyon, quilted in junipers and ponderosas. In the first few miles, there are more bald eagles than people on the water. The only sign of civilization is a hiking path following the river—and even that is little more than a game trail. The canyon looks exactly as it did 5,000 years ago, and as a Wilderness Area, it should look exactly the same in another 5,000. It seemed hard to believe that an area so wild and isolated could begin at the north end of Ennis Lake—a bustling hub for powerboats and cliff jumpers—and end at the Warm Springs take out, which is ground zero for the summertime bikini hatch and thousands of trout-chasing drift boats.

Even more unfamiliar is that there’s no sound beyond the calm flow of water, the occasional dip of the paddle, the buzz of drag on a fly line. “How often do people spend time like this?” I ask Bill. He laughs.

“For 98 percent of the population, probably never,” he says.

He could be right. In our world of concrete and glass, it’s safe to say that the majority of us have spent our entire lives on artificially constructed turf. We exist in structures built by people, surrounded by people. As a species, humans have spent far more time walking on dirt than on pavement, and to ignore our 200,000-year relationship with Mother Nature is shortsighted at best, dangerous at worst. Some people think America’s soaring rates of depression and anxiety disorders have to do with our diminishing connection to nature. Wilderness Areas might not cure anyone, but it’s awfully hard to frown while reeling in a fat rainbow on a tranquil river.

“I got another one!” Bill says, pulling his third trout into the raft. We’re throwing fat brown crayfish with nymph droppers, but as soon as we spot the first set of rings on the water, we switch to #16 dry flies—little more than tufts of fur hiding a hook inside. The water starts popping with rises like someone on shore is throwing handfuls of gravel, so each raft runs laps past the hot stretch, pulling in trout after trout. Echoing up the canyon, laughter rises like bubbles in boiling water. The water’s clean, so you can track each fish giving a few lazy kicks and biting at the surface. “Oh… oh… two in the boat!” someone yells as big loops of neon swirl around overhead.

The fishing cools down, and we pull the rafts to shore just before the Sink. After lunch, we hike around to scope the rapids, waders swishing and brambles clawing at our shirts. The gentle trickle of water changes to a roar when we hike down to the river’s edge, thousands of gallons of cold water crashing over the jagged rocks. “She’s a little bony,” Mike says, pointing to a notch between two boulders. “That’ll be the route through. It’s a shallow Class IV, but still exciting.” He turns to me. “I can fit two in my boat. You wanna come with?”

Deep in my gut, there’s that bite of nerves. The tension, the pressure building from fear and adrenaline and potential death. My mouth tastes like nickels. There are only two ways to release that pressure building inside: let it vent off as hot air and excuses and stay on the riverbank, or stretch out my comfort zone to accommodate the extra PSI and get in the boat.

“Uh… I have to take pictures,” I say.

Mike rolls his eyes and hikes back up the trail. The rafts make it through clean. Mike’s so damn good at rowing, everyone in his boat looks bored.

Ten minutes past the rapids, we pull to the bank and open the cooler. We raise our cans of beer. “To Lee,” Mike says. We answer back as a chorus, “To Lee.” We give an impromptu moment of silence, drinking our microbrews and watching the river flow around us. Saying I can feel Metcalf’s presence is closer to truth than cliché. On January 12, 1978, Lee Metcalf died in Helena. He was cremated and spread across the Wilderness Areas he loved so much. “It’s funny to think what this place would look like without Lee,” Bill says. “There’d probably be a road here, power lines, benches, signs…”

He’s right again. We can always build more stuff, create more things. But we can never, ever make more nature. We can only save it—and we should be thankful that Metcalf saw that reality and applied it to Montana in time.

As we reach one of the final bends in the river, I ask Bill if he’s disappointed that nothing has happened on the Wilderness front in 30 years. “We just shouldn’t lose heart. Shouldn’t give up,” Bill says, casting a nymph and mending the line. “We haven’t gained any Wilderness, but we haven’t lost any either. That’s a win in my book.”

That was one of the many gifts that Metcalf gave the people of Montana: thanks to the wording in his Montana Wilderness Study Act, a Wilderness Study Area (WSA) must managed to protect its value as Wilderness. Essentially, if it’s being studied, the area becomes de facto Wilderness.

“Wilderness is supposed to be forever, and so should our commitment be forever. We owe it to our kids,” Bill says, smiling. “I always say that conservation requires ‘endless pressure, endlessly applied’ to be effective.”

Jared paddles over in his packraft. “You know, the Metcalf-era conservationists are getting old—no offense Bill—but there’s a new generation of people on the verge of moving Wilderness forward,” he says. “It’s a sign of hope.”

Montana’s 30-year Wilderness dry spell might soon be coming to an end. The Rocky Mountain Front near Choteau has nearly 300,000 acres ready for Wilderness designation. The Gallatin Crest just south of Bozeman is a 250-square-mile WSA, and the community is coming together to find a solution for access. And one of the areas that Lee Metcalf had wanted to see protected before his death, Cowboy Heaven, still has a shot to be tacked onto Senator Tester’s Forest Jobs and Recreation Act. The bill proposes to link the Bear Trap Canyon piece with the Taylor-Hilgard Unit, currently separated by a dozen miles of national forest.

We hit the Warm Springs takeout, coming back to reality. We drag the rafts up the concrete ramp as cars buzz down the highway. Power lines stretch across the blue sky. A white-trash couple smokes cigarettes in the back of a pickup—and God, I wanna be back in the woods already. Thanks to the efforts of men like Lee Metcalf and Bill Cunningham, and the continued work of men like Jared White and Mike Fiebig, I can go back. We can all go back as visitors to these beautiful, untrammeled lands for generations to come.

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of Montana’s first wilderness designation, the Wilderness Society is pulling out all the stops to honor Lee Metcalf and his hard work. For more information and to RSVP for events, go to summeroflee.com—you’ll find times and locations for their hikes, farmers’ markets, and other events throughout the “Summer of Lee.”

June 22 – Spanish Creek hike

July 12 – Spanish Creek trail work and weed pull

July 18 – High lakes campsite occupant survey training, Bozeman

July 20 – Bacon Rind hike

July 20 – The Helmet hike

July 25 – High lakes survey campsite occupant training, Big Sky

July 27 – Monument Meadows hike

Aug 2 – Cache Creek (Taylor Fork) trail work and weed pull

Aug 17 – Papoose Creek and Cradle Lake hike

Aug 17 – Cycle Greater Yellowstone, West Yellowstone

Aug 18 – Cycle Greater Yellowstone, Ennis

Sept 7 – Bacon Rind trail work and weed pull

Oct 4 – “Summer of Lee” wrap party