A Rift Runs Through It

Fighting for access to the Ruby River.

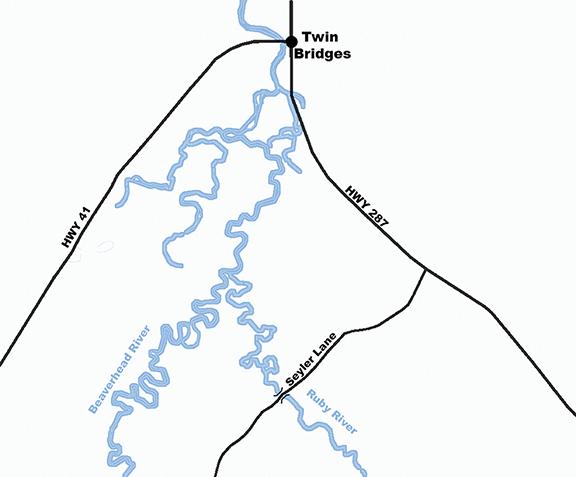

Seyler Lane isn’t much of a road. It isn’t even much of a lane, and chances are most of us never would have heard of it except for three accidents of geography. First, Seyler Lane is a public road with an established prescriptive easement. Second, it crosses the Ruby River by way of a bridge, a popular point of river access for anglers and recreational floaters. Third, the land surrounding the bridge is owned by James Cox Kennedy. Couple these facts with Kennedy’s wealth and arrogance and pit them against the determination of a small group of Montanans daring enough to believe that the public should actually be able to utilize public resources, and you have the makings of a legal storm that has rocked the state to its core.

The legal history will emerge in due course. Since I don’t like reading court cases any more than you do, let’s meet the cast of characters first.

Wearing the white hat—Montana’s very own Public Land and Water Access Association (PLWA from here on in), a group of unpaid volunteers that for years has played a crucial role in reopening illegally blocked access to public lands and waters throughout the state. Most Montanans wouldn’t realize how much public land access has been denied this way save for efforts by PLWA. Although basically a ragtag guerilla group fighting an odds-against battle against powerful, well-financed interests, its record of success in the courts has been remarkable.

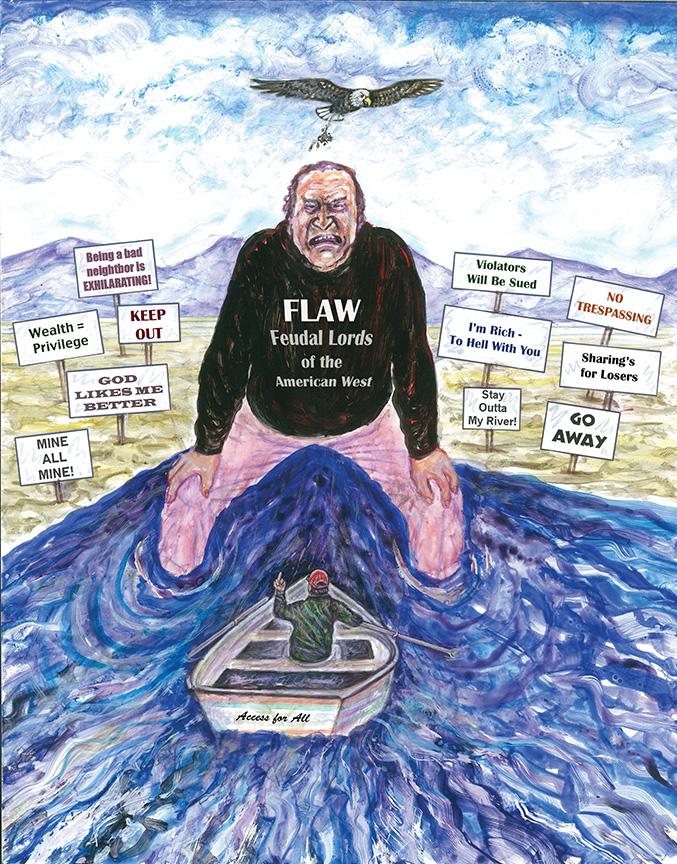

Wearing the black hat—Media mogul Kennedy, chairman of Atlanta-based Cox Enterprises, 49th wealthiest individual in the country (per Forbes, 2008), but ultimately a selfish man who inherited his assets and would be of little consequence except for the staggering number of zeros on the numbers at the end of his bank account statements. In fairness—which isn’t easy—his online biography credits him with a number of philanthropic undertakings, including some that have been good for wildlife and the environment. Why he chose to check these values at the border when he entered Montana remains a mystery.

The issue—Kennedy’s apparent belief that a remarkable body of Montana law establishing the public’s right to recreate freely on the state’s waterways does not apply to rich people. It’s really that simple.

A Brief History of Stream Access

In 1979, two Butte anglers concerned about landowner harassment on nearby streams consulted with Bozeman attorney Jim Goetz. Their efforts eventually resulted in the creation of the Montana Coalition for Stream Access, Inc. (MCSAI), which became the Public Land Access Association in 1986, which in turn became the Public Land and Water Access Association in 2007.

In 1977, future MCSAI members filed suit against a landowner along the Dearborn River who was harassing recreational floaters. (The landowner was a distant relative of my wife, Lori. What a family I married into!) MCSAI v. Curran wound up in the Montana Supreme Court in 1984, at which time the court ruled, citing the ancient public-trust doctrine, that “any surface waters capable of use for recreational purposes are available for such use by the public.”

A second key case arose when PLWA brought suit against a landowner threatening to string a cable across the Beaverhead River to prevent recreational floating. Again in 1984, the court ruled in MCSAI v. Hildreth that if the stream is navigable for recreational purposes it can be used as such up to the high water marks without regard to ownership of surrounding land.

These cases provided the background for a crucial piece of legislation: Montana’s 1985 Stream Access Law. The bill was drafted with input from many stakeholders including landowners and received broad bipartisan support (remember that concept?). Subsequently, a group led by Martinsdale rancher Jack Galt asked the district court to find the law unconstitutional. When the court ruled against the landowners, they appealed to the Montana Supreme Court, which upheld all major provisions of the law, now regarded as one of the most enlightened and progressive statutes of its kind in the nation.

Further challenges were probably inevitable. Disgruntled landowners filed suits to overturn the law in 2000 and 2001. District court upheld the law, as did the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals on both occasions.

Case settled, right? Wrong—you still have to reach the stream in order to float it.

Screw You, I’m Rich

Prior to Cox’s purchase of his trophy ranch along the Ruby, the Seyler Lane bridge and two others provided river access to a wide cross-section of outdoor recreationists ranging from visiting anglers carrying thousand-dollar fly rods to college students toting six-packs of beer to sustain them during long floats on hot summer days. No one ever questioned Kennedy’s right to privacy on his adjoining land. But Montana law established public right to the water, and original owner Bud Seyler hadn’t challenged public river access from the bridge, creating a “prescriptive easement.” Furthermore, in 2000, state attorney general Joseph Mazurek issued an opinion stating that the public may gain access to streams and rivers by using a bridge, its right of way, and abutments, and that the road easement does not narrow at a bridge.

But not according to Kennedy, who began to physically bar access by erecting barbed wire and electric fences across the easement between the bridge and the water in 2003. When Madison County refused to remove the barriers, PLWA filed suit in 2004 to establish public access via three bridges across the Ruby, including Seyler Lane. Kennedy joined the fray in 2007, asking the court to bar all access at the bridges. Judge Loren Tucker found in favor of PLWA on two of the bridges, but delayed a ruling on Seyler Lane for procedural reasons.

Meanwhile, the legislature recognized the need to clarify this contentious issue. The result was the 2009 Bridge Access Law, stating that the public must be allowed to access streams and rivers from public roads and bridges and establishing a legal protocol for resolving disputes. It’s remarkable that a legal team as well-paid as Kennedy’s evidently managed to overlook this statute.

In 2012, Judge Tucker issued a delayed ruling on the Seyler Lane portion of the original lawsuit. The public had been crossing the Ruby at Seyler Lane for a hundred years. Furthermore, the county maintained the road and built the bridge. The existence of a prescriptive easement was not in question. The case turned on what the easement allowed. The lower court ruled against PLWA via a tortuous opinion that no one really understood, holding that two separate easements existed but neither provided legal access to the river. PLWA appealed. The Montana Supreme Court rejected Judge Tucker’s two easement theory and directed him to establish Seyler Lane as a safe and convenient travel route.

The legal maneuvering grew even more complex when Kennedy cross-appealed in order to attack the validity of the Montana Stream Access law itself, which he claimed represented an unconstitutional “taking.” During argument, Supreme Court Justice Patricia Cotter pointed out that the Montana constitution states “all the waters are the property of the state for the use of its people,” and asked Cox’s attorney if he was requesting the court to declare the state constitution unconstitutional. The answer was: “Yes.” Hmmm… an unconstitutional constitution? Where would rich people be without lawyers?

In 2014, the Montana Supreme Court issued a unanimous opinion upholding the Stream Access Law and clarifying the public’s use of rights-of-way. In a separate 5-2 decision, they also rejected Judge Tucker’s two-easement theory of the Seyler Lane access case and remanded the matter back to district court for resolution. PLWA attorney Devlan Geddes called the decision one of the most important public-road legal rulings ever made in the state.

The next district-court hearing was held on August 3, 2015. Those of us hoping for a definitive resolution should have known better. Procedural maneuvers delayed a ruling, which is now scheduled for mid-September. That’s where matters stand as of this writing. I am not holding my breath. In court, delaying tactics always benefit the side with the deepest pockets. The 12-year record outlined above speaks for itself.

Beyond the Ruby

Most Montanans familiar with the Seyler Lane saga recognize that the dispute is about more than the ability to slide a raft into the Ruby River. James Cox Kennedy—arguably the most unpopular man in southwestern Montana—took an assault on the state’s popular Stream Access Law all the way to the Supreme Court despite abundant legal precedent upholding this legislation. He and his legal team must have known that their chances of victory were remote—Kennedy’s shortcomings are ethical, not intellectual. The cost of litigation must have been substantial, although it likely represented little more than cookie-jar money to him. Montana taxpayers bore their own share of the cost of this spiteful suit, for a Supreme Court does not run on fumes. Meanwhile, PLWA continues to thrive on volunteer effort and small contributions from people who cling to the notion that the public has rights, and that despite the odds, big money will not always prevail in the end.

Kennedy’s legal maneuvering makes it clear that he would love to see Montana’s Stream Access Law go away. The most feasible strategy for accomplishing that goal is to outspend the opposition and litigate it to death with teams of lawyers, dispatching them on command like the Wicked Witch of the West unleashing her winged monkeys on the Land of Oz.

He has the means to do it. PLWA is an underfunded grassroots organization driven by the energy of people who care. Readers concerned about their future ability to enjoy Montana’s outdoors—the reason why most of us live here in the first place—can visit plwa.org to find out how to help.

And enjoy the fishing—if you can still get to it.