Sphinx Mountain

With its blocky shape, truncated summit, and unique color, Sphinx Mountain has drawn more climbers to its summit than any other major peak in the Madison Range. This fortress of reddish-brown conglomerate is one of the most distinctive landmarks in the Yellowstone area, and the deep encircling canyons of Indian and Bear creeks segregate Sphinx Mountain west of the Madison Range crest. Nevertheless, the summit’s registers reveal that over 200 climbers reached the top between 1913 and 1976, and many more have climbed the mountain since then.

Sphinx Mountain is also the only peak in the range consisting of the mysterious Sphinx conglomerate. Little is known about the age or origin of this post-Mesozoic deposit, which creates the top 2,000 feet of the mountain. Similar outcrops of conglomerate are in the Gravelly Range across the Madison Valley and in the mountains east of Jackson Hole, but none are exactly like the Sphinx rock. This peculiarity is what drew students from the Harvard Summer School of Geology to the area in the 1910s to make at least two ascents, the first of which was on July 30, 1913, by Anton W. Asmuth, George Belchic, Stanley H. Wardwell, and someone named Kimball. On August 1, 1919, a second group consisting of R. B. Hevy, John H. Hall Jr., Robert E. Crosby, and Henry J. Hall Jr. recorded an ascent. They reported an undated summit register with the names of Japanese climbers who might have been guests at a Madison Valley dude ranch.

Henry Hall, who had just served a year and a half in Europe during World War I, would go on to become one of the most influential climbers of the early twentieth century, with landmark ascents in Canada’s Coast Range, the Canadian Rockies, European Alps, Africa, New Zealand, and South America. He also would spend some time during the 1920s climbing in the Tetons and Wind Rivers with regular partners Robert Underhill and Kenneth Henderson.

The Harvard students probably were not the first scientists to be interested in Sphinx Mountain. Frank Tweedy or Edward Douglas may have climbed Sphinx as early as 1886 during their topographic survey of the Three Forks quadrangle, which labels the mountain as “The Sphynx.” Hayden Survey veteran Albert C. Peale also may have climbed the mountain around 1890 during his geologic survey of that same quadrangle.

Since the first recorded winter ascent by Kit Jones and James W. Clark on December 30, 1964, Sphinx also has been a popular winter climb. Dave and Richard Klatt, along with partners Jon Todd and George Clagett, climbed Sphinx twice during the winters of 1969 and 1970. On March 16, 1974, Frank J. Wilson, Jerry Stolle, and Bob Fitch reached the top. Rick Reese also made two winter trips to the top in January 1983 and February 1984.

Since the first ascent, the treacherous-looking cobblestone cliffs that rim all but the west side of the mountain channeled everyone into the west gully and west ridge—until Patrick Whelan solo-climbed the south face in 12 hours on May 10, 1969. Whelan scrambled most of the way up this 1,500-foot wall and used “pitons and two six-foot ladders” to overcome the final steep headwall.

In late autumn of 1987, Bozeman climbers Alex and Jennifer Lowe were the next to pioneer a new route on the mountain. Spotting ice streaks from Lone Mountain, the couple tackled the nearly 2,000-foot concave north face. When the route is in good condition, it begins with numerous ice-coated striated cliff bands that offer little protection. It involves at least one difficult vertical pillar and finishes with steep, thin ice in the only couloir that penetrates the vertical 400-foot summit cliff. In Big Sky Ice, which rates the route Grade V WI4+, Geoff Heath describes this ascent with Dougal McCarty: “Most of our climb involved short pitches of rock followed by traverses along steep snow bands to the easiest looking way through the next rock barrier. The snow was loose powder, difficult to get around in… The big surprise was that the rock turned out to be of fairly good quality conglomerate.” Kris Erickson solo-climbed Lowe’s north face route in 12 hours in the late 1990s.

In the late autumn of 1997, Tom Kalakay and Kirby Spangler established another climb, called “The Riddle” (Y.D.S. IV 5.9 WI5+), on the steep wall well to the right of Lowe’s route. Other ice lines also may have had ascents as well.

In March 1999, Hans Saari and Kris Erickson actually skied Lowe’s route, dubbing it “The Sphinxter.” Completed in 11 hours round-trip, their descent entailed steep shallow snow over ice, technical maneuvering through cliffs, and two rappels. Most glisse mountaineering on Sphinx Mountain occurs on the west face, where tracks are visible every spring. As snow melts throughout the spring, the strip of snow gets narrower.

Alex Lowe Hans Saari

Sphinx Mountain Ascent

Bear Creek parking elevation: 6,400 feet

Elevation gain: 4,476 feet

Distance (one way): 7 miles

Overall grade by west ridge: II Class 3

Estimated ascent time: 3 to 6 hours

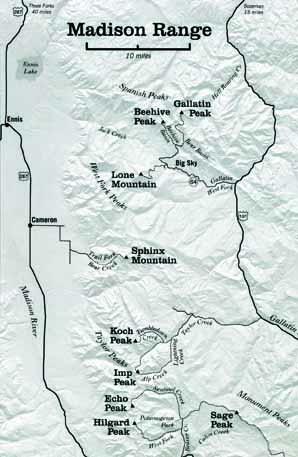

Maps: Lake Cameron, Sphinx Mountain

Getting There

From Highway 287 at Cameron, head east onto a dirt road and turn right after three miles. Follow this bumpy road through two 90-degree turns, past ranch houses, then turn left to the mouth of Bear Canyon. Park near a ranger station.

Hike on a superb trail for approximately five miles, bearing left at one junction, to the saddle between the Helmet and Sphinx Mountain. Follow the climbing trail along the ridge toward the mountain and traverse across loose scree through a break in the horizontal cliff band that guards the bottom of the face.

In early season, follow snow in the main drainage to the summit. If the snow is gone, continue traversing across the face's main drainage to the broad scenic west ridge, which is south of the drainage. Follow this long ridge to the summit over several conglomerate steps and slabs near the top.

Although Sphinx scree is as exasperating as any other, Shpinx conglomerate cliffs offer surprisingly solid climbing, albeit with little protection. A rope is not needed for the west ridge if you pay attention to route-finding. There is little or no scree and excellent footing. For the descent, glissade snow in the main drainage. If the snow is gone, resist the temptation to descend the difficult scree north of the main drainage. This area has fragile moss, grass, and soil that should not be disturbed. Instead, follow the steep scree trails down the sides of the drainage or climb down the west ridge.

This is excerpted from Select Peaks of Greater Yellowstone, the authoritative guide to hiking, climbing, and skiing the mountains of southwest Montana. It is currently out of print but a new edition is in the works.