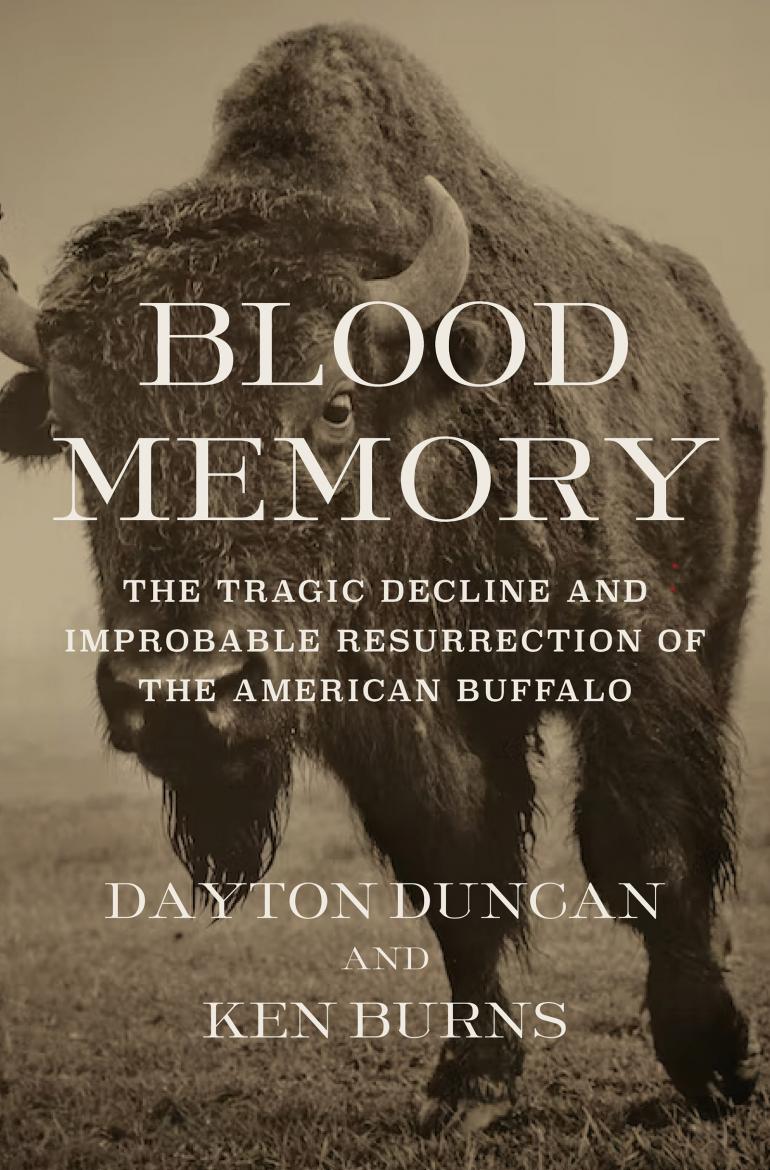

Blood Memory

The tragic decline and improbable resurrection of the American buffalo.

Driving north on I-90, across the plains of eastern Montana, one passes through Crow Indian country. Spending a day or two on the Crow reservation for the annual Crow Fair allows a visitor to see colorful native horsemen and horsewomen, hundreds of dancers, and some of the best drum groups from around North America celebrating their culture in a 1,000-tepee village on the Little Big Horn River.

In the tribal dance arbor, you feel the power of the drums and the pain of the Native Americans’ cultural losses as they sing tribal songs and prayers, celebrating their ancestral existence with a big, shaggy relative, once sharing the plains with them in the millions.

In just a 20-year span, from 1870s to the 1890s, the Native Americans lost their most important resource: the buffalo. Today, mostly treeless grasslands stretch as far as you can see to the horizon, but this large mammal is conspicuously missing. How did we go from millions of buffalo to less than 1,000 in just a generation?

Manifest Destiny drove European-American settlers westward, and Native Americans and buffalo were in the way. As Montana author Wallace Stegner wrote, “We are the most dangerous species of life on the planet, and every other species, even the Earth itself, has cause to fear our power to exterminate.”

More recently, Dayton Duncan and Ken Burns have collaborated on a new PBS television series, The American Buffalo, and have written a companion book entitled Blood Memory: The Tragic Decline and Improbable Resurrection of the American Buffalo. Together, they are a fitting tribute to the buffalo, telling a compelling story from the time of the Lewis & Clark Expedition to the animal’s near-extinction and almost-impossible recovery.

In just a 20-year span, from 1870s to the 1890s, the Native Americans lost their most important resource: the buffalo.

Duncan details a sobering look at how we almost lost America’s most iconic mammal through greed and human nature. His lifelong fascination with the West was inspired by retracing the 1804-1806 route of the Lewis & Clark Expedition.

“My journey along Lewis & Clark’s trail changed my life,” Duncan remembers as he describes his first taste of buffalo from an unforgettable Mandan-Hidatsa man: six feet, five inches tall, with his long hair in braids dangling to his shoulders. After killing a rogue buffalo that wandered from Theodore Roosevelt National Park, the man offered him a big knife with a glistening hunk of raw liver. Today, after four decades of friendship, they are still “buffalo brothers.”

Another buffalo brother, George Horse Capture, who operates Aaniiih Nakota Tours at the Ft. Belknap Reservation in Montana, is an interviewee in the series. He says, “Everything had to get out of the way. When Europeans came, everything that was natural had to get out of the way.”

And it was more than just buffalo. Native peoples, wolves, and grizzlies were all threats to the takeover. “The buffalo were the life of the Kiowa,” says Kiowa poet N. Scott Momaday. “Everything the Kiowas had came from the buffalo. Their tepees were made of buffalo hides. So were their clothes and moccasins. They ate buffalo meat. Most of all the buffalo was part of the Kiowa religion. The priests used parts of the buffalo to make their prayers when they healed people or when they sang to the powers above.”

Dan Flores, a western-history professor at the University of Montana, echoes the sentiment: “Native Americans suffered inexcusable collateral damage consciously done to the people so dependent on that animal for their physical and spiritual survival.” The buffalo almost didn’t survive. Remarkably, however, the species pulled through.

“The American buffalo was saved from extinction, but still faces challenges to its long-term future,” Duncan explains. “The story of the American buffalo is unfinished and still being written, taking new turns, facing new challenges, and offering more lessons yet to be fully learned.”

The buffalo almost didn’t survive.

Native peoples now oversee more than 20,000 buffalo, and the herds are still growing. A plan to share stewardship of Yellowstone National Park’s bison between tribes and federal agencies is being proposed by a Montana bison advocacy group, the Buffalo Field Campaign (BFC). The group’s executive director, James Holt Sr. (a Nez Perce member), mailed a letter on June 16, 2023 to 31 tribes proposing a summit in November at Fort Hall, Idaho, to discuss the idea. “The time has come for Tribal Nations to come together, to share our hearts and unite on behalf of Yellowstone Buffalo,” Holt wrote in the letter. “Tribes must not settle for 6,000 wild buffalo when management should target populations of 50,000 or more. Tribes must not settle for a few thousand barren acres outside Yellowstone National Park, when buffalo should have access to 8 million adjacent acres of suitable habitat on open and unclaimed federal lands.”

BFC also said in a press release that including tribes in bison management would be the “beginning of ‘true reparations’ for the long-standing practice of cultural genocide, or ethnocide, that is still being perpetuated by the cattle industry to preserve their monopoly on public lands forage in the West.” The statement goes on to specifically target the Montana Department of Livestock for its involvement in bison management (bison are the only wildlife species in the state overseen by the agency).

Montana Governor Greg Gianforte, however, and many Montana cattlemen are strongly opposed to the re-wilding of buffalo in Montana. To understand why, I reached out to the Montana Stockgrowers Association, the Montana Department of Livestock, and the governor’s office. None responded.

Montana governor Greg Gianforte and many Montana cattlemen are strongly opposed to the re-wilding of buffalo in Montana.

Fortunately, private organizations are taking efforts into their own hands. The Nature Conservancy, the Wildlife Conservation Society, and American Prairie are all working to give buffalo more room to roam. Notable in their work is American Prairie’s re-wilding program, which aims to fully restore the shortgrass prairie ecosystem by assembling a land base of 5,000 square miles encompassing the 1.1 million Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and surrounding private lands.

After decades of writing and producing PBS documentaries about the American West, Dayton Duncan has created a memorable way to end his PBS career with The American Buffalo. His love for Lewis and Clark, bison, and Native Americans is inspiring to watch and read. “One of the main themes of the buffalo is resilience," Burns explained in a recent podcast. "And that’s a really powerful thing,”

So let’s all work together to find a way to re-wild the Great Plains and a create a chance for bison to once again run wild and free. We owe it to our grandchildren and for generations to come. Let your public officials know that a future with buffalo running wild should be our goal. Like Gerard Baker says, “the buffalo don’t want to come back as cows.”

The American Buffalo is directed by Ken Burns, written by Dayton Duncan, and produced by Julie Dunfey. It’s available on PBS. The book Blood Memory can be purchased here.