Road Trip: First Peoples Buffalo Jump State Park

Exploring the traditions of those who came before.

The north-central prairie above the Missouri River looks like a Charles M. Russell painting. Fields of bluebunch wheatgrass interspersed with needle and thread, blue grama, and prickly pear cactus lead to high bluffs, which are home to whitetail deer, antelope, and prairie dogs. Historically, wild buffalo roamed these lands as well. While bison numbers have drastically decreased, they remain a true, not so ancient, icon of the American West.

The bison's current existence has been reduced to the confines of areas like the American Prairie Reserve and Yellowstone National Park, and much of the plains’ native flora has been replaced by wheat, barley, and alfalfa. But outside of the sleepy town of Ulm in Cascade County, if you head west on Taft Hill Rd. and pass through the patchwork of stubble and fallow fields to First Peoples Buffalo Jump State Park, you’ll come upon the same ground that inspired Charlie Russell to paint a hundred years ago.

To get to the 1,480-acre park, travel north from Helena on I-15 through Wolf Creek Canyon into the vast steppe of central Montana. Exit at Ulm and travel west for 3.5 miles to the entrance. Rising out of the river bottom, the first distinctive topography you come to is a mile-long sandstone cliff, anywhere from 30 to 50 feet high at any given point. Native Americans called this “pishkun,” a Blackfoot word meaning "deep blood kettle." It's one of the largest buffalo jumps in North America; at least seven tribes used it routinely.

A buffalo drive could start as far as a mile away, where members of the tribe began herding the animals toward the drop. Awaiting the stampeding arrival were Indian braves known as “runners” clothed in buffalo hides. In disguise, runners would lead the incoming herd to the cliff’s edge, then drop over the precipice to shelves or concavities in the bluff. The tricked beasts would follow at high speeds, coaxed into a blind and bloody death-inducing tumble.

Archaeologists estimate this particular pishkun to be at least 1,500 years old, with the heaviest signs of use around 1,000 years ago. On top of the cliff there are still low fences of stacked rock known as “drive lines” that the natives used to steer the herd off the edge. Over 6,000 buffalo are guessed to have plummeted to their deaths. The bone pit at the bottom is 13 feet deep.

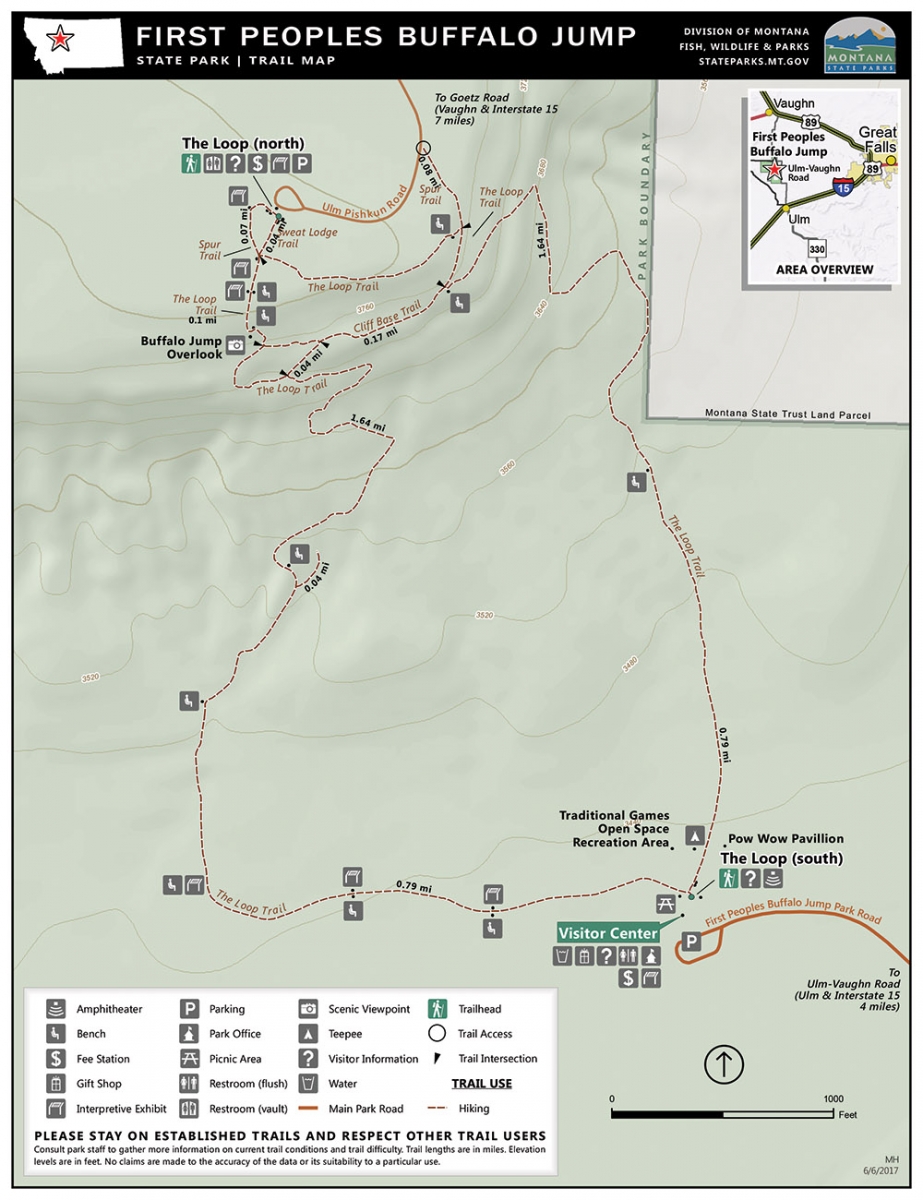

Walking the interpretive trails below and on top of the jump will take you back in history. Tipi rings lay where they did a thousand years ago, overlooking the magnificent Missouri River and glorious Square Butte. A visitor center at the bottom offers a storytelling circle, outdoor amphitheater, and arena for traditional games. Inside the building is a classroom, art gallery, and bookstore.

First Peoples is day-use only, but a good few hours is just right. Break up a weekend in the Breaks or a fishing trip on the Missouri. Hike the trails, bike the roads, and even bow hunt certain areas at certain times. Walk the cliff edge in a slow, deliberate manner, imaging what it was like when hundreds of animals roared off into space, taking their last steps without having any idea what was coming.

No matter the season, the deep blood kettle bears powerful history and nostalgic presence. Add it to the list.