The Headwaters Relay

A relay race unlike any other.

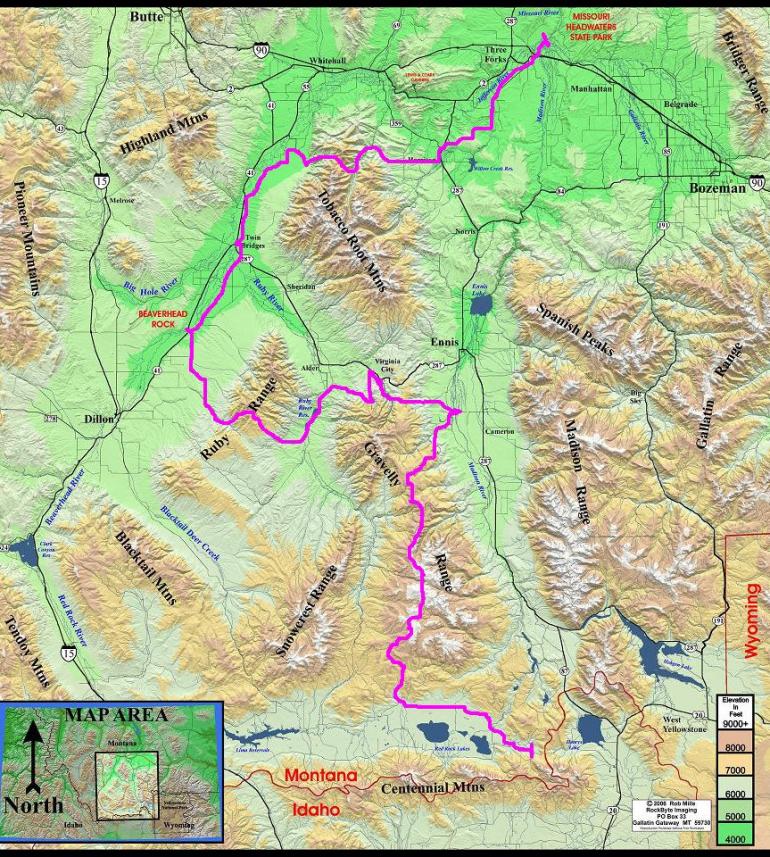

We’d done it. Our team ran all the way from Headwaters State Park near Three Forks to Hellroaring Creek in the Centennial Valley—235 miles through spectacular Southwest Montana country. It took three days of running as a rag-tag group of serious and not-so-serious runners, and now, we soaked our tired legs in the ice-cold water of this small, sparkling mountain creek, where the grueling “Headwaters Relay” ends. All the other teams dipped in as well, since a team cannot officially finish the Relay without each member immersing at least some body part in these baptismal waters. We’d raced hard each day, divvying up the 18 different legs among our six runners. The "mileage hounds" on our team ran the bulk of the route, while a few runners opted for the race minimum of five miles a day. I landed somewhere in the middle.

Not that every team genuinely "races" over the entire three days. Many runners are more recreational than competitive, lured by other attractions than winning. This relay offers the rare opportunity to travel leisurely—that is, on foot—through the less-visited territory of Southwest Montana: Axolotl Lakes; the entire Gravelly Range; the rural Jefferson Valley; the Ruby Range and River; the majestic Black Butte; and finally, the remote Centennial Valley. The route also takes runners through Virginia and Nevada City at the height of the tourist season, where onlookers on their summer vacations are a bit surprised by the sight of half-naked runners ripping through town on their way back up the Gravellys. It's not all pristine country either; on their way up (virtually straight up) the Ruby Range, runners witness one of the more remote mining operations in Montana.

And then there's the simple joy of working as a team over three days to achieve a common goal. Because there are no aid stations or course marshals along the way, runners have to support each other, with liquids, food, transportation, and most importantly, inspiration. When the going gets tough, especially on the last day, there's nothing like having your very own cheerleading squad appear at every turn. In this case the cliché works: the team is truly more than the sum of its parts. A fatigued runner can squeeze a lot more out of her body when her team supports her every step. On our third day, as we raced along the 9,000-foot spine of the Gravelly Range, we cheered on one of our team members as she held off a speedy high-school guy who was trying desperately to catch her the whole way. A recreational runner visiting from North Carolina, she was both elated and dumbfounded by her performance. Listening to our exuberant cheering, you'd think she’d just won the Boston Marathon.

Moreover, a certain camaraderie and mutual support evolves among teams in the relay who are presumably competing against each other. In 2003, with temps in the 90s and 100s, a spirited high school team from Missoula earned the name the "the super-soaker squad” as they showered runners from all teams with their Wal-Mart water guns. And as we relaxed around the campfire on the last night, downing burgers and beers with abandon—this time, no 5:30 am start to worry about—it certainly felt as if all the teams ran as one.

However, if it is intense competition you want, then there's no fiercer and more relentless racing than in a relay of this kind. Imagine racing three 10ks a day for three days, which is typical for a competitive runner on a smaller team. If you're fortunate, you can find yourself neck-and-neck with another team for three days. In 2002, on the first day, the top two teams were dead-even at the start of the last 3.2-mile leg, after more than 10 hours of running.

Ultimately, the Headwaters Relay exists as a kind of celebration of the precious waters of the otherwise arid landscape of Southwest Montana. It gets its name from the fact that runners travel from Three Forks, where the Missouri River proper begins, to Hellroaring Creek, which is the official source of the Missouri (that is, the farthest from the Atlantic Ocean of all the water that flows into the Atlantic). Of course Lewis and Clark believed they had discovered the true source some one hundred miles west of Hellroaring in the Lemhi range. But as the Brower expedition revealed in 1895, the Corps of Discovery should have kept following the Red Rock River into the Centennial Valley for the true headwaters.

In between the Missouri and Hellroaring Creek, the Relay fully exploits other waters for their therapeutic effects. Runners soak in the Beaverhead near Dillon at the end of the first day, and in the Madison at Varney Bridge at the end of the second. For scenic value, nothing beats the tiny Axoltl lakes nestled high in the Gravelly Range, directly across from the Madison Range’s towering Sphinx Mountain. But be prepared—some mighty large deer flies also enjoy the view.

In some respects the Headwaters Relay differs from the more well-known running relays in the country. For example, the largest and best known, "Hood to Coast", covers 180 miles continuously: the teams never stop but instead run through the night until they finish. Headwaters stops after about 80 miles each day, so teams can camp overnight in the same spot and then start together the next morning. Size is another difference. Whereas Hood to Coast, which is primarily a road race, can accommodate almost a thousand teams, Headwaters must limit its size to 25 teams due to the narrow two-track and dirt roads that comprise 95% of the route. In addition, Headwaters allows a team to choose their number of runners—as long as it is from five to ten—whereas other relays require a fixed number. To my knowledge, the only other three-day relay in the country is the Great Lakes Relay in Michigan, after which the Headwaters is modeled.

The 2022 Headwaters Relay was July 29-30. Each year, registration opens in late February. Call Don at 406-539-0368, or email [email protected].