Three Long Seconds

The human mind can process an astounding amount of information in a few short moments, especially when life and death hang in the balance.

My hunting partner Scott and I walked through the scattered subalpine fir, through granite outcroppings and intermittent ponds perched far above the distant river, visible occasionally through the trees like a foaming thread. The sun had gone down; dusk was coming.

Scott trailed me, carrying only binoculars. The evening before, we had stalked a bugling elk not far from where we now tiptoed through the forest. Last year it had been my turn to take the first shot; this season his, and I had watched him aim, fire, and bring down the bull. Now I was looking for my year’s meat.

We heard the step of a hoof in the evergreens ahead of us, then footfalls moving parallel to us, trying to circle downwind and get our scent. We dropped back through the trees, angling toward the faintest of hoofbeats more by instinct than sound, seeing, finally, the animal’s tan form cross a sliver of yellow meadow and head toward the dense timber that fell to the river.

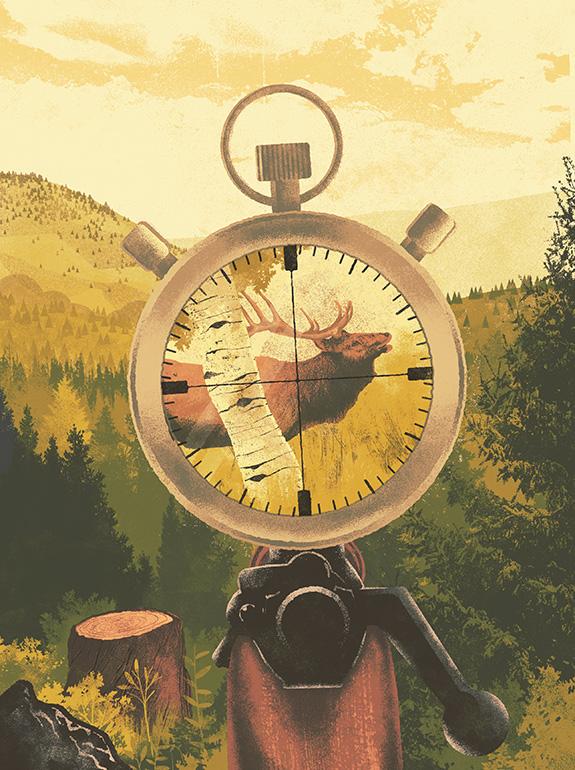

We sprinted in the same direction, and the bull, his curiosity dominating his caution, stopped suddenly between two trees, staring at us and exposing only his head, neck, and right forequarter. I raised the rifle and sighted at his neck from a little over 100 yards off, the shot perfectly clear down the alley between the trees.

Then the three long seconds began.

There is a difference between marksmanship at the target range and that in the field. Both take into consideration two elements: distance and wind. But shooting in the field adds four more: the upward or downward angle to the animal, the hunter’s ability to find a steady rest, how the animal is presenting itself, and adrenaline. I knew the distance to the elk from having shot thousands of rounds at the range and having watched elk in all sorts of places over the previous three decades. I was certain it was no more than 110 yards. The wind was little more than thermal drift directly behind me and of no consequence, the angle downhill barely discernible. However, my shooting position and the way the elk stood became immediate liabilities.

At 100 yards offhand, holding the rifle with only unsupported arms, I can keep almost all of my shots in a ten-inch square, plenty good enough to hit a broadside elk in its 18 x 18-inch vital area of heart, lung, and spine. If the bullet is a little off, it still kills the elk. I do even better offhand if I wrap my left arm in the sling, sometimes keeping all my bullets in a six-inch square at 100 yards. But, surprised by the elk, I had not put the sling around my biceps and it now dangled useless below the rifle.

And even if I could keep my shot in a six-inch square at 100 yards, that didn’t mean that, as the elk faced me, I would send a killing blow into the three-inch-wide spinal area of his neck. I hesitated, shifting the crosshairs to his right shoulder. He stared at me, antlers sweeping sideways and upward behind the trunks of the trees, his mane darker than their knobby boles, his eyes steady. Hitting his front shoulder would be no problem, but it’s not a shot I prefer or have ever taken, for it ruins too much meat, and fundamentally I hunt for food. Nor was I certain that the lightly constructed 165-grain bullet with which my rifle was loaded would make it through all that bone to a vital organ. I use this bullet instead of a stouter and heavier one because of its flat trajectory out to 300 yards. Without resighting my rifle during the season, I can hunt pronghorn, deer, and elk in varying terrain. The downside happens when an elk exposes only his front shoulder through the trees, which of course isn’t a problem if the hunter is patient and passes on the shot, a prudent trait easily practiced in southwestern Montana with its lengthy elk season. A patient and persistent hunter can look for, and almost always find, another elk—one who is willing to stand broadside in the open.

In the flash of a second, I’d factored all of these parameters of marksmanship, and now the murkier elements of this shot, and all it meant, welled into my mind. I wanted this elk now, because Scott had gotten an elk the previous evening, and there is always some little bit of desire to not exceed but match each other’s performance, even among the best and most laidback of friends. This is not competition but symbiosis. I wanted to kill this elk to complete our hunt, making it whole and perfect, as was the case two years ago when we both took elk and led the horses out of the mountains, surrounded by a dust cloud of comradeship and mutual accomplishment. I could already see the two great antlers on the backs of the Sorrel geldings.

As the second second vanished rapidly, my thoughts turned from friendship to neighbors and how my ego enjoyed being stroked annually by my larger community. Living in a place where people still praise those who consistently kill elk, I wanted to keep my winning streak going, for I had the reputation of knowing where elk were in the far backcountry, of hunting places too gnarly, steep, and tortured for most people, and of returning year after year after year with elk. I secretly liked the admiration of my neighbors and wanted to pull off, to be frank, one more coup, including this difficult shot between two trees.

And there was also the comfort consideration, to be sure. Having an elk in the freezer by early October left the rest of the fall to hunt grouse, pheasants, and ducks in a civil fashion: no 3:30-in-the-morning, sub-zero starts; no plodding through the woods on skis and snowshoes; no pulling out 100-pound quarters on a toboggan. The horses, after all, were waiting just over the rim.

Weighed against this easy recovery, however, was the meat itself. Last year’s rutting bull had been tough. Would this rutting bull provide another year of un-chewable steaks? Shouldn’t I wait for a cow or spike bull? And more to the point, what did I owe the animal himself? He was not a red-and-white sighting-in target, where a flyer on the edge of the paper would receive no more than my passing frown, signifying a blip in my concentration. He was staring eyes and wet nose. He was larynx and esophagus and vocal chords full of reedy bellow. He was scapula and humerus and vertebrae, a spinal cord carrying millions of bits of neural information, sight and sound and smell to his brain. Similarly, my brain was processing an equal amount of data, including that element that is always part of taking life if the human takes but a millisecond to think about it: integrity.

The last second floated by.

Beyond meat in the freezer and the bonds of friendship, and definitely beyond the invidious workings of my ego, there was what I owed the animal: a death as close to certain as certain can be. I lowered the rifle, thinking that perhaps if only I took the steadier kneeling position… The bull caught my movement and was gone in a flash.

Turning, I began to walk toward the rimrock, the next basin, and camp. Along the way, feeling, I think, most of what I had felt, Scott said from behind me, “Given the conditions, the light, you did the right thing.”

I heard him with only half my mind, for I was thinking of Lord Jim, Joseph Conrad’s star-crossed young seaman, who in a moment of indecision finds himself jumping into a lifeboat with a craven crew, looking up at his sinking ship and the hundreds of innocent, doomed souls he has abandoned. Saving themselves, the crew pulls away. But the ship doesn’t sink; the passengers are eventually rescued, and Jim is left with a stigma to bear the rest of his life.

I thought of him—of how close to pressing the trigger my finger had been, and of how, so often, we believe that we must do something, must act in some way to shore up the shaky mental and emotional persona quivering around the rifle. When, in fact, true boldness demands being quiet, examining our inner selves, waiting, and doing exactly nothing.

It isn’t merely the physical life at one end of the barrel that’s at stake, but the spiritual life at the other. And sometimes you get lucky, hesitating into the appearance of quietness, and the animal moves and saves your soul.

This article originally appeared in Bugle.