Why Do I Like Fishing?

The rain put the mosquitoes down. It came slowly at first, pushing up in the pines, spattering against the tarp. It always sounds as if it is raining harder than it really is when you are lying under a tarp or a tent. I kept my head down in my sleeping bag, not because of the rain that blew in sometimes from the side and onto my bed, but because of the bugs. They had been whining all night and I sweated hot in my sleeping bag and cursed them and cursed forgetting to bring a headnet and a tent instead of a nylon fly. I had wanted to go minimalist but the mosquitoes brought hard regret to that scenario.

It was too late, too far in, too much literal blood spilled to turn back. The mountains are named the Pioneers and I can only think of that pioneering spirit, somehow taking resolve in men and women long dead who didn’t have the luxury of bug dope, nylon tarps and down sleeping bags.

But the rain put the bugs down, especially when it came harder and with lightning that danced on the ridges above my little river valley, that flashed and struck and boomed and trembled the earth quicker than you can read these words. I hunkered down and listened to it coming hard, wind up loud, lightning dancing. I thought about my fly rod leaning up against a tree and remembered something about reading that lightning was attracted to graphite. The mosquitoes are an afterthought now. But the storm moves, rolls across the mountains and I hear it booming loud, then softer, then a distant flash and rumble down off over the valley where the lights of Dillon crease the very thin edge of the eastern sky.

Breakfast comes and the bugs with it, almost immediately. It is as if they are born right there in the rain-washed grass and for all I know, they are. I swat them frantically, then tell myself to calm down, superstitious that bugs are attracted to thrashing like sharks to wounded bait fish. I pour a pile of yellow garlic powder into my hashbrowns, thinking maybe that will work.

The stream is out beyond camp, behind the willows. Last night, I had time for a few casts, and caught a few thick, fat cutthroats in the bended water of the meanders. Enough to laugh a bit and enough to distract me for a few seconds from the blood fest going on around my head and on my arms and bare legs. I laid on the bug dope then, and am not out of the hot sweaty sleeping bag a minute before I slather on more. My more crunchy friends would chastise me for the chemical repellent and urge me toward citronella or something. But there is a frenzy going on and I coat on the DEET. Give me chemicals! I’ll take my chances.

The bugs drive me to the stream. In places, the deepest bends, I can get my bare legs down into the water to just above the knee. At least the bugs can’t get me underwater, so I slash through the willow, ignoring the itch of nettle on my calves, and submerge. The water feels good on old bites from last night.

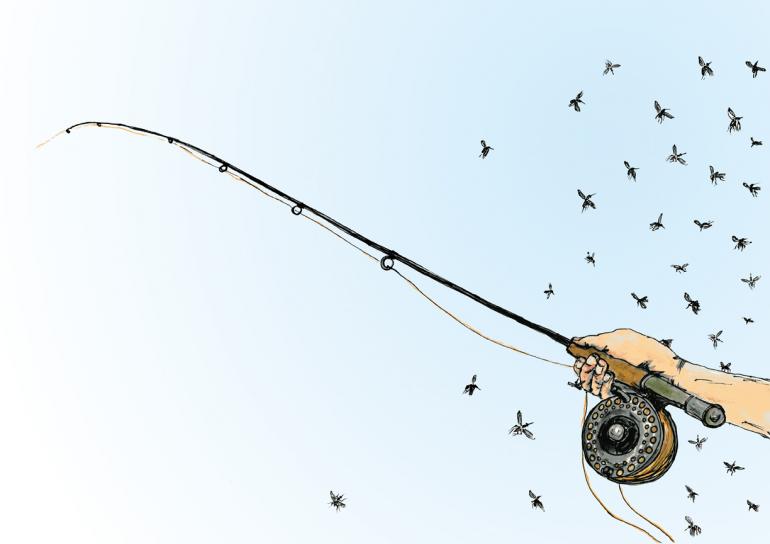

I am in a slick run that bends through willow. There are mink and elk tracks on the sandbar at the head of the pool, and debris—pine needles and old aspen leaves and gray-dead corpses of willow and alder—piled up above the water line. The water at the head of the pool forms an edge and I make a slow, easy cast and ease the fly onto the water. A fish rises quickly, a slashing splash, and I miss the hookset and the fly is behind me, trapped on a tall willow, wound around it and not coming off. I slap at mosquitoes and tell myself, for the thousandth time, to keep a calm demeanor, and reach high into the willow where my fly is pinned. It is out of my reach, so I pull down hard on the willow and the branch snaps out of my grasp, tightening suddenly on my line and snapping back and the tippet gives. There is the fly, up in the damned tree. I can see it. But the bugs are eating me alive, feasting on my white legs. I dive back in the water and the bugs come with me, whining like 10,000 tiny helicopters in my ears. I dig through my fly box and bugs coat the backs of my hands, impervious to a fresh coat of DEET. Or maybe I somehow washed it off.

I tie on another fly now. Swatting.

It is like this for an hour or more—the rhythm and beauty of fly fishing something so distant I think I may have read about it when I was a kid once. On this stream of fly-trapping willow and insect predators, it seems like a myth. Why do I like fishing?

I find a nice pool, make a cast and the fly wraps twice around the overhanging fingers of a willow at the head of the pool. I pull at the snag and the fly snaps back into my face and snags in my shirt collar. I spend what seems like ten minutes trying to unhook the fly, getting eaten alive. Now there are horse flies and those bastards hurt. The only good thing about them is I can feel them bite my flesh and they are slow carnivores and usually die with a hard slap before they can fly away with a chunk of my meat in their jaws. Ugly creatures with psychedelic tie-dye eyes and they squish satisfactorily to my yelp and slap dance. Sonofabitch! Slap!

Why do I like fishing?

The sun is up and hot—full now and the mosquitoes are down somewhat. The horse flies, though, take over this shift. That and the deer flies, triangular black bodies, quicker than the big flies, and just as painful. One of my hands is swelling slightly from bites, a minor allergic reaction I’ve gotten used to.

I work up the stream, casting and slapping and not much catching. Small cutts rise eagerly for my dry fly, but there is no joy in the day. Once, I slip on a submerged dead alder lying coppery and slick beneath the surface, and go down. I land face down, catching myself with my left, raising the rod high in my right, protecting it. At the last second I drop the rod so it won’t snap as I go down. I am wet to the chest, but it oddly feels good. Some of the bugs have bitten through my shirt and the wet cotton is a relief. I pull the rod out of the water, and wash the reel free from sand and grit, and blow on it and then wash it again. It is a while before the grating of sand on metal disappears when I turn the handle.

I make the beaver ponds, still awkward, not going right. It hasn’t gone right since I left the truck at the trailhead. Some trips are just like that. Not right. Stumbling. Stubborn. Going on.

I work up to the top of the pond and make a few casts that land okay. Land well, in fact, and I catch a few cutthroat now that are bigger. I move to the next pond where it pushes up against a sage-cloaked hillside and decide to climb. Maybe the bugs will be okay up there on the sagebrush and at least I can look down into the pond and see if there are any fish worth it.

In wet felt-bottom sandals, I slip on the grass, and go down again, thrusting out my left hand and drawing blood on sharp gravel. Why do I like fishing? I grab handfuls of sagebrush, whole stems of it, and climb higher, up to a small rock pile and I lean out over the pond and look down.

It lies out slick before me, this pond. Shallow at the dam and mud like wet dust loose at the base. Thick, bottomless muck. Deeper near the head, with channels for the dam-builders. A drowned willow mid-pond. I see a few fish, swimming lazily. Foot-long trout. None are rising. But at the head of the pool, I see a shape. I look for a long time before I realize I am looking at a tail. The tail of a really big trout. A trout of perhaps two feet. I watch him now and he rises slowly and takes a drowned ant off the surface, then slowly down. I see the white as his mouth opens, then closes, then he goes back to his soft finning in thick clear water. I feel an excitement rising, almost as if the little blood left in my body from the attack of the killer insects is coming back up in my arms and chest. I have ant patterns in my fly box.

This is why.

Tom Reed lives outside the town of Pony and is the author of Blue Lines, A Fishing Life, which is available online or at bookstores around Bozeman. For more information, visit tomreedbooks.com.