Shifting Gears

Fishing by motorcycle, from Bozeman to the Castle Mountains.

The formula for happiness in my world is simple: ride, fish, camp, repeat. I like to avoid the banalities of interstate travel, so I ride a so-called “adventure motorcycle”—a bike built to handle on-road touring and light off-road duty with equal aplomb. Similar to its rider, the bike’s not very comfortable on the interstate, which is fine for the trip my friend Brian and I have planned through the Castle Mountains. We’re not just “motorcycling”; we’re going on an exploratory camping trip that will involve fly fishing and riding motorcycles.

Brian arrives just after breakfast and, as usual, I’m putzing around the garage, fiddling with my bike, making fly selections, and trying to squeeze a backcountry espresso maker into my saddlebag. Finally, I’m packed and the single-cylinder in my bike is thumping. We begin our ride by immediately moving from pavement to dirt as we enter a county road system that will take us across the Bridgers and alongside 16-Mile Creek for the next 50 miles.

It’s a perfect summer day. We’re moving along the dirt and gravel through ranches and wandering cattle until a double-track takes us across a deserted field that connects with an impassable-when-wet county road. The road meanders through the uplands adjacent to the northern Bridgers and emerges at the semi-ghost town of Maudlow, where I pause at the bridge to look down at the pellucid waters of Sixteen Mile Creek. The fish are readily visible in places, and I’m eager to dismount, rig up, and head down to its banks. But our ride is just beginning, and the trout streams I plan on fishing are 100 miles further along.

By the time I look up, Brian has ridden ahead, struggling a bit on his slightly larger bike as he drops into the loamy sand at the bottom of a small swale. The dirt road is at once relaxing and exciting, depending on speed and how ambitiously one approaches the cattle guards. We motor along through spellbinding countryside, popping back onto pavement at the town of Ringling. The most recent census put the population here at 46 people.

We divert our course for a while to seek out a lesser-known portion of a widely known trout stream—an endeavor that has us riding down double-tracks and dusty, silt-filled county roads. There’s an effort underway to purchase a tract of land along this portion of the creek to create a public fishing access, so naturally we assume there must be noteworthy fishing around somewhere. Our search, however, is turning up nothing but a mud puddle of a “creek,” and I can’t bring myself to string up and cast a fly. Since these bikes get between 50 and 60 miles per gallon, I’m okay with the fail. The thrill of the quest is half the reason to go searching for lesser-known fly water aboard motorbikes in the first place.

Back on Hwy. 89, we ride north toward the Castle Mountains, just east of White Sulphur Springs. Turning onto Hwy. 294, the sound of Jimi Hendrix’s guitar reverberates throughout my helmet. He belts out “Castles Made of Sand” as the similarly named range comes into view. After leaning my bike through an array of Gibson-esque curves, the forest road that leads through the Castles from south to north appears on my left. I turn toward the ghost town of Lennep and park beside a bridge spanning an enticing rivulet with a reputation for good-sized browns. I rig up my rod.

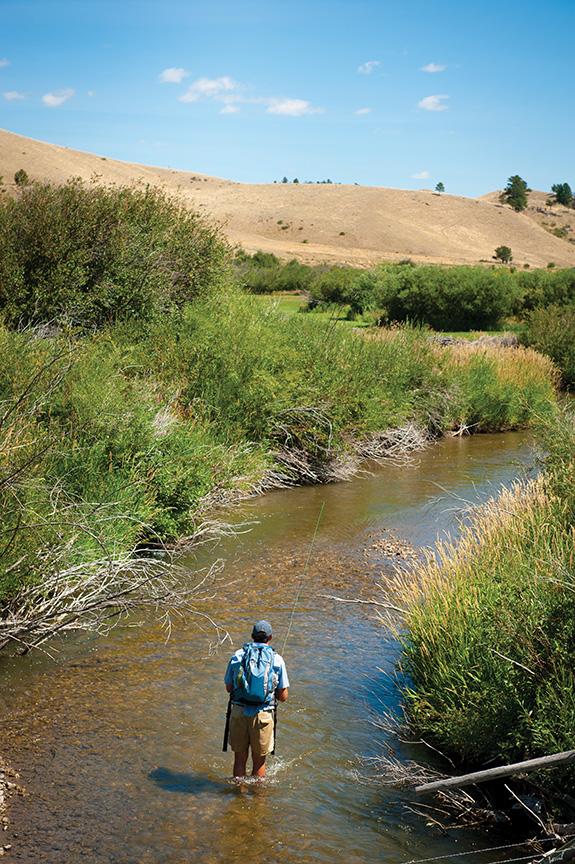

It’s a hot summer day in Montana, so wet clothing dries quickly—a good thing, as I often wade in motorcycle boots to repel snakebites in these prairie streams whose banks teem with rattlers.

After netting a few browns, Brian and I slip our bikes into gear and venture on to find a campsite before sundown. We ride through shady timber and cross a creek at the bottom of a deep canyon. Here, singletrack departs from the forest road and continues up a lush and protected creek bottom. We make camp and unburden our bikes of their saddlebags. Unweighted, we ride the bikes out of the canyon, which opens up into a high-mountain plateau. Panoramic views of the valleys below and the ranges that divide them are laid out before us. Thoreau would have liked it here, I think.

We spend the last hour of daylight exploring the upper reaches of the plateau, watching the sunset astride our bikes. In the lingering twilight, our stomachs tell us it’s time to eat. While Brian prepares the steaks, I get the campfire going. With pure wizardry, he prepares our ribeyes perfectly—no easy feat on a camp cooker. Car camping this is not, but we were able to pack some wine and a flask of whiskey, so after some conversation about tomorrow’s ride and a bit of philosophizing, sleep comes easily.

In the morning, it’s cold enough that a warming fire goes nicely with coffee and breakfast. We head back to the high plateau from the day before, enjoying idyllic weather: blue skies and a warming sun. It gets me thinking about our next stop, a small creek feeding the Musselshell River to the north of the Castles. By the time we reach it, the air will be hot, and that means active grasshoppers—and just-as-active trout. Gradually we descend from the high reaches of the Castles and pass through the “town” of Checkerboard. Small Montana towns like this one have a way of opening themselves up once you stop for a while, especially if you’re on a motorbike set up for camping and fishing. I wished we could spend a night here and meet some locals, but hopper-fishing awaits.

From Checkerboard, we hit pavement for the first time in over 20 miles and Brian rockets off down the canyon. The well-worn pavement feels pleasant and the canyon in front of us is shaded and inviting. I get Hendrix going again and feel an involuntary smile spread across my face as I lean the bike into the curves. Occasionally, I peek at the meandering creek below, where trout fin in their runs awaiting an errant grasshopper. I’m grateful for Montana’s generous stream-access law, but wary of its ambiguity. Many times I find myself parking beside a public bridge, wading upstream, and hoping the locals don’t burn my bike out of resentment. It hasn’t happened yet.

Prairie creeks have a way of looking radically different when one is knee-deep in them. A seemingly docile and easily fishable stream can turn into something formidable and wholly unpredictable. Simply trying to reach this creek from the bridge puts me awkwardly amid a stand of willows crisscrossed by irrigation ditches and barbed wire. I fumble around a crude diversion dam and make my way into the creek’s main stream, where a complete barbwire fence awaits. Attempting to duck underneath it, the wire snags my fishing vest. There I squat in the middle of the stream, rod in hand, hooked like a rainbow on a line.

“Okay, Brian. I give you permission to photograph this awkward moment in the life of a wayward fly fisherman!” But he’s kind, and the camera doesn’t begin firing until I tear my vest free and fish my way upstream. Eager to redeem myself, I do my best to fish well, hoping to raise a trout from the first run, but it’s not to be. I make my way to a bend, where the stream courses out of view, and Brian announces his departure back to Bozeman. A wave of the hand and he’s off.

Now, it’s only me and the creek. I need to get upstream, past thick willows and below the high-water mark. So, holding my rod high above my head, I begin a delicate toe step upstream. The deeper I get, the more buoyant I become, until I’m bounce-stepping. Wondering if I might soon be swimming, I bounce along for a few more hops until my feet, now firmly planted, take me to the shallower tail-out of the run above me.

Finally, I can fish. I cast a #10 Whit’s hopper along the undercut in the rocks. Nothing. No fish even come out for a look. Meditating on the situation, it occurs to me that the naturals I’ve seen are bigger. I tie on a hopper that barely fits into my fly box, a #4 Rainy’s grand hopper. With an upstream cast, I deliberately slap the fly on the water, let it drift, twitch it once, then watch as a brown trout approaching 18 inches slowly emerges from beneath the rocky undercut and slurps in the ridiculous foam imitation. He comes all the way to hand.

Satisfied, I string up and head downstream. The groin-deep water is easier to manage going with the current and I’m quickly back at my bike. It’s late afternoon and mid-summer hot by the time I’m suited up. The riding will feel good. Somewhere between here and home, it will cool off and I’ll have to stop and add a layer. By dark, the adventure will be over, the bike back in the garage, life back to normal. And tonight I’ll lay in bed, imagining the roads, the creeks, the trout, the throaty hum of the bike twisting through the canyon at dusk.