Cutthroat Sleighride

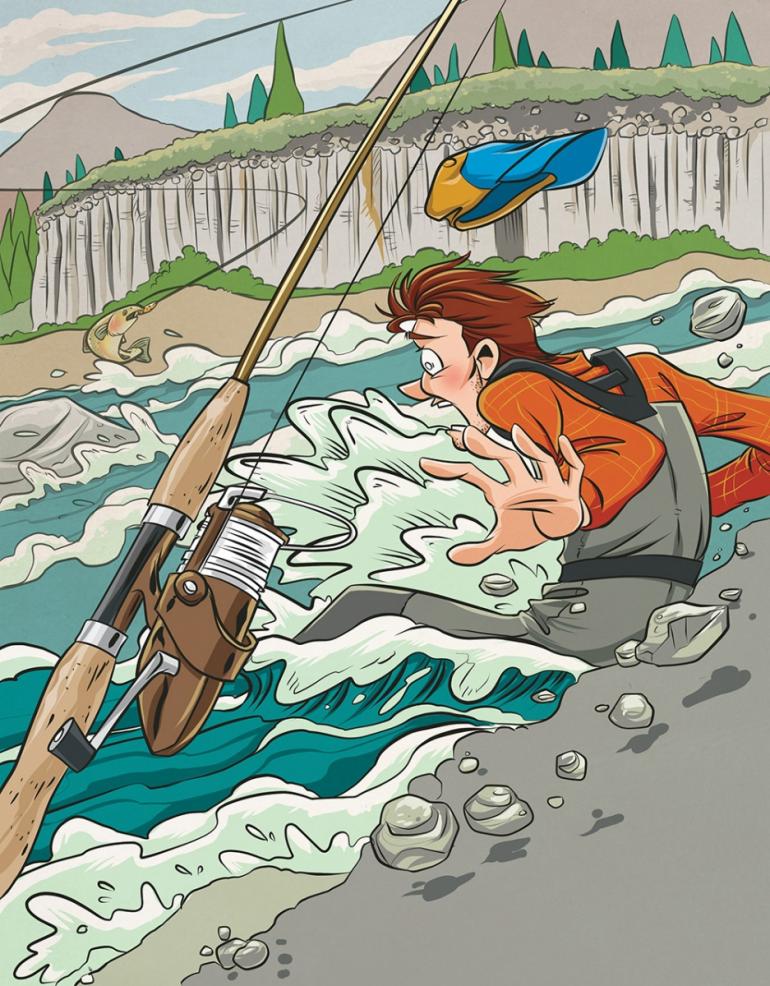

How a day of trout fishing turned upside down with a single cast.

A near-death experience always makes for an interesting day, who can deny it? However, that certainly wasn’t the sort of thrill I was chasing the morning I made my first-ever trek into the backcountry of Yellowstone Park. All I had in mind on that chilly Tuesday in May was a day of fishing for wild cutthroat on a remote stretch of the Yellowstone River in the northwestern corner of the Park. But on my maiden trip to Blacktail Canyon, Yellowstone had other plans for me—and before that memorable morning was over, I’d discover that fighting a big fish isn’t nearly as exciting as fighting for your life.

I was newly employed as a cook in the Mammoth Hot Springs Hotel kitchen that spring, and though I’d arrived as a trout-fishing neophyte, I figured since I’d be living in the Park all summer, I might as well give it a try. Fortunately, one of the waiters I worked with—a boisterous Hungarian exchange-student named Zoltan—was an avid angler, and when he volunteered to coach me, I hitched a ride to Livingston and outfitted myself with a three-piece pack rod and lightweight spinning reel. Once I was geared up, Zoltan and I spent our free mornings casting from the banks of the Gardner River, just down the hill from the hotel.

Zoltan had grown up fishing in the mountains of Slovakia, and he proved to be an excellent coach. He soon had me hooking small rainbows and browns with a Panther Martin teardrop lure, and whenever I’d reel in a fish during one of our practice sessions, Zoltan would pump his fist and shout in Hungarian: Szep munka! (Good job!). But the shallow waters of the Gardner River didn’t offer the big cutthroat the Park was famous for, so when Zoltan judged me ready for a tougher challenge, he proposed a trip into the backcountry to fish the Yellowstone River in Blacktail Canyon, where the boulder pools above Knowles Falls were said to harbor monster cutthroat. “Count me in,” I grinned. “Let’s go hook some lunkers.”

Dawn was breaking over Bunsen Peak when I stepped out of my dorm room on the morning of our trip. The air was crisp, the grass white with frost, and the sagging volleyball net on the dorm’s front lawn was rhinestoned with dewdrops that had frozen solid overnight—nature’s little reminders that I was now living 6,000 feet above sea level. To a lowlander from Long Island like myself, the raw spring weather of the Rockies had come as something of a shock; but I soon adjusted and after a few days, the chilly mornings at Mammoth seemed as normal as the rotten-egg smell drifting down from the sulphur-rich hot springs overlooking the hotel grounds. For a change, there were no elk grazing on the dorm’s lawn, so I didn’t have to watch my back as I hustled across the road to the employee dining room to meet Zoltan for breakfast. We’d agreed to rendezvous at 5:30 am, but he still hadn’t shown up by the time I finished eating, and I began to worry that he’d slept through his alarm. I ran over to his room and pounded on the door. When he finally opened it a crack, he peeked out at me with bloodshot eyes and moaned. “Sorry, Pete, I kind of overdid it at the pub last night.” I frowned and told him he was sorry, alright. But there was no point berating him further. He’d already put me half an hour behind schedule, and I wasn’t getting any closer to Blacktail Canyon standing around in his hallway.

The little Uinta ground squirrels the locals call “whistle pigs” dove for cover as I jogged across the lawn toward Grand Loop Rd. on the edge of town. The trail guide stashed in my daypack located the trailhead seven miles east of Mammoth. A short trip if I could hitch a ride with a passing tourist. Or a two-hour uphill hike if I had to make it on foot. I was hoping for the easier option, but there wasn’t much traffic, so rather than wait for a ride, I set off along the roadside, pausing to pivot and wag my thumb whenever the occasional eastbound car or RV passed me by. Everyone blew by me like I was invisible, and I wound up hiking nearly three miles—all the way to Undine Falls—before a patrol car eased to a stop in front of me. Approaching the car, I braced myself, expecting to be hassled for hitchhiking. To my surprise, though, the ranger simply waved me over and offered a lift.

“Where you headed, son?” he asked, as I shucked my pack and climbed in.

“Blacktail Canyon, to do some fishing,” I replied. “I’m cooking at Mammoth Hotel for the summer.”

“That’s what I thought,” he nodded. “I’ve seen you a few times at the Post Office in your cook’s whites. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have stopped. I’m not really supposed to pick up hitchhikers when I’m on patrol.”

“Well, I’m glad you recognized me,” I smiled. “I’ve been trying to catch a ride for the past hour.”

The cruiser’s dashboard clock showed 7:45 when Ranger Paul dropped me off in a gravel parking area just past the marshland of Blacktail Ponds—later than I’d planned, but if I hustled, I might still reach the river by 9:00. I thanked him for the ride, and as he was pulling away, he called out the window, “Don’t forget to sign the trail register.”

The trail register? What the hell’s he talking about? I wondered, as I shouldered my pack. Then I spotted a post-mounted wooden box at the back of the parking area. I walked over, lifted the hinged lid, and there it was: a clipboard with a sign-up sheet and a supply of stubby pencils like the ones they used to hand out with score-sheets in bowling alleys. Impatient to get on the trail, I hurriedly filled in the requested information. One of the questions on the sheet asked for the number of persons in my hiking party, and as I jotted down “1,” I felt a faint twinge of apprehension, remembering the Park Service safety pamphlet I’d been issued with my employee orientation packet, which cautioned against hiking solo in the Park’s backcountry. But like many a clueless greenhorn, I told myself I’d be just fine on my own.

The first section of Blacktail Deer Creek Trail led me over a steep, grassy hill dotted with clumps of fragrant sagebrush, and by the time I reached the crest, I was huffing and had to stop for a breather. But the hard part was behind me. From there on, it was downhill all the way to the river, three miles north. I gulped a few swigs of water and started the descent, jogging at an easy pace and keeping a cautious eye out for basking rattlesnakes on the winding trail ahead. Of course, rattlers weren’t my only concern. I’d heard enough about grizzlies to know that you shouldn’t go barreling around a blind curve without giving a shout first to announce your presence. And with the trail as winding as it was, I got plenty of practice shouting Hey, bear! Heeeeyy, bear! Which seemed to annoy the potbellied marmots whose burrow mounds lined both sides of the trail, but otherwise had no effect except bolstering my courage as I plunged ever deeper into unfamiliar territory.

Despite uneven footing on the rutted trail, I made good time for the first two miles. Then I came to the final stretch, which was precipitously steeper, dropping down in a dizzying series of switchbacks through a narrow, pine-choked gorge hemmed in by craggy basalt cliffs. No doubt this was the section that had earned the trail a rating of “difficult” in the guidebook, and when I reached it, I had no choice but to ease my stride or risk twisting an ankle. By that point, though, my burning legs welcomed the slower pace. I could only imagine how much worse they’d be burning when I had to climb back out on my way home. One thing seemed certain: it was going to take some fantastic fishing to make the pain I was in for on the return trip seem worthwhile.

The distant sound of rushing water grew steadily louder as I zig-zagged down to the canyon bottom, and when I rounded the final bend and reached the river, the Yellowstone’s roar was deafening. I’d expected it to be wilder than the Gardner, but this was scary wild, and I quickly realized I’d better take some time to scout it out before I started fishing. The steel suspension footbridge that crosses the river just downstream from Blacktail Deer Creek offered an ideal vantage point, so I walked out to the middle of the swaying span and spent a few minutes studying the boulder formations along the banks, looking for the most accessible pockets of slower water where the fish might be holding. I decided the south bank looked more promising, and started my fishing upstream from the bridge, in the outflow eddies at the mouth of Blacktail Deer Creek, where the water was less clouded by snowmelt than the Yellowstone’s main current. I got lucky right off the bat, hooking a feisty brook trout on the first cast of my black-and-yellow-spotted Panther Martin. After that, I was on a roll. I must have caught and released a dozen fish in less than 20 minutes. But except for a couple of two-pound cutthroat, all the rest were brookies, so I decided to move downstream in search of bigger fish.

About 50 yards downstream, I reached a backwash pool behind a half-submerged granite boulder that was bigger than a Humvee, and on my third cast into it, I hit the jackpot when my lure was slammed by a big cutthroat, which immediately made a run for the fast water midstream, taking drag all the while, until I thumbed the spool and got him turned around. But he wasn’t coming quietly. Before I knew it, he was breaking water and tail-walking, thrashing his thick head from side-to-side so hard, I felt sure he’d spit the hook. Beginner’s luck is the only way to explain how I managed to keep a taut line throughout his aerobatics, but when I eased him to the bank and got a close look at his size and the telltale red slashes beneath the jaw, I couldn’t help taking a cue from Zoltan. I whooped loud, Szep munka! It was easily a 20-inch cutthroat, and as I hefted it gently in the shallows to remove my hook, it felt like a five- or six-pound fish—a good job for sure.

My knees were shaking from the adrenaline rush as I picked my way down the bank to the next pool, and when I reached it I sat down on the smooth crown of another massive boulder to give my legs a rest. This pool looked much deeper than the previous one, so I pinched a couple of split shot on my line to make the lure drop farther and then made my first cast while I was still sitting down. Big mistake. Before I’d cranked three turns on the retrieve, I nailed a fish so heavy, it bowed my rod, and as I yanked back hard to set the hook, my balance shifted. Suddenly, my butt was sliding forward on the smooth rock and I could feel myself heading feet-first toward the water. Instinctively, I let go of my rod, which went flying into the river as I reached behind me and clawed at the rock in search of a handhold—nothing. A heartbeat later, down I went, flailing my arms as I hit the water—water so icy it tightened my chest and made me gasp. It was a good thing the daypack I was wearing was waterproof, or I’d never have been able to keep my head above water as the current swept me downstream, careening straight toward Knowles Falls and a 15-foot drop.

For the first few seconds, I was paralyzed with panic, but then some primitive survival instinct kicked in and warned me to keep my feet out in front of me, like a luge racer. At the speed I was traveling, a headfirst collision with a submerged rock would have likely knocked me unconscious. The boulders and pine trees along the bank were now whizzing by like a video on fast forward as I cupped my right hand and pushed at the water till my body began angling away from the main current and toward the riverbank. The bare branches of a deadfall tree loomed just ahead, and as I swept by, I grabbed on with my left hand and managed to swing myself into the safety of a backwash eddy. My hands were so numb; I could barely feel the rocks I grabbed as I hauled myself up onto solid ground. Looking back upstream toward the suspension bridge, I realized I was much further downriver than I thought. After only two or three minutes in the water, I was now more than half a mile downstream from where I’d hit the water—and four miles away from the nearest road back to civilization. My body was shivering violently, and I immediately realized my only hope of avoiding hypothermia was to make a run for it. So that’s exactly what I did.

As much as I’d been dreading the climb out of the canyon, I was just as grateful for the burning in my calves and thighs as I ran for my life up the dozens of switchbacks. It hurt, but it beat the hell out of freezing. And despite my soggy clothes, by the time I reached Blacktail Plateau, I was overheated and sweating nicely—and already looking forward to telling Zoltan about my Yellowstone version of the old New England whalers’ “Nantucket Sleigh Ride.”

Thirty years have passed since I took that wild ride, and I’ve heard a thousand stories from fishing buddies since then, but when it comes to tales of “the one that got away,” I always smile because I know I’ve got them beat. In my story, the one that got away was me.