River Time

On a high bank above the East Gallatin River, my father and I sat on the hood of my beat-up ’64 Pontiac Catalina, sharing a beer. The early-afternoon sunlight filtered through the trees, warming our upturned faces. After the last swig we hopped down and got our fishing gear together. I noticed Dad having trouble with his knot, and after his fifth failed attempt I reached over, took the line, and said, “here, let me show you a trick.”

“Thanks,” he said, looking at the water. “Which way are we going?”

“Upstream,” I answered. “The holes are a little bigger up there. There’ll be room for both of us to fish.” He nodded, following me down the bank and through the waist-deep water to a sandy bank on the far side. In a few minutes we were at the first hole.

We were fishing my favorite piece of water—a small, trout-filled river just ten minutes from town. Dad was visiting from California, and after the usual sightseeing routine he suggested we do some fishing. Considering our options, I decided this place was our best bet. It was beautiful country; the meandering East Gallatin was framed by huge alders and cottonwoods, and the thick, lush undergrowth of its banks was home to whitetail deer, red fox, and the occasional beaver. The fish were a little on the small side, but as reliable as they come.

Dad hadn’t been fishing in over a dozen years and I knew if I gave him a fly rod he’d only succeed in wrapping himself in a cocoon of fly line. So I dug out an old spinning outfit and picked up some nightcrawlers. He’d caught enough fish on spin gear in the old days to remember how to use it now.

In fact, it was he who first took me fishing. I was eight years old, and we’d just moved to Montana from L.A. The family had come here on a whim, selling the business and house and packing up after a two-week visit the previous summer. Dad was captivated by Montana—it was vast, alive, uncorrupted, and pregnant with the promise of adventure. The cold, clear rivers and majestic mountains touched a cord deep within him, and he responded the way young men do—by embracing it. Mom, still young and adventurous herself, put up little resistance.

Montana changed Dad. He became an outdoorsman almost overnight, buying truckloads of gear and taking the family rafting, hiking, and camping. He chopped firewood every weekend and told us stories of high outdoor adventure every night. He bought me a .22 and taught me how to shoot it. He showed me how to make a lean-to and how to sharpen a knife. And he took me fishing.

Dad had grown up fishing the Pacific Ocean with his father, trolling for barracuda off the coast of L.A., and he seemed to believe that he’d be failing me somehow if he didn’t teach me how to fish. On Saturday mornings we’d grab the rods and some worms and head for the river. We’d sit on the bank and laugh as I snagged my pants or Dad’s hat while trying to cast my hook and golf-ball-sized bobber into the river. We’d doze off under the afternoon sun, stirring only for the occasional long and lazy stretch before drifting off again. Even in my dreams I stayed on the river, catching ten-pound trout and swimming under giant beaver dams. I’d awake to see Dad fishing again, and I would silently thank him for bringing me to this strange and wonderful world where dreams and reality flowed together in one continuous consciousness.

The years were hard on Dad. Like so many before her—and since—Mom couldn’t stand the cold, the isolation, and the slow pace of life. Though it seemed to give us freedom, the wide-open space made her feel small and alone. She was city-folk at heart, and she needed the security of people and buildings surrounding her. Dad loved her very much, and knew that her happiness was imperative to the well-being of the family. So back we went to L.A.

But things weren’t like before. With the business gone, Dad and Mom had to start all over. The next ten years were spent fighting a recession and trying to provide for a family of six. By the time things turned around, Dad was a different man. Though there were lakes nearby, he never joined me as I patrolled their banks, casting top-water plugs for bass as the sun sank below the dry California hills. He never came along on weekend trips to the Sierra Nevada Mountains, where I hiked to high alpine lakes in search of sleek, speckled golden trout. Those primal voices within him had been snuffed out by the blare of car horns and the incessant buzz of urban life. The city had taken something from him, something that would never return.

The fire in me never died, though, and after high-school graduation I packed my bags and drove north. I got an apartment in Bozeman, enrolled at MSU, and found a part-time job. And I fished. After re-visiting our old haunts, I went on to explore every inch of the rivers around Bozeman. I found superb stretches of water from Big Sky to Big Timber, pulling out big browns, fat rainbows, and hundreds of smaller, feistier trout. I saw deer, foxes, hawks, bald eagles, snakes, mink, porcupines, and even a fisher or two. And I waited for the day that I could show Dad these new sights and sounds, to share with him the innumerable wonders I’d discovered since those lazy summer days so long ago.

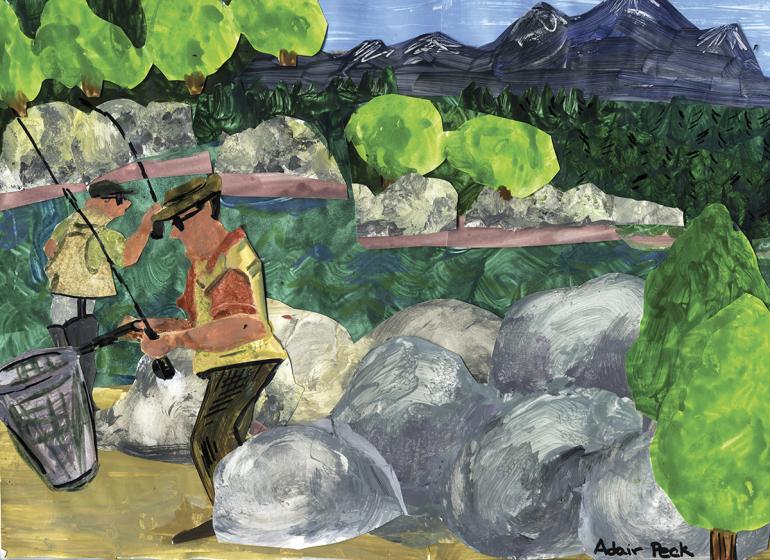

So here we were, together on the river again, after 15 years. Dad was rusty, so I explained quickly how to drift the worm, bouncing it along the bottom and waiting for a distinct tap before setting the hook. He nodded, gripped the rod firmly, and began a series of clumsy but workable casts. I caught a few fish as we worked our way up the bank, and Dad smiled approvingly at each one. After a few minutes I walked upstream and around a bend to the next deep run.

I fished slowly, waiting for him to catch up. When he hadn’t shown after half an hour, I walked back downstream. He was sitting in the grass under a tree, looking at the mountains. I realized then that my father hadn’t really wanted to fish. He understood what I hadn’t—that when life takes something from a man, it can’t always be taken back. Sometimes the years are just too many, the changes too vast to overcome. When the past can’t be restored, one must learn to live on memories.

Dad had been nursing these memories for 15 years. Stuck in traffic, inhaling smog, listening to radio reports of drug busts and drive-by shootings, Dad closed his eyes and drifted through time. He sat on a grassy bank with a young boy, looking at the gentle, winding river in front of them. He ruffled the boy’s hair and watched him cast his line into the water. He leaned back into the soft earth and smiled.

Seeing him under the tree, I knew that he didn’t need to fish anymore. Just being here was enough. I walked over and sat down beside him. Together we watched the water flow in its rhythmic, unchanging course. We listened to the chatter of the robins and to the steady hum of the cicadas. We gazed at the cloudless sky, the towering trees, and the long spine of the Bridgers looming in the distance. And we remembered.