Hooking Up with Bud Lilly

I met Bud Lilly in the fall of 1976, during a month-long camping trip to Yellowstone Park. I was a graduate student on fishing sabbatical, and when I entered the door of Bud Lilly's Trout Shop it wasn't to buy anything, but simply to pay homage at a Mecca of Western fly-fishing.

The old schoolteacher in Lilly must have seen in me a willingness to learn, for he introduced himself—I was too shy to have spoken with him otherwise—and when he heard I was camped at Madison Junction he explained to me in exact terms how, when, and where to cast a fly for the fish I had traveled more than 2,500 miles to catch. What I recall most about that tall, soft-spoken gentleman were his eyes. It was the eyes that smiled first and made you feel welcome, and when I walked down to the river the following dawn I could still hear the quiet authority of his voice. With the spirit of his hand guiding mine on the rod grip, I caught more large trout in the next few days than I had caught in nearly 20 years fishing in Midwest waters.

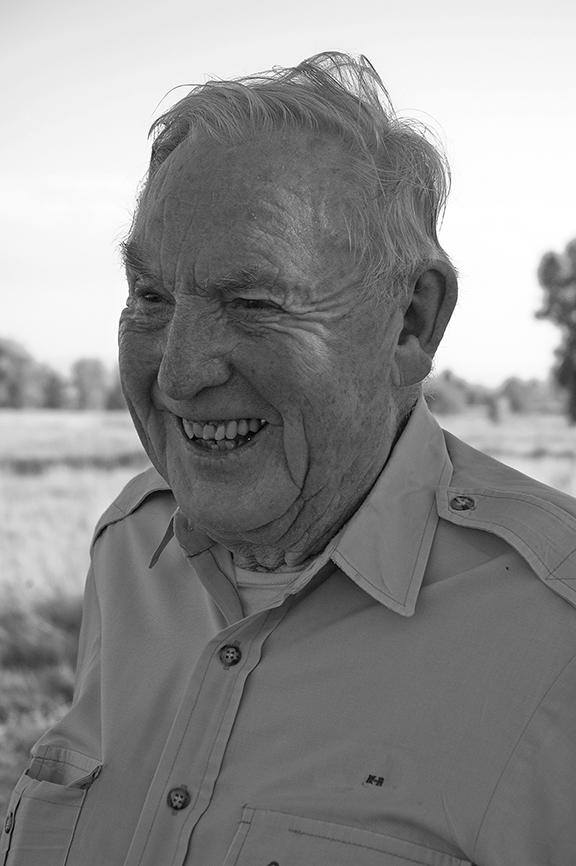

The man I drive to meet this January at "Bud Lilly's Anglers' Retreat" in Three Forks—a century-old, two-story, white clapboard home—seems little changed, despite his having undergone heart surgery to install a synchronization device less than a week before. At age 84, Bud Lilly's hair isn't as red as I remember, but it is still sandy and there are the kind eyes to greet you, the stately grace of manner.

Lilly's wife, Esther, who herself is a former executive of national Trout Unlimited and Federation of Fly Fishers, recommends a tour of the rooms upstairs, particularly the room she calls Bud's "shrine." It isn't a big room, but the south-facing windows gather the winter sun illuminating the mementos of a long life and career. Hanging on a peg is the Navy uniform Lilly wore as a young ensign during World War II and a framed portrait of the young man inscribed with his given name, "Walen F. Lilly, Jr."

Hanging from the west wall are the signature straw cowboy hats with the double crease by which thousands of anglers recognize Bud Lilly, each hat cracked, battered and sweat-stained from a thousand suns.

There is a letter from President Jimmy Carter, thanking Lilly for a gift of hand-tied flies, a collage of photos taken during a camping trip Lilly took on the Lewis River with the British ambassador. Here and there are signed photos from the luminaries he has shepherded on Western waters, men such as Tom Brokaw and Charles Kuralt. A tribute to three fly-fishing legends—George Grant, Bud Lilly, and Dan Bailey—adorns the north wall. Then there are the awards—The American Museum of Fly Fishing Heritage Award, Montana Ambassador of the Year Award, Legends of the Headwaters Award. There is a photo of a record 29-pound brown trout from Wade Lake that was displayed at Bud Lilly's Trout Shop in 1966. The big brown is the only photo of a dead fish, which isn't surprising. Bud Lilly pioneered catch and release in Western waters, creating the first catch-and-release fishing club in 1961.

If you didn't know Bud Lilly, it would be easy to think that the sum of the man's life was contained in that room. But he isn't about to dwell upon the past. His fame as a fishing shop operator and outfitter, which made his name synonymous with Western fly-fishing as far back as the 1950s, has simply been the springboard for a second act in conservation. The environmental historian Paul Schullery has called Lilly the "trout's best friend," but it can be argued that he is also the trout fisherman's best friend.

Among Lilly's latest projects is a cooperative effort with the Montana governor's office, Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to broaden the concept of river access and expand and maintain access sites for anglers.

"The river systems are the blood of our existence," he says. "But with more privatization, access is being squeezed down. These are national rivers. We all own them. As I look down the pike, I think it will be more vital than ever before to respect our rivers and maintain them in the highest regard, and to create equal access for everyone."

A Montana State University graduate who was awarded an MSU honorary doctorate in 2001, Lilly is the guiding force and chair of the Trout and Salmonid Collection in MSU's Renne Library, which includes some 11,000 volumes on trout research and fishing, the largest such collection in the country.

Another project dear to his heart is the Wounded Warriors and Quiet Waters Foundation, which he helped found in 2007. The project brings disabled war veterans, some gravely injured, from hospitals around the country to Montana where volunteers introduce them to fly-fishing and the healing power of moving water.

In addition to these projects, Lilly works with the Montana Land Reliance, the Whirling Disease Foundation, the Montana Trout Foundation, and is the director of Montana River Action, which works toward maintaining critical flow levels in trout streams threatened by dewatering. He is a past national director of Trout Unlimited, the Federation of Fly Fisherman, and the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

Lilly laughs when he says that his involvement with trout fishing and conservation began when he was born. A descendant of pioneers—his great-great-great grandmother, Mary "Granny" Yates, came to Virginia City during the 1860s gold rush—he grew up in Manhattan. His father, the local barber, introduced him to bait and fly fishing on the headwater rivers of the Missouri.

He distinctly recalls the first trout he caught, fishing in a diversion ditch a few miles outside town. His aunt Elizabeth recorded the momentous event in her journal.

"I was with Buddy when he caught his first fish," she wrote. "He jumped up and down and said, 'Goddamn! Goddamn!'"

Upon this blasphemy a passion was born.

The upside were trout dinners, enough not only for Lilly's family but for many others, for his father insisted that every fish be eaten, and many days Lilly caught 50 brook trout on grasshoppers.

"In those days, we didn't realize the value of a live trout or the value of a spawning tributary," he recalls.

Early leanings toward conservation that were encouraged by his father were put on hold during the 1940s. Lilly was 16 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. A fine high-school athlete, he'd harbored vague dreams of a pro baseball career and even came to the plate against legendary pitcher Satchel Paige, who was barnstorming around the country with Negro league players during the war. Lilly got a hit off Paige, but was promptly thrown out at second when trying to steal. His baseball dreams were dashed just as abruptly. By the time a letter arrived inviting him to join the Cincinnati Reds farm team in Salt Lake City on July 1, 1943, he already had taken a test offered by Navy representatives who came to Montana looking for officer material.

"I figured if nothing else, (the test) was a good way of getting out of school for two hours," he remembers. A few weeks later, he was in Annapolis' accelerated officer training program.

By June of 1945, Lilly was at sea. He spent most of the war in the Pacific on the USS General RN Blatchford, a troop transport ship that ferried 3,000 soldiers. It was aboard the ship that the 19-year-old ensign was shot when a kamikaze pilot sprayed the crew with its machine guns. Lilly's right pectoral muscle was peeled off by the gunfire. He was stitched up and back on the bridge the next day.

Lilly came home in July 1946. His father's greeting was to the point. "You know," he said, "the salmon flies are on the Madison River."

Lilly smiles. "I took off my uniform, found some old clothes, and went right back to fishing."

Lilly attended MSU on the GI Bill, graduating in 1948 with a bachelor's degree in Applied Science. He later earned a master's of education and for 20 years served as a high-school teacher in Roundup, Deer Lodge and in Bozeman, where he taught an accelerated science classes for advanced students.

"Like a fool," he remembers, "I thought I could live off a teacher's salary." When he couldn't, he and a friend started a summer car wash business in West Yellowstone. When Wally Eagle offered to sell him space for a tackle shop in his store near the entrance of Yellowstone Park, Lilly asked a friend for advice.

His friend said, "If you want to starve, buy it."

That was 1952, and the rest is fly-fishing history. Except for one major hiccup—the 1959 earthquakes ruined fishing for two years—Bud Lilly's Trout Shop was successful. It was a family operation, with Lilly's sons Mike and Greg doing the guiding, as well as his daughter, Annette, who was Montana's first licensed female fishing guide. His late wife, Pat, operated the art and clothing section of the store.

Lilly attributes his growing awareness that a trout could have value beyond its jumping ability and the succulence of its flesh to the customers who came through the door.

While Lilly recalled that he had regularly filled a creel "large enough to hold alligators," fishing luminaries including Al McClane, Ed Zern and Ted Trueblood brought a more enlightened set of ethics into the store. They had witnessed the decline of fisheries in the East. But it was Art Neumann, then executive director of Trout Unlimited, and others in that organization, who had the greatest influence.

Along with Pat Sample of Billings and Livingston tackle shop owner Dan Bailey, Lilly founded Montana Trout Unlimited.

"Dan had the knowledge, Pat had the money, and I had the willingness," he recalls.

One of their first projects was to oppose the Allen Spur Dam proposed by the Bureau of Reclamation, which would have guillotined the Yellowstone River south of Livingston. With a wild trout program, catch and release, special regulations for sensitive waters, adequate water flows to ensure spawning, the challenge to save Western trout rivers was engaged.

"Clean air, clean water equals good fishing," Lilly says.

As I rise to leave, I remind Lilly about meeting him during my first fishing trip to the West. At the time, I had thought that the part he played in my success was limited to advice; I hadn't realized that the trout in the rivers were largely thanks to him, as well.

He can't remember the brief meeting, which is understandable. But he remembers the places he told me to go, and soon we are poring over a hand-drawn map.

"Yes," he says, pointing his finger at a spot on the map "that's the first place I'd make a cast." And, "It's all in the angle of the presentation."

And for a few minutes he seems like a kid again, the buoyant enthusiasm dancing in the kind eyes that I remember so well.

As he once said himself of the wonder of trout fishing, "Goddamn! Goddamn!"

Photos courtesy Steve Hunts.