Challenge Accepted

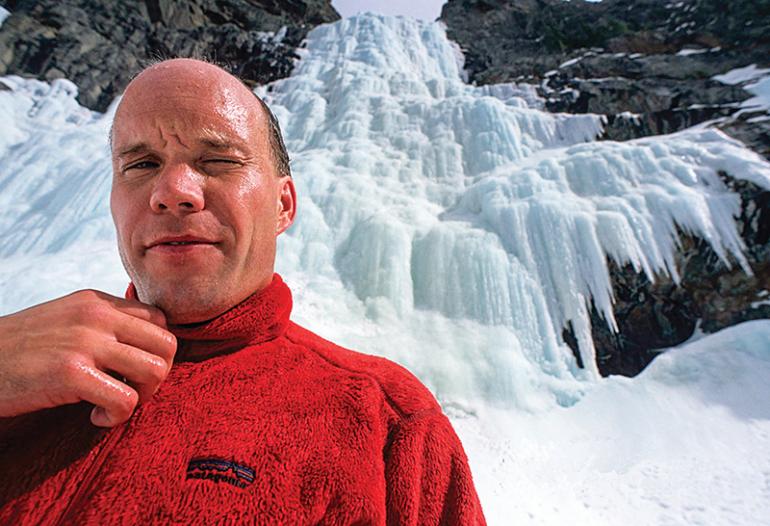

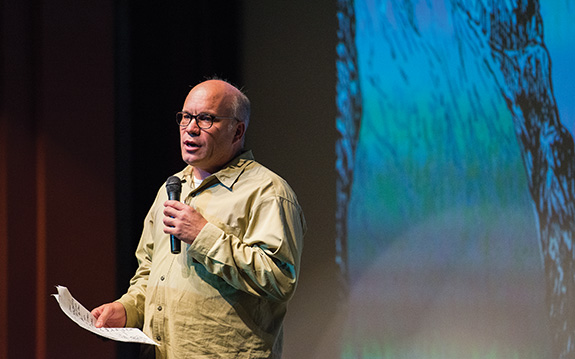

An interview with Joe Josephson.

In 2006, Joe Josephson was an avid ice climber, pioneering routes in Hyalite Canyon. By 2018, he was tackling some of the most complex land-management issues facing southwest Montana. How did he make the transition from recreation to conservation, and what challenges does he foresee within the movement? For part three of our four-part series profiling local advocates, we asked JoJo these questions and more.

O/B: What was your worst winter day in the mountains of southwest Montana?

JJ: Without question, the day in December 2009 when one of my best friends, Guy Lacelle, was killed in an avalanche in upper Hyalite. I was actually climbing on the other side of the canyon that day and heard the avalanche that swept him away. Maybe an hour later I was found and told that Guy was dead.

O/B: What was your best?

JJ: A below-zero day in January 2008, before the road was plowed, local avalanche forecaster and Hyalite pioneer Doug Chabot and I made our way to Cleopatra’s Needle, perhaps the most classic route in all of Hyalite near the familiar Twin Falls. We were the only ones around and it was a one of those magical winter days and for me, my first decent lead after not climbing for over two years thanks to a shoulder injury.

O/B: At what point did you realize you’d spend your life in wild places?

JJ: I was born a month early in June and like to say I came out early to not miss any of summer. My life revolved around the Beartooth Mountains since I could walk. So I don’t think there was any point of realization. It’s just part of me.

O/B: Why Hyalite?

JJ: There are loads of places with bigger routes and more routes and I’ve been to most of them across North America. But Hyalite holds that unique combination of being a backyard crag but still maintaining a feeling of wildness and mystery. No other ice-climbing destination in North America is so close to a town like Bozeman, nor is there any area with such a big diversity of routes that are all accessed from one parking lot (Grotto Falls). Don’t underestimate what that does to the vibe of the canyon and the community of climbers. It’s great.

O/B: Why ice climbing?

JJ: Growing up, the only climbers that I knew existed where Reinhold Messner and John Roskelley, as they were the ones you’d read about in mainstream magazines like National Geographic or Outside. So I didn’t know any climbers but wanted to be one. When I transferred to the University of Calgary in 1987, I had no idea the Canadian Rockies were the Mecca for the sport nor that I’d be at the forefront of a revolution in the sport. All I wanted to do was buy some used gear and climb waterfalls as the means to gain skills for bigger alpine climbs.

O/B: Who are some of your outdoor heroes and why?

JJ: I learned long ago that everyone is human so even the best or most famous have their issues. Many people have come and gone in my life that have and continue to inspire me but perhaps the only “hero” I ever had was Blaze DiLulio, a backcountry ranger in the Beartooths when I was growing up. He single-handedly brought many trashed areas back to life and educated a generation and beyond. He was a true legend.

O/B: Walk us through your transition from climber to advocate to conservationist. Was there a Eureka moment? Or did things progress slowly?

JJ: It was really the fight to keep the Hyalite road open during the Gallatin Travel Planning, 2003 through 2007. Bill Dockins and I along with rest of the Southwest Montana Climber’s Coalition were able to keep the Forest Service from closing the road at the bottom. At first, all we wanted was to keep it open until it snowed shut, giving us a 6- to 8-week ice-climbing season. At the time, we never dreamed that we’d end up with the road being plowed, creating an almost six-month season.

It was a huge lift and fraught with aggravation, but I clearly recall looking back at how much I enjoyed it. Of course, winning helps. Also, I was un- and under-employed during that time so I started applying for conservation jobs largely out of necessity.

O/B: You’ve had several conservation successes in the last few years. Tell us about a failure and what you learned from it.

JJ: Success is only measured using the yardstick you have in that moment. You win or lose games based on set rules. In life and conservation, the goal posts are constantly changing, sometimes by your own doing and often by forces outside of your control. Climate change, growth, technology, and commodity prices are just a few factors in constant flux, so the only real failure in conservation is to think that you are finished.

I learned in climbing that most of my epic “failures” have been a result of personal choices punctuated by a smattering of luck—some good, some bad. Either learn to make different choices and accept that conditions change or recalibrate the target.

O/B: What are the challenges facing the local and regional outdoor community? What are the opportunities?

JJ: For every mile or acre we protect today, it makes the next one tomorrow even harder. And this is particularly acute in an area like southwest Montana where there is already a wide variety and large amount of conservation designations in place. Hanging onto the way we worked, lived, or played 30 years ago, ten years ago, or even last year may not be valid for the future. If our attitudes and approaches don’t continue to evolve, we are little more than dinosaurs walking toward the tar pit.

O/B: Can recreation be used for conservation? Is it the only path forward for protecting wild places?

JJ: I used to believe that recreation made people fall in love with a place and that would motivate them to protect it. That may have been true before social media, but any more it seems loving something only motivates more consumption. The recreation-plus-conservation equation is complicated and full of challenging variables including inclusion and diversity in industries, outdoor spaces, and sports dominated by white colonialism. To consider recreation the only path forward is naïve and simplistic. Most of us are unwilling to admit to or face our own complicity in excluding others and our impacts on places that matter.

O/B: What role does private land, and ranching in particular, play in the future of conservation, recreation, and open space?

JJ: Ranching and private-land interests have always been a critical part of stewardship and conservation. Seeing them separate and the divide that has been created between “environmentalists” and property-rights advocates is unfortunate. As is the absurd notion of “fifth-generation Montanan,” as if they have more rights than a new resident. If I learned anything growing up in Big Timber, it might be that if I sat down with someone, anyone long enough and really listened, we’d usually discover we have more in common than not. Partnerships are only as effective as their mutual understanding of shared goals and common ground.

O/B: How can people effectively impart the importance of stewardship, without coming across as self-righteous jerks or the self-assigned police of public lands?

JJ: A jerk is a jerk. By definition, jerks are not interested in change and will always blame others. Eliminate them from your life. Focus on meaningful friends and family and communities and give back to a greater good when you can and in a way that is meaningful to you.

O/B: What are the ways we can make an impact every day? Voting? Letter writing? Other?

JJ: This is where I impart some hard-earned wisdom that should be on a bumper sticker, but at the end of the day if everyone did one thing, it would be to vote. Making daily change or taking time for action takes hard commitment and it’s all too easy to let that challenge be self-defeating and get in the way of the work. It happens to me all the time. Don’t beat yourself up over not doing enough today. Just strive to do better tomorrow. And vote.