Extreme Makeover: Fatbike Edition

How one Bozemaniac stepped outside his comfort zone and found more.

At 2am, I bundled up, loaded up, and followed fellow racer Martijn Boonman out of the minimal warmth of the Rainey Pass cabin into minus-40 temps and 50-mph winds. Heads down, step by painstaking step, we pushed our fatbikes through the deep snow, fighting the wind, hoping we were actually on a trail that would lead us over Ptarmigan Pass, through Hell’s Gate and on to the next checkpoint some 70 miles away.

After two hours, the winds eased. Martijn climbed onto his bike and pulled away from me. Shaken from my trance, I followed suit and pedaled to the sound of crunching snow. Wolf tracks littered the trail as the sky began to glow; the Northern Lights danced off the mountains, sending beams of green, yellow, and orange across the valley ahead. I started my iPod and AC/DC’s "Back in Black" filled my head. It was so cold that I could barely move my mouth, but I was smiling.

This—the snow, the cold, the pain, the constant threat to life and limb, ahead and all around me—this is what I’d come here for. And right now, there was no place on Earth I’d rather be.

Back in the Saddle

Seven months earlier, sweating in 95-degree heat in the Butte 100 mountain-bike race, I crossed the finish line feeling fit and ambitious—and that I needed something more, something further outside my comfort zone. A grander challenge was in order: one that would push me not only physically, but mentally and spiritually as well. It was time to sign up for the Iditarod Trail Invitational (ITI), a 350-mile race across the Alaska Range in February and a true test of endurance and willpower.

The ITI is a human-powered—foot, skis, or bike—self-supported race that follows the Iditarod dogsled trail from Anchorage to Nome. The brutal winter conditions, unforgiving landscape, and complete isolation force participants to rely on their preparation, stamina, and mental toughness. It’s common to wander off-course at night in avalanche-prone territory on wind-obliterated trails. Or you might fall into slushy overflow on lakes fractured by the extreme cold. Mistakes can be fatal.

Soaking in the morning sun at -40 degrees, Ptarmigan Pass.

Soaking in the morning sun at -40 degrees, Ptarmigan Pass.

But there’s a clarity that can’t be found anywhere else. You simply have to survive, which, it turns out, is simple: you do what it takes to move forward or you don’t make it. Such is the essence of the ITI: uncertainty, gut-wrenching fear, and the opportunity to face up—to face yourself clearly and honestly and find out what you’re made of.

I entered the ITI in 2001, 2004, and 2006 on a skinny-tire bike. I went into it the first time young, strong, confident, even a bit cocky, only to learn that the real strengths I would need were buried inside me, beneath all the bravado. I pushed my bike 200 miles that first year up and over the Alaska Range, finishing with a smile on my face. The next two years, the ITI got the best of me.

Extremely Comfortable

But why do it at all? Why subject oneself to suffer-fests that have no real bearing on modern life? These are the questions many a Montana outdoor athlete has had to face. From the Ridge Run to the Little Couloir, the Devil’s Backbone to the Kitchen Sink, Montana has no shortage of outdoor feats that test both strength and endurance, and require us to “screw our courage to the sticking place,” as Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth put it. They’re all demanding, challenging, and injury-inducing—and in some cases, deadly—but at some point, even these can become routine.

In the early 2000s, I was in my 30s, had raced mountain bikes professionally for years, and participated in expedition-style adventure races around the world. Racing, and the training it demanded, was an essential part of my existence. So, like many others before me, I moved to Bozeman to take advantage of Montana as a training playground for boundary-pushing challenges. These events filled an insatiable void, and training was a part of my everyday life. I grew stronger, pushed myself harder, and expanded my boundaries. Life was a bota bag of adrenaline-infused nectar, and I drank deep.

But like everyone, as youth gave way to middle age, I got distracted and consumed by an unrelenting barrage of commitments and responsibilities. My business had blossomed, growing to 30 employees. I was busy and that became my excuse for not pushing myself athletically, not taking risks like I used to. While I still raced in demanding local events like the Butte 100 and the Old Gabe, after seven or eight years, familiarity rendered even these races normal and predictable. At some point we have to ask ourselves if we are truly stepping out, facing our fears and insecurities, testing our strengths, taking a path that will lead to self-discovery and growth; or if we’re just chilling in the comfort zone.

Fact is, life stops in the “comfort zone.” Even the word “zone” suggests boundaries, separation, confinement. This is where ruts are dug and we bury ourselves in the excuses of why we cannot climb out and continue moving forward on the journey of life—be it work, family, or just plain fear. It is relative and we are all at different levels in terms of what drives us, challenges us, or gives us that inner uneasy feeling when we are about to step off into the unknown. But one thing we all have in common is this: if we don’t step off, we are not living, not growing.

250 miles in, 170 miles to go.

250 miles in, 170 miles to go.

For me, staying in this comfort zone had caused a gradual deterioration of my fighting spirit. I lost the discipline to train and push myself to a level where bigger challenges and races were obtainable. I began to see this as a weakness that soon became an insecurity and lack of confidence. I was becoming like so many other once-extreme Bozeman athletes whose lives became consumed with work and family. I’d become a weekend warrior—and I didn’t like it.

Stepping Out

A few years ago, I trained hard for the Ridge Run and finished strong. But after two days I felt empty again—I needed a real challenge. The next week, while driving through the Tetons, the Grand loomed large on the horizon. I decided to climb it the next day, sleeping at the trailhead to get an early start. In the morning, I impulsively left most of my gear behind and decided to speed-climb to the top. I took a water bottle and a helmet and ran to the upper saddle, where the technical climbs begin. From there I made the conscious decision to take on the Upper Exum Route, a multi-pitch climb—solo, sans ropes, where a fall could mean death or at least serious injury. These are decisive moments of commitment where risks are measured against potential gain. And the fact is, there is no reasonable justification for this type of risk exposure.

But this was not about being reasonable, it was about self-discovery and growth. About regaining something I’d lost. Something I wanted back.

With sweaty palms, stomach in knots, almost dizzy, I climbed with nothing but my own will to protect me. I moved quickly and deliberately and did not stop or look down until the top. Other climbers looked shocked as I crested the summit without a harness. My heart racing, I looked down to where my car was parked 7,000 feet below and felt more alive and fulfilled than I had for a long time. I returned to my car knowing I had met the challenge of speed, endurance, and self-reliance. I had faced very real fears; I’d believed in myself enough to step out off the ledge and experience the truest form of existing in the moment where nothing else matters but the seamless harmony of body, mind, and soul. This was, for me, the forward movement in my life that I had longed for.

And now at 52 years old I was feeling it again. I had been sitting on the ledge too long. It was time to step off—into the wild unpredictability of an Alaskan winter.

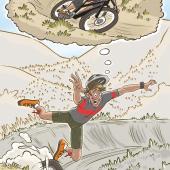

A training ride in Hyalite.

A training ride in Hyalite.

Training Wheels

As fall crept toward winter, the reality of committing to the ITI began to sink in. Temps dropped into the -20s and my 5am fatbike commute across Bozeman started feeling a lot like riding across Alaska in the darkness. Arriving at work after only nine miles, sufficiently frozen, I wondered if I could handle 350 miles in sustained cold. And my employees wondered if I’d finally cracked.

I’d occasionally see the blinking lights of other fatbike commuters. We’d feebly nod as we passed each other; I felt less lonely—less crazy—knowing there were other winter-biking masochists out there. But I had to hone my gear and learn to embrace the only real companion I’d have for two weeks: the cold. I found myself waking up at 3am, anxious, almost panicked, thinking about the vast, frigid Alaskan darkness I would be traveling through alone with only what I had on my bike. Would I survive? Would I be able to hold it together when the cold overtook me, broke me down, leaving me alone and helpless in a merciless, frozen world?

The ice highway through Hell's Gate.

The ice highway through Hell's Gate.

In the morning I’d gear up in the garage for my commute, dreading the opening of the door and the painful blast of sub-zero air as I rode out into the faint light of the new day. Like the cold itself, these inner demons had to be faced head-on, conquered, and left behind. To conquer something you have to immerse yourself in it, understand it, make it your own—and then the fear becomes peace. Time spent living with the cold developed an understanding and respect, where I knew my place and how I could survive in it. We were becoming friends.

Long weekend rides took me out the backroads of Springhill into the night and up Flathead Pass, post-holing to my knees, bivying for four hours, and riding back through Bridger Canyon in the early-morning darkness. Ranchers passed by, shaking their heads and looking at me as if to say, “Transplant.” Fair enough. Concerned passersby often stopped to ask me if I needed a ride. One night in a whiteout blizzard, I shouted down a commuter’s offer: “Yes, I do want to ride in blinding conditions on busy roads with no shoulder in the dark!” Moments like that made me wonder about myself, but I also felt fortunate to live in Bozeman where the terrain and conditions can approximate Alaska without pretending.

The Longest Night

Back in Alaska, I’m freezing my ass off and smiling, six hours into Ptarmigan Pass. Martijn and I have stopped to absorb the sunrise—literally—and I feel like I’ve accomplished great things by surviving the night. We rode through Hell’s Gate (aptly named, if Hell truly froze over) into the checkpoint at Rohn after 75 miles and 18 hours in the -40s. From the condensation of my own breath, my clothes were frozen like a shield from my facemask to my knees.

Frozen drop bags, Rohn checkpoint.

Frozen drop bags, Rohn checkpoint.

The checkpoint was a canvas tent with a wood stove, with temps inside barely hitting -15. Racers were jammed inside lying on pine boughs, trying to warm themselves. Martijn and I found a spot and started the long thaw, replenishing the 15,000 calories we’d burned with frozen protein bars and lukewarm soup. The checkpoint commandant announced that when new riders arrived, we’d have to rotate outside to either bivy in the snow or continue on.

At 11pm it was my turn; I dragged my sleeping bag outside and climbed in. Waking before sunrise, my clothes soaking wet, I decided to move on. I frantically packed my gear to continue before I iced over, but my bike had other plans. Changing a flat tire at 40-below can almost bring a man to (frozen) tears. After days of that kind of cold, a person can become a tad fragile, even irrational. Such a task, basic under normal conditions, becomes insurmountable—a deal-breaker—until you realize it’s simply a matter of survival and is necessary to move forward. Perspective is guided by options. When you don’t have any, it’s pretty simple. Changing a tire in such conditions thus feels like a glorious achievement—especially when it’s finished and you’re making progress once again.

A man and his steed.

A man and his steed.

Challenge Accepted

I don’t know if doing the ITI sounds crazy or inspiring, but it is definitely one thing: it is more. It is more than finishing a “hard” race, and it is more than devoting one day every few weekends to an event or familiar goal. A friend summed it up perfectly a month before the race: “Being out on the trails at -50 is a lot like skiing in the no-fall zone. You absolutely cannot slip up, but the hyper-focus you get to experience is amazing.”

You might not need to push yourself into the no-fall zone to feel a similar more. Bumping up from routine 10k races to your first marathon, leaving the blues behind and tackling black-diamond runs, or plunging into tumultuous whitewater instead of the usual leisurely float—maybe that’s your more. We all have a challenge in our minds that we’ve put off, written off, or slacked off. But I’m here to tell you that these challenges are exactly what we need to grow, to push past our existing boundaries and continue moving forward.

With that in mind, I’ve already signed up for the 2018 ITI. Let the night terrors begin.

The ITI start, Knik, AK.

The ITI start, Knik, AK.

Jeff Brandner is a local businessman, artist, and endurance athlete. More history and ITI details can be found at iditarodtrailinvitational.com.