Divide, Then Conquer

A lesson in patience on the CDT.

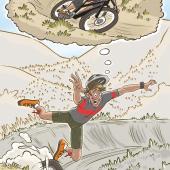

“I think we have to turn around.” My riding partner’s voice drifts to me through the darkness, enveloping us during the thirteenth hour of the second day of our 100-mile mountain-bike ride along the spine of the Rocky Mountains. It’s not what I want to hear, but I’m glad he says it first. We have ten miles to go and we’re post-holing through thigh-deep snowdrifts along a forested ridge that feels like it will never end. We’re pushing fully-loaded bikes while carrying fully-loaded packs, and wherever our headlamps shine we only see more snow. He’s right—we have to get out of here.

The idea itself had been a simple one: kick off summer with a three-day bikepack along some of the finest singletrack Montana has to offer. While the pace wouldn’t be leisurely, one hundred miles in three full days of riding seemed feasible, albeit challenging. But that was the point: to get up in the mountains and try something new. We weren’t hoping for a story to tell. Besides, if a friend asked you to join in on an exciting outdoor adventure, you’d say yes, right? Well, that’s exactly what I did, and I’m not sure it was the right answer.

Our trip starts from Thompson Park on the west side of Pipestone Pass, southeast of Butte. At the Sagebrush Flats trailhead, we gather last-minute items while polishing off Wheat Montana breakfast burritos.

Bikes and bodies weighted down with gear and nourishment, we hit the trail, encountering our first sustained climb right out of the gate. We slog through the first few miles, adjusting rigs for optimal weight distribution. The trail quality along this section of the Continental Divide Trail (CDT) is fantastic. Granite rock, eroded by wind and water, has crumbled into a fine gravel that tires love and riders love even more. With heavy loads, we bob and weave through the trees, smiling ear to ear at the bottom of every descent. The climbs are hard but rideable and we’re making good time. At one point, we break out of the woods and are treated to expansive views of the snow-covered Highland Mountains. We think nothing of the snow, a lapse in judgment that would define our trip.

Snow: a harbinger of things to come

By late afternoon, we’ve covered a lot of ground. It’s at this point that things grind to a halt. It was a low-snow year around Bozeman in 2016, so our assumption was that the same would be true for these mountains. But on Memorial Day Weekend, the drifts are knee-deep. Riding with three days worth of gear is manageable once you get used to it; pushing a bike loaded with gear through snow is challenging, physically and mentally. But this is day one, so we view it as a minor setback with no long-lasting effect on the trip. Well before sundown, we make camp, eat dinner, share some whiskey, and turn in.

We rise with the sun the next morning. Our effort the day before means we slept well, and it’s too early in the trip to be sore or tired. Instant coffee and instant oatmeal serves as breakfast and we’re off. The trail quality is again primo and the morning flies by—until we reach Homestake Pass and a long dirt-road climb to Delmoe Lake. Before committing to this route, we discuss whether to take singletrack that roughly parallels the road. It’s the same trail we plan on riding out the following morning, so we opt for the road. This turns out to be a mistake.

Delmoe Lake and the public land surrounding it is a motorized recreationist’s wet dream. There are miles of double-track, accessible to ATVs, dirt bikes, off-road vehicles, and any other wheeled apparatus willing to take a chance—case in point, we encounter a stock Tacoma hauling down a rock garden we have to push up. Instead of smooth, motorized-free singletrack, we find ourselves grinding up loose, eroded trenches. The going is slow and labored.

But not as slow and labored as it becomes once we reach snowline. It’s at this point that we’re no longer riding bikes, but rather pushing them through snow, carrying them over downed trees, and dragging them up rock gardens. It’s one-foot-in-front-of-the-other kind of progress.

Fast forward to figure-less voices in the dark. After hours of post-holing, we know the only decision is to turn around and bail. Even if we get to the day’s goal, we’ll be camping on a snow-covered ridgeline without the proper gear. The night would be miserable and we know it. The walk out is going to be miserable as well, but odds are we’ll find dry ground to sleep on. We backtrack to a junction with a trail sign. There’s a trailhead denoted, so we figure the trail goes down, which is good. Unable to ride our bikes in the dark, we walk out.

At 1:30am, we stumble into the trailhead parking lot. We haven’t eaten since lunch, so I break out my knife and start slicing summer sausage. I hoover it down while setting up my tent. Hunger and fatigue trump caution and I bring the sausage with me to bed, holding my knife in one hand and bear spray in the other as I pass out.

In the morning, we quietly make breakfast and drink coffee, realizing there’s no sense in attempting to complete our route as planned. Instead, we bike out along a dirt Forest Service road, then hook up with I-15 south into Butte. Semis whine along the interstate, their choked groans reinforcing our failure. While slogging through snowdrifts is physically challenging, it takes a special kind of focus to keep pedaling when 40-ton trucks fly by at 80 miles an hour.

Failing to complete the 100-mile loop was disappointing, but sometimes patience is rewarded. Later that summer, we went back to the Homestake Pass trailhead. This time, instead of climbing the dirt road to Delmoe, we went left and rode the CDT singletrack back to the junction where we bailed. The natural flow of the trail, the complete solitude of the landscape, and the satisfaction of completing our route… the experience perfectly bookended the summer riding season. The celebration we’d planned for Memorial Day was not lost, only delayed until just after Labor Day. In hindsight, I guess I’m glad I said yes.