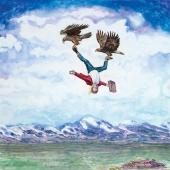

Fear Knot

Learning to accept uncertainty.

“When nothing is sure, everything is possible.”—Margaret Drabble

The stone was cool and slightly clammy with morning dew as the canyon warmed beneath a molten midsummer sunrise. Gear—cams and draws and carabiners—clinked happily on my harness while my partner silently flaked out rope on a flat rock. I sipped coffee from a dented thermos and looked up.

A narrow finger crack lilted up the cliff to a bulge, where it—and the rest of the climb—disappeared from view. I didn’t know much about the climb except that it was loosely rated near the terminus of my ability, and at least three pitches long: at least 450 vertical feet of unknown holds, protection, and belays. I’d been thinking about it all night, lying in the bed of my truck at the trailhead, drunk on nervous excitement, what-ifs ricocheting between my ears like rockfall.

This morning, however, a familiar sensation tickled my spine. Fear, anticipation, adrenaline: uncertainty. Standing at the base of the cliff, the what-ifs ceased to matter. I didn’t know what I would find, but I knew I would find it.

For outdoorspeople in southwest Montana, uncertainty is a constant companion—we embrace it as a community rule. Unpredictable weather, wild animals (some of which reside above us on the food chain), unforgiving geography, sheer remoteness—controlling all of the variables is impossible, and so each of us, when we set off into the hills, accept a certain amount of uncertainty. That’s why we call it adventure. With some of the things we do—like climbing—the entire point is to embrace the unknown. And I like to think it makes us better, stronger people.

Many (maybe even most) people and communities spend considerable time, money, and energy trying to reduce uncertainty. I grew up in the Midwest, where things like rock climbing are largely considered “dumbass.” Going crappie fishing is about as unpredictable as many folks can tolerate, and at least anecdotally, the goal of any life should be to achieve supreme security.

In fact, it’s been suggested that in the U.S. there’s an institutional fear of the unknown—clearly evidenced by the ongoing opposition to renewable energy, the arguments against wolf and grizzly-bear hunting, and the various debates over public-land ownership and climate change. We, by our human nature, try to control variables that by nature’s nature, cannot be controlled. But if we accept (if not embrace) uncertainty, and practice strategies for dealing with our own anxiety—which is ultimately the problem— things become far less scary. Here in Montana, by simple necessity, we practice these strategies every time we go for a hike, paddle, hunt, or climb. It’s a pioneer ethos of which I’m proud, and from which I’ve taken much—not just as an outdoorsman, but also as a husband, business owner, and community member.

With one more long look, I tied into the rope, high-fived my partner, and stepped onto the wall. I didn’t know where I was going, what it would look like, or what would happen. But that was okay. I’d figure it out—which of course, was the entire point.