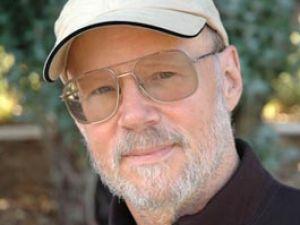

Tim Cahill, Mishap Maestro

Tim Cahill's amazing stories of misadventure.

So there you are, buzzing across northern Mali, looking for the legendary salt mines of the Sahara. Mali is a bit unstable these days – the Tuareg people of the North are rebelling against the dominant black government in the south – and so you’ve brought along some hired muscle. You look back, and notice that you’re being followed by a bunch of Tuareg warlords in a stolen UN LandCruiser. Your bodyguard takes one look at them and bolts. It’s getting dark, you and your fellow pale-skinned travelers stand out like Marilyn Manson at Sunday School, and you’re on your own in revolt-ridden West Africa.

What to do? If you’re Tim Cahill, world-traveler, acclaimed outdoor writer, and longtime Livingston local, turning back is not an option. "What we did was approach these guys on the street, in public, and say ‘would you guys like to be our bodyguards? We’ll pay you for it.’" The trick was just bold enough to work, and the group, now warlord-strong, resumed its journey northward.

When they reached the mines a fierce sandstorm whipped up, and after it was over one of their party was missing. Guessing that he’d been kidnapped by the Arab mine-owners, Cahill and his friends offered ransom. But the Arabs denied any involvement. "We found him the next day," remembers Cahill. "He’d gotten lost in the storm. He was about ten miles away, holed up in an old French Foreign Legion fort, hiding from the Arabs."

"Now there’s an ideal mishap," says Cahill. "It’s got politics, revolution, people lost in the sand" – in other words, something to write about. For therein lies the secret to Cahill’s award-winning travel writing: something has to go wrong. And for the tall, thick-bearded, interminably affable author of six books and over 300 articles, something usually does.

Pecked to Death by Ducks, Jaguars Ripped My Flesh, A Wolverine is Eating My Leg – these are the kinds of wild book titles that reflect Cahill’s unique brand of misadventure. It seems that wherever he goes, calamity follows: he’s contracted malaria in New Guinea, been lost at sea in the Philippines, fallen off cliffs in British Columbia, and faced charging gorillas in Rwanda. He’s flown with drunken pilots in Venezuela and been detained by battery-obsessed authorities in Honduras. Once, on a trip to England, Cahill found himself being interrogated by local police about The Dangerous Sports Club, a tuxedo-clad, champagne-drinking troop of thrill-seekers – to which Cahill admits no affiliation – who hurled themselves off of a bridge in Bristol and made a not-so-sneaky getaway in awaiting powerboats.

Just how does Cahill get himself into these bizarre and often life-threatening situations? "A lot of it has to do with being fairly incompetent," he explains in his characteristically dry manner. "I’ve gotten lost a half-mile from camp." It’s this kind of self-mocking humor, combined with a sort of playful irreverence, that informs most of Cahill’s writing, and much of his life in general.

Tim Cahill’s peril-laden vocation originated like most of his adventures – by accident. It was the late 1960s, and Cahill was a small-town Wisconsin boy studying for a Master’s degree in Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. A photographer friend needed some text to accompany his submissions, and so he asked Cahill to write an article about birds. Though "afflicted with ornithological dyslexia," Cahill managed to think of one bird that sparked his interest: the turkey vulture. "Those things are cool," he remembers thinking, "I could write something about them." His research consisted of climbing a hill above the city, lying down and playing dead, and waiting for the vultures to circle above him – "personally-engineered bird-watching," he calls it. However unorthodox the method, it worked: the article made the San Francisco Examiner, and the editor liked it so much he asked Cahill for more of his work.

Things moved fast from there; within a year he was hired on at what was then a fledgling Rolling Stone Magazine. It was 1970, and for the next seven years Cahill would work, and party, with some of the most notable writers of his generation: Hunter S. Thompson, Tim Farris, and David Felton, among others. "That was the golden age of Rolling Stone," Cahill remembers. "Books have been written about it. It was sex, drugs, and rock & roll. Most of us were young, and it was hippie-dippy days in San Francisco. There were no moral restrictions – for that matter, there were no restrictions of any kind. The only thing that prevented it from becoming an all-out party was that we worked 16-hour days."

When Rolling Stone moved to New York, Cahill stayed in San Francisco and became a founding editor of Outside Magazine, a then-unique publication that would help spawn an entire genre of magazine writing – literate, well-informed outdoor journalism. Cahill convinced the publisher that an international adventure column would find a hungry audience, and he began to get assignments to remote locales around the world. His life of misadventure had begun.

Since then, he’s survived kayaking with orcas, diving with sharks, swimming in the Arctic Ocean, and peeping on copulating gorillas. He’s camped on every continent, including Antarctica. He’s floated remote rivers in India and New Guinea and been lost in the jungles of South America. He’s flown into the eye of a hurricane and to the rim of an erupting volcano in Ecuador. He has also been ruthlessly taunted – for his large, disheveled gringo appearance – by natives in Siberia, India, and in the Congo. The children in one particular Honduran village refer to him as Senor Wazoo.

Just as prepensely bohemian in his professional life, Cahill is a journalistic maverick who bucked convention and became a work-at-home freelance writer when such an idea was unheard of. "I kind of figured things out way before everyone else did," he remembers. Back in the late 70s, when Outside transferred its offices to Chicago, Cahill faced two choices: move with Outside to Chicago, or go to New York with Rolling Stone. Thinking it over, he had a sudden revelation: "‘Wait a second,’ I thought, ‘as a writer, I don’t have to work in an office, I don’t have to be in the city. I can be exactly where I want to be.’" That place was Livingston, Montana – a town he fell in love with after a few visits to see early Outside contributors Tom McGuane and Russell Chatham.

Cahill’s then-revolutionary little plan worked – over the next two decades he would write, full-time, for dozens of national magazines, including National Geographic, Life, Travel and Leisure, Reader’s Digest, Esquire, and The New York Times Book Review – all from his little house in southwestern Montana. He wrote books, too: Buried Dreams, his true-crime account of the serial killer John Wayne Gacy, Jr., was a national best-seller. He also gave numerous speeches – an activity which he once did for free, but which soon began to demand way too much of his time. So he found a way to keep speaking to a comfortable minimum: "I started to charge a great deal of money," he explains, "and the invitations dropped off precipitously." In the past few years, Cahill has taught writing seminars, and most recently, has taken up screenwriting – an endeavor for which he had a natural and immediate talent: his first screenplay was for the immensely popular IMAX film Everest. Cahill’s cinematic debut went on to become one of the top 20 films of the year, besting Titanic in per-screen ticket sales. Another of his screenplays, the documentary film The Living Sea, was nominated for an Academy Award.

But even such promising (not to mention profitable) screenwriting success can’t keep Cahill out of the field. At 56, he’s still a hazard-hungry gadabout, scuba diving, trekking, kayaking, and caving – and suffering, quite happily, all kinds of touch-and-go mishaps. "I have the best job in American journalism," he insists, smiling and reclining on his sofa in Livingston. The house abounds with testaments to a thirty-year career of all-expense-paid travel to remote and often dangerous places: a primitive bow and arrow set from Irian Jaya, in New Guinea; an Indonesian penis gourd; ornate clay pots from the jungles of Mexico; and hordes of graven images from native cultures the world over.

There are other signs, too: a framed magazine cover of him making what was then the longest fixed-rope climb ever, a ten-hour ascent of Half Dome in Yosemite (20 years later, the climb still ranks number two; his climbing partners beat their own record a few years later on Canada’s Baffin Island). Gracing the dining room wall is a Guinness Book World Record for the fastest Pan-American traverse. He and his driving partner drove a stock GMC truck from Tierra Del Fuego to Prudhoe Bay in Alaska in a scant twenty-three days, beating the previous record by a matter of weeks. Cahill documented the adventure in his third book, Road Fever.

The only thing that’s changed for Cahill these days is his range of destinations. "Nowadays, I pretty much travel only to politically-unstable countries," he says. In his search for remote, obscure, dangerous locales, he explains, "those are the only places left." But is Cahill worried about people reading his articles and tramping off to these far-away places, thereby ruining their pristine, remote status? Not a bit. "I’m not really certain that a whole bunch of people go where I go," he says with a grin. "I mean, how many people really want to spend weeks in the Sahara, in 125 degree heat, worrying about Tuareg warlords and Arab kidnappers?"

This article is adapted from one printed in The Tributary Magazine, a now-defunct, alternative newspaper dedicated to the lifestyle and culture of southwest Montana.