Cerebral Skiing

If it's more physical than mental, you're doing it wrong.

By the time spring skiing wraps up, my mind’s wires fray and spark like a busted robot; I can no longer tolerate the haunting nightmares of being eviscerated by a tree’s gnarled branches or suffocating in a white tomb. I used to get excited to go skiing—now, I wake up and feel the sting of the blood in my fingers crystalizing and thawing for the thousandth time; I feel the wind-driven snow chipping away at my face. I think of the season’s runs that I have yet to check off my list: usually tight chutes with a mandatory avalanche potential. I think all this and shrink back under my covers until my clammy hand reaches out from the pile of covers and dials the Bridger Bowl snow phone. Six inches and counting… damn! I have to go skiing.

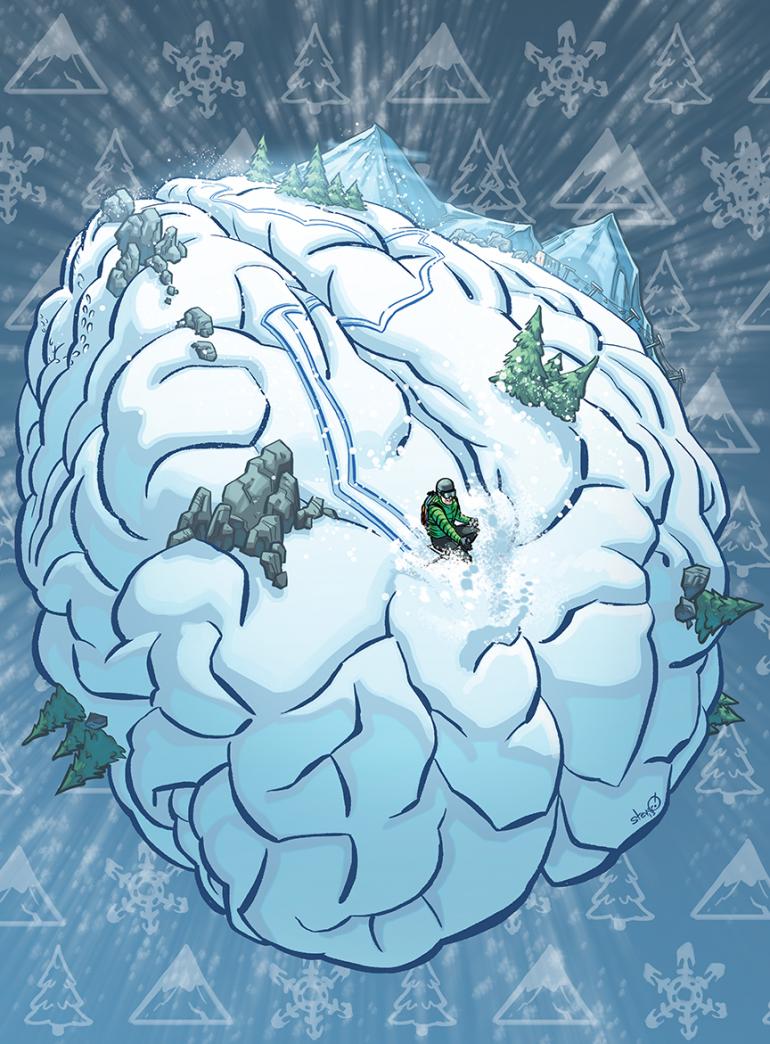

Humans have the burden of controlling our instincts—and in the case of skiing, the ability to ignore them. Yet we also have the ability to sharpen our senses. This is what I refer to as “cerebral skiing.” Not only does skiing teach us how to quiet our minds during the run, but the approach also teaches us to sharpen them. I observe two types of cerebral activity necessary to survive in backcountry skiing: there is the passive acceptance of nature’s mastery over the perceived “self,” and there are the active calculations that use every possible factor to minimize danger.

Still in bed, I read the avy report: moderate. Guess I can’t write it off as a resort day. The tension builds in my mind. I bet “Poseidon” is filled in now; I better check it out since I was bragging on it at the bar last night. I make my way to the mountain, going through the motions. I have the will to keep at it day after year, but the excitement of carving a classy S on an untracked face, or flawlessly skiing a technical run gets obscured by foreboding thoughts. I’m already calculating before I get to the resort: which direction did the wind blow last night and which way now? Should I wear my knee sleeves and spine protector? Which skis are best for these conditions? As I approach the mountain I look at any visible peak: any fresh slides? Wind loading? What aspects look the best? I nearly crash my car squinting at the snowy summits.

There comes a point where age and skill level gets high enough that any attempt at a personal best becomes a matter of serious consequences… unless you have a team of avalanche-control experts and a helicopter with you. Most of us don’t have wide-open pillow lines, spines, and clear landings in our backyard; we must make do, and often this adds to the danger. The wilderness can be a lonely place. Our tracks appear like sand mandalas: impermanent. Backcountry skiers tend to be comfortable with this notion of impermanence. I don’t think I would ever go backcountry skiing if I wasn’t attenuated to the idea that I might never make it back. But there is no sense in being reckless, and being buried alive is probably the worst death I could imagine. So I worry.

I get to the mountain. With six inches and counting, I probably won’t go into the backcountry. There is plenty of time for that in the next few days, so I head to the resort. That’s wise decision number one. Yet, even with six inches I won’t actually ski the resort; after spending 20 years on the East Coast, I refuse to ski over another person’s tracks: it’s vulgar. I will go out of bounds.

While riding the chair I look at the Ridge to see how filled-in my favorite chutes look—the ones that aren’t even skiable most years. Should I go up the Ridge and over, or should I go out the gate and skin up to the zone? The angel on one shoulder says: you can dig a pit and get a firsthand look at the snowpack if you go out the gate. The demon on my other says: you know the snowpack; you’ve been skiing it all season, twice already this week… plus, you can avoid the avalanche danger on the skin up if you skip it, drop in, and get the hell out of there with as few turns as possible. I wonder if skiers realize how many good and bad decisions are made before they even get to the approach.

The approach marks the place where the real calculations begin. How does this snow feel under my feet? I knock snow off branches to see if it sticks. My pole hits a layer of hard snow about a foot down, then soft, then hard again… distressing. I listen: does it sound normal or creaky? It doesn’t squeak—it’s quiet. Can I hear anyone else? Am I alone out here? The snowfall looks consistent; there are no little patterns on the surface that reveal severe wind or temperature drop; no convex mounds in erratic places. I think about what I want to ski on my list. Poseidon.

The last time I skied this run was with the only other skier I know in the area who likes to push his limits. The hike out to the sidecountry from the resort takes an hour: neither of us spoke a word the entire hike. When I asked him later he said he was worried about the mandatory cliff. I said I was worried about the avalanche potential.

I’ve decided to ski it. I waited to make the decision until I was nearly on top of the line, but my subconscious made this decision as soon as I dialed the snow phone. Shit, I’m getting tired. Usually when I get fatigued, I just think about the run. Just dip into the trees immediately, stay as tight as possible until you get to the hanging snowfield. Ski fast as hell. Try not to carve a turn here, but in case you do, make sure it’s above the two big pine trees so you don’t get washed into the chute and off the cliff. Stop here for a split second to make sure you’re safe. Find the entrance, don’t stop—you’re committed. Ride the spine—if it’s filled in enough—to keep off the slide path. Otherwise, scurry down the chute; don’t jump-turn if you can help it, lightly slide down. As soon as you see the pinch, straight-line it. Once out of the pinch make two or three turns to slow speed as you make it to the cliff. Aim for any part that doesn’t have a lot of shwack. Get your knees up, stomp the landing and ski away. If you fall, get the hell out of there before the mountain comes down on top of you. By the time I reach the end of my approach, I have skied the run five times in my head.

On top of the run, I feel nauseated; I have been burping most of the hike. I don’t eat much before a day like this, and I have no appetite until the danger is in my rearview mirror. Go through the motions. I hate gearing up, but I do my best to get it done quickly. After a nervous pee, I tuck away my skins and I make sure I’ve taken my boots out of walk mode. Once my skis are on, things feel better—they turn me into a mountain goat. Last, I take a gander beneath me for any signs of avalanche danger: wind crust, cornices—or worst of all, someone else’s tracks. Don’t worry, you are the only person who ever skis this bitch; it doesn’t even have a name (I call it “Poseidon” because sometimes the snow runs through it like water). I turn my helmet camera on to record my possible demise for posterity, whack a cornice for McConkey, take a few deep breaths and drop in. Save me.

The rest takes care of itself. If this was a normal powder run, I would be elated. A run like this, I’m puckered, but second-guessing your skills at this point is like telling the mob you were just there for an internship.

When I make it to the bottom of such runs without leaving my gear, a few teeth, and part of my soul on the mountain, I can’t help but yelp. You think all that worry isn’t worth it? In those first few seconds of safety, all trepidation washes away. It often sends me right back up the hill for another run. I wonder many times I have bellowed “Glory be!” only to have some random skier tour by with a smirk (but he saw my track, so he can go to hell).

It’s time for a well-earned beer. I spend the rest of the day and into the night jazzed on skiing again, and all I can talk about is the next run on my list and getting out again tomorrow. Then the alarm rings and the first thing to enter my waking mind is fear.

I’m not an avalanche or backcountry expert. I’m a skier who uses everything in my physical and mental arsenal to push my limits—while making it home to do it again another day. Some may think that I fail to consider certain safety elements, or perhaps you have strict rules about skiing alone or not going during a storm. I don’t mind admitting my faults in order in order to facilitate an honest dialogue. For me, the only way to gain experience is to get out of one’s element now and again. Survival can’t always be a matter of dogmatically following another’s advice, but a matter of reinforcing wise decision-making strategies through repetition and the facing of new problems.

As ski season ramps up and grandiose ideas congeal in our minds for the upcoming season, it doesn’t hurt to remind ourselves—even now in the safety of the off-season—that putting all those ideas of ours into practice is no mere fantasy. If skiing is as cerebral as I understand it to be, then the ski season is endless, after all.