Soon

Waiting out winter.

Autumn ended in December, and with it came that same old wash of emotion that has followed you like a lonesome dog almost all of your life: melancholy. Hunting season is over.

This one ended on a patch of limestone and cheatgrass. It ended with the final bark from the 20-gauge over/under, a hurried, swingless poke at a zipping Hungarian partridge. A miss. You don’t want to end on a miss. It would have been much sweeter to see the bird jump and watch it in slow motion. They say Ted Williams could see the stitching on baseballs hurled his way as he swung that big bat, and sometimes, you see birds that way, all details, individual feathers, that bandit partridge mask, the shotgun coming to the shoulder, pulling the trigger in one smooth stroke that you don’t even feel. This wasn’t one of those occasions, and you knew you had missed even before the gun came to your shoulder.

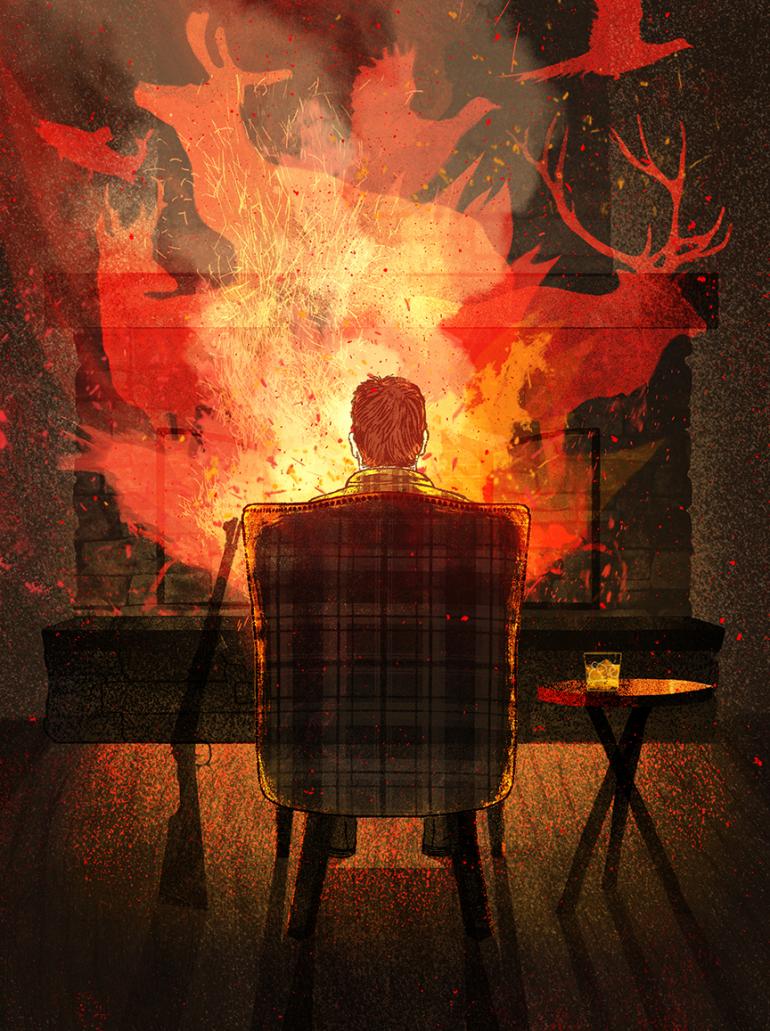

But the last bird jumped and you missed and then the sun was dipping over the far rim and you were thinking of barrel-aged whiskey poured over ice chips and a good cigar smoked by a sage fire. The high-mountain winter slipped through your wool shirt and chilled the sweat at the base of your spine and you shouldered your gun, called the dog to heel, and headed down the thin, hard ridge to the valley below and the truck there. And there is that sadness on your shoulder, a familiar old friend. It’s over. Last hunt. It’s over.

Your sporting life is marked by the tide of seasons. Autumn parallels the hunt, starting in late August when you crawl through the sage pushing your bow before you, stalking speed goats. Fall days are defined by Absaroka spruce and bugling bull elk, by the sun dipping down over the Gravellies while you bend to the knifework on a cow elk, by pheasants bursting from a mad tangle of wild rose, by a damned good mountain horse beneath you sure and true on a twisting mountain trail. You go trout hunting too, and you cast drowned hoppers between boats of cottonwood leaves and occasionally pin the tough-toothed jaw of a big brown on the spawn, fighting hard against bent graphite and stretched plastic, splashing to net and let go into near-icewater. The hunt continues, in the good years, until the first January—Hungarian partridge, sharptail grouse, a late elk hunt. Some years, life takes over your passion and swallows it, and your autumn ends too soon, in the frozen cattails of a Montana December where big greenheads paddle among the bergs.

And so, Winter. It stretches out before you and there’s a cold wind carrying snow out of the north, and even south. There is no promise of anything much at all except whiteness and chill. There’s a woodstove and a huge pile of Doug fir and pine stacked against the side of the house and hay in the barn and meat in the freezer. Nothing to do but wait it out.

So you pull old books off the shelf and page through, smelling the mustiness of time, feeling the leather bindings in your hands, and dancing your eye across the pages. Here you travel up desert ridges, ride wild rivers, feel shale beneath your boots in high-mountain holds, and you dream. Sometimes, you think of going out into the shrill wind. You could shoot rabbits, but then you reflect on the feather and fin and fur of the past year and you think: that was enough. That was enough. When the books are marked and closed, the scent of gun oil and solvent hits your nostrils, and you feel that sadness again when you wipe a thin coat of oil on the barrel of that good rifle that shot so true not so long ago. You put that rifle back in its place, knowing you will not touch it for some time, and you clean your knives and repair that hole in the pannier caused by a young first-time packhorse not familiar with his new width on a narrow trail.

One night, as the wind pushes sheets of snow against the north wall and the old Round Oak wood stove crackles with butter-yellow ponderosa, something happens. You reach the end of a sentence and you stop. You put down that good book, carefully marking the page, and you stand. From the hearth, the cat and the setters eye you: something is up with the boss.

The lonesome dog is gone. In its place is a happy pup, a healthy chunk of excitement full of eagerness and anticipation. You walk to the back bedroom where the fly vise has been gripped on the tying bench, untouched for a whole summer and autumn. You sit down. You dig out a No. 4 hook, and scratch around for material. And you start to tie. A big fly. Big enough for a big fish.

You have kept materials from the harvest season—materials from animals and birds you shot. Patches of elk hair for elk hair caddis. Skins of partridge for soft hackles. The neck of a grizzly-hackled rooster that a friend’s black Lab chased down and strangled to death in his own barnyard.

Hey, can I have that rooster’s skin? Unless you tie, it’s an odd request, indeed. But the fruits of harvest and mishap are all laid out before you now, salted and seasoned to be spun onto hook and tied with colorful thread. You are not an expert by any means—tying parachutes is begging frustration—but as snow blasts against the west window, you sit warm and sip Kentucky whiskey and tie flies for the coming year.

There is something poetic and right and good about sitting at a fly vise using feathers from birds that brought you so much enjoyment months earlier, hair from the hide of an elk you shot cleanly and thanked for giving her life so you could enjoy elk steak broiled on an outdoor grill. It feels good, to use the animal and the bird like this, to eat a good meal of it, and to use its body to catch fish. There is self-sufficiency in it, like growing a compost pile and a good garden coming strong in the spring; like picking chokecherries for jam and syrup in the fall; like burning wood to heat the house. The days and weeks filter by quickly now, gone is that sad dog.

One night, the book goes unopened and the vise unused. You look at maps. You dream of pack trips into large country, of mountain lakes with big Yellowstone cutts swimming strong and selectively through clear water. You look at blue lines on maps, country you haven’t seen yet and have threatened to hike into for years. You’ll go this summer. The next week, you pull out a calendar and stroke the pen across days, weeks. And there’s a whole spring ahead, too.

Soon, you think, you will be camping beneath fragrant ponderosa and painting chalk across the tongue of the call, then working the lost yelp for that big gobbler you saw two nights before. Soon you will be riding horseback over open sage where the antlers of the previous autumn have fallen, smelling those damned fine fragrances of leather and horse and sweet sage. Soon you will be at the oars, carefully stroking backwater just slow enough so that your friend can cast that big fly you just tied to the place where that big brown has stuck its mouth up like a catcher’s mitt. Soon.